~ Author: Lane Raffaldini Rubin

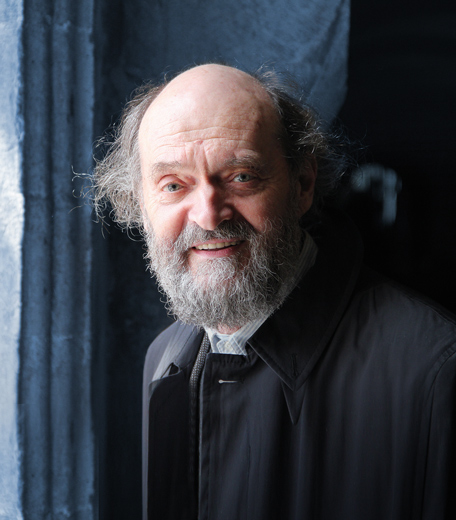

Thursday and Friday October23rd and 24th, 2025 – Why is the music of Arvo Pärt (above) so beloved around the world? Perhaps it has to do with our penchant for metaphor. Pärt’s music, through the richness it creates out of modest ingredients, conjures other—higher—things. Its representational power makes it mystical to some, mysterious to others, and glorious to others still.

Carnegie Hall is celebrating Arvo Pärt’s 90th birthday this season by giving him its annual Debs Composer’s Chair and holding a series of performances featuring his works. It all kicked off on Thursday and Friday with back-to-back all-Pärt programs. In Thursday’s mainstage performance the Estonian Festival Orchestra (led by its founder Paavo Järvi) presented a survey of Pärt’s greatest hits. Friday’s performance, in Zankel Hall, featured the Estonian Philharmonic Chamber Choir and Tallinn Chamber Orchestra in an array of lesser-known works.

The program on Thursday night was comprised of pieces written between 1963 and 2013—a full fifty years—representing the many modes of Pärt’s output, from early twelve-tone writing to the fully formed tintinnabuli style that he invented and became famous for.

The 1977 Cantus in memoriam Benjamin Britten opened the concert with the singular toll of a bell. From silence, the strings slowly grow into a glimmering churn that layers into a thick slab of sound before eventually sifting into pure unison.

Perpetuum Mobile, written in 1963, has an similarly imperceptible start that settles into a patter of staccato syncopated notes in the winds. A ceaseless repetitive rhythm lends this piece perpetual time, if not perpetual motion per se. Rumbling drums undergird a glacial crescendo toward a monumental peak. From there, the music follows its long arc back to nothing, finishing where it began, in silence.

In contrast, La Sindone (The Shroud) of 2005, which opens with aching diminished chords in the strings, seemed melodramatic and overly figured. The texture does thin itself out in later passages and weaves together brief linear threads of notes, but the piece never sheds the unusual quasi-cinematic sound that makes it uncharacteristic of Pärt’s work.

The Estonian Philharmonic Chamber Choir joined the orchestra for the 2009 Adam’s Lament, a setting of a prose text about the desolation and abject grief of Adam. Chantlike introductory statements in the choir grow into glorious major chords, which Pärt—and audiences—savor in inhabiting. Much of this piece is derived from simple stepwise motion built around these tectonic triads.

In works like this, Pärt achieves textures and colors reminiscent of the sacred music of Tallis, Josquin, and other renaissance composers of music for the Church. Pärt permits himself the use of a narrow set of compositional tools, which he deploys with precise control. The result is a varied bounty that belies the severe economy of means of its component parts.

In this way, Pärt offers musical instantiation to Giorgio Agamben’s concept of altissima povertà (“highest poverty”), the ascetic notion often associated with St. Francis of renouncing earthly excess in favor of rule-based forms of life comprising only the most basic elements.

Above: Hans Christian Aavik and Midori playing the Tabula Rasa; photo by Fadi Kheir

The second half of Thursday’s program featured two of Pärt’s best works, Tabula Rasa and Fratres, both written in 1977. The young Estonian violinist Hans Christian Aavik and the veteran star Midori joined the Orchestra as soloists in Tabula Rasa. (Nico Muhly also joined on the prepared piano, seated unceremoniously near the back of the stage)

Midori and Aavik were perfect partners in the intricate interplay of the first movement (Ludus).The kaleidoscopic, fractal sound of the two violins wended between moments of Vivaldian rationality, cosmic splendor, and demonic fiddling.

The second movement is entitled Silentium, the word inscribed on monastic refectory walls to instruct brothers to eat in silence and listen mindfully to the recitation of prayer. Here the music in the orchestra provides a slow temporal fabric above which the violins float in cloudlike, vaporous suspension, passing simple figures between them that act like ribbons of smoke steadily rising from votive tapers.

In Fratres, presented here in its version for strings and percussion—a slightly disappointing fact given that two able violinists were on hand to play the version for violin and orchestra—the music takes as much time and space as it needs to, unfurling its series of changing pitches like necessary steps in a penitential ritual. The piece opens with gossamer high strings shining over a sustained bass ground like the first rays of light in a sunrise.

Compare that to Swansong (2013), a fully leavened, meaty pastorale that Sibelius might have written. Pärt uses the orchestra to paint traditional colors in this piece (including the facile association of the oboe’s sound with the swan), which even swells into a Romantic, cymbal-crashing climax. The result could not be more different from the austere sublimity of Fratres.

Muhly and the Choir returned to the stage for Credo (1968), one of Pärt’s most impressively strange works. Credo features passages of J.S. Bach’s Prelude in C Major from the Well-Tempered Clavier, which are meant to represent elemental “good” in the face of darker forces. They come off, however, as almost juvenile when pitted against Pärt’s mammoth depictions of evil, including passages that evoke Haydn’s “representation of chaos” with ululating screams from the choir.

Järvi acted as a humble, devoted shepherd of the evening’s music, treating his role on the podium not only as timekeeper, but also as manager of coherent timbres across the orchestra and guide through the creeping pace of the broad arcs that span each piece.

Photo above by Jennifer Taylor

On Friday the singers of the Estonian Philharmonic Chamber Choir joined the Tallinn Chamber Orchestra in Zankel Hall for a more intimate set of Pärt’s works. While the orchestral and choral forces were reduced, the evening featured lengthy settings of liturgical texts including Stabat Mater, Magnificat, and Te Deum, as well as L’Abbé Agathon, a French setting of part of the fifth century Sayings of the Desert Fathers.

Pärt’s Magnificat (1989) and Te Deum (1985), which were played together and made up the second half of Friday’s program, were the evening’s highlights. Magnificat begins with women’s voices high up in the metaphorical rafters. This is Pärt’s take on stile antico homophonic writing, in which all the a cappella vocal parts move with the same rhythm.

Te Deum constructs a towering cathedral of sound around this core. Pärt lays out a complex dramatic topography that navigates between sober moments of plainchant, impressively grand crests (as at “Tu Rex gloriae, Christe”), and the rumbling piling-up of tension in between (as at “Fiat misericordia tua”).

The listener enters a kind of trance in Pärt’s music—one that demands patience and rewards it with the glory and richness of simple things. But it is a fragile hypnosis and its precarity was tested time and again on Thursday and Friday nights with the overactive mundanity of squeaky chairs, cellphone chimes, and coughing. In Zankel Hall, the N, Q, R, and W trains run mere feet away from the subterranean stage. Their periodic rumblings were quite distracting at first, but as the Te Deum faded away (“Amen. Sanctus, Sanctus, Sanctus”), the sounds of the subway tethered the ethereal to the terrestrial, the lofty to the earthly, and these rumblings became part of the music too.

~ Lane Raffaldini Rubin