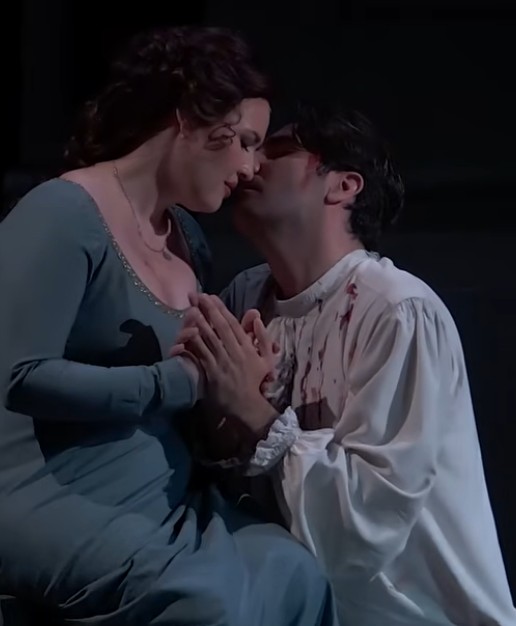

Above: Emma Grimsley and Matt Dengler in Heartbeat Opera’s MANON! Photo by Andrew Boyle.

~ Author: Mark Anthony Martinez II

What a treat! Heartbeat Opera’s translation and re-envisioning of the classic Massenet opera MANON brought a breath of fresh air and timeless relevancy to this classic staple.

Heartbeat Opera is known for their innovative performances. Setting TOSCA in Iran, bringing to the forefront the homosexual subtext that exists within Tchaikovsky’s EUGENE ONEGIN, and in this performance staging Manon more like a musical theatre piece than an opera.

Re-envisioning classic opera is at times a controversial take. I personally think that as long as the piece makes sense and has a point, I’m all for new imaginings. I will say that when I first saw that MANON would be done in a more musical theater style, with amplification, I wondered if this was a good choice or just done in order to be “different.” But the more I thought about it, Massenet’s Manon is really similar to a musical. The famous tunes like “En Fermant Les Yeux” aren’t typical bombastic arias, and if anything are closer in style to sweet ballads you might hear on Broadway now. So I went in with an open mind.

Before going into any more detail, I’ll say this: the opening night performance of MANON! was fantastic, moving, beautiful, and so well staged. It was perhaps one of my favorite stagings and performances of an opera I’d seen in a long while, and it was truly an intelligent and worthwhile adaptation. Not everything was perfect. There was one line I noticed that was fumbled and some pitchy notes, but as a whole work, it was phenomenal.

I think the ultimate litmus test of whether something is successful in creating a show is if a true neophyte can go in and enjoy it. I went to see the show with a friend who hasn’t had much exposure to opera or musicals for that matter, but she loved it. That’s not something that can be said of most productions.

As we entered, audience members were given a letter with a green wax seal bearing the Heartbeat Opera logo. A very cute touch if you know how important letters are to the plot.

The set at the Irondale in Brooklyn was minimal but interesting. The stage initially was draped in a white cloth with chandeliers hanging right above it. Emma Grimsley, who plays Manon, prances out, inspects the stage, and then pulls the cloth away, revealing the stage underneath, and leaves.

The show then starts for real as Kathryn McCreary (Pousette), Natalie Walker (Javotte), and Glen Seven Allen (Guillot) stampede onto the stage for a very lightly veiled night of debauchery and sex.

The audience and I loved these heel characters who so adeptly sang and acted out their roles. They all brought life and comedy to characters who could easily become mere plot devices.

Ms. Walker was the socially intelligent courtesan who did her best to navigate the difficult life of depending on fickle men for her livelihood and safety. She was always funny but had clear direction and motivation for survival. Ms. McCreary was the bawdier of the two and was the one who spoke up for the needs of both herself and her comrade of sorts.

What I loved about this duo was that they had a humanity to them that made them more than plot devices. You could tell they fought for their own survival, but they also cared for the well-being of Manon, a young country girl who was being preyed upon by Guillot.

Guillot was fantastically acted and sung by Glenn Steven Allen. He was a lecherous older man who preyed on weak women, but he had a comedic quality that didn’t make him a blank villain. We never rooted for him, but you knew that when he was on stage it would be an entertaining romp.

The orchestra was behind the stage, which is an added difficulty because the conductor and singers can’t see each other easily, but from the moment the music came in until the end, there was never an issue.

I was wondering if something different would be done with the music since it was a new interpretation of the opera, but besides being a reduced ensemble, the music stayed true to the original.

When Ms. Grimsley made her first real entrance, the plot really got started. What struck me about this production was how well acted it was. Opera is largely a music-first art form, but by treating this as a musical theatre piece, the singers were able to lean into the acting to enhance the drama of the music and plot. For instance, when Jamari Darling (Lescaut) and Ms. Grimsley arrive on stage, you can immediately tell that there is something sinister about their relationship; this sets the plot into motion.

Darling was a scene-stealing actor and a true audience favorite. He brought a sliminess to Lescaut, but in a sort of Disney villain way. You hated him for what he was doing, but he was just so entertaining that you couldn’t help but want him to stay on stage longer. On top of singing and acting, Darling is a phenomenal dancer and brought tastes of the NYC ballroom world to the stage.

Ms. Grimsley truly embodied the character of Manon phenomenally. At times young and naive, but always with the femme fatale lurking underneath. As is the case with most shows when one is the title character, Ms. Grimsley had the monumental task of performing almost nonstop, and she did it with technical perfection and aplomb.

Every note of coloratura was used in service of what Manon was feeling; every musical gesture furthered the plot. Ms. Grimsley really was the star of the show for a reason.

As the plot progressed and Des Grieux came into the fold, the two of them had instant chemistry. Matt Dengler looked and sounded like the naive but loving chevalier. You could tell from the very beginning that the two of them truly felt a special bond, and one couldn’t help but grin when they absconded away with Guillot’s carriage.

Throughout the entire show, what struck me was how true to the material the production was, but also how much the plot was elevated by the adaptation. Things like the genuine sexual chemistry between Manon and Des Grieux that brought about her downfall would normally be lost in florid staging. However, in this adaptation, the more carnal side of their relationship is not hidden or merely alluded to, but shown, all while still being PG-13, in a true-to-life, realistic way. It now actually made sense why Des Grieux would leave the priesthood for Manon, as one example.

Heartbeat Opera’s production of MANON! was truly a wonderful show and a great re-imagining of a classic. I can’t wait to see what their next performance will be.

Note: The run of MANON! has been extended thru February 15th. Details here.

~ Mark Anthony Martinez II