Above: pianist Jean-Yves Thibaudet

Author: Oberon

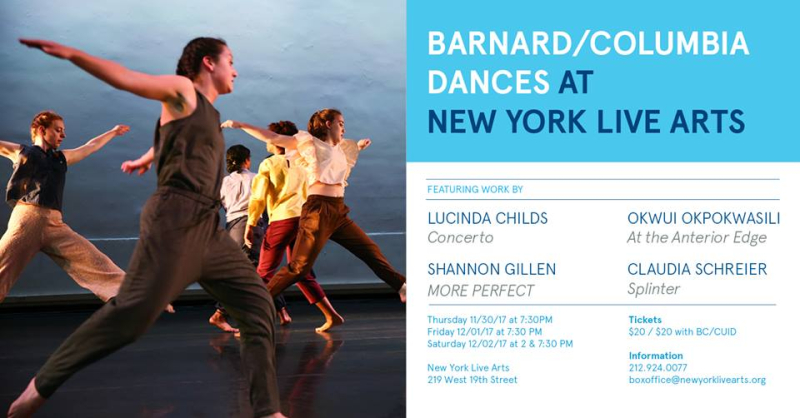

Saturday January 20th, 2018 matinee – This afternoon’s program at The New York Philharmonic might have been subtitled Music for Dancing: we heard a chamber score that’s been transformed into a ballet, and – after the interval – a succession of works inspired by dance forms: a sarabande, a set of waltzes, and finally a boléro that has become one of the most famous musical works ever created.

From time to time, The Philharmonic programs a chamber work; this not only adds a new dimension to a given performance, but affords fans of the orchestra an opportunity to enjoy hearing some of the esteemed artists of The Philharmonic in a front-and-center setting.

This afternoon, a sterling performance of César Franck’s Piano Quintet brought guest pianist Jean-Yves Thibaudet together with a quartet of extraordinary string players to play this gorgeous score – music used by choreographer Justin Peck for his lush and exquisite 2014 ballet Belles-Lettres at New York City Ballet.

César Franck had fallen in love with one of his pupils, Augusta Holmès, who he met in 1875. The Piano Quintet was written under the influence of Franck’s romantic obsession, and thus was detested by Madame Franck to the end of her days. Composer Camille Saint-Saëns (no less) played the piano for the Quintet’s premiere performance, but he seems to have been offended by the music’s sensuality; Saint-Saëns rejected Franck’s proposal of dedicating the quintet to him.

The players for the Franck quintet this afternoon were Sheryl Staples and Michelle Kim (violins), Cynthia Phelps (viola), and Eileen Moon-Myers (cello) with Mr. Thibaudet at the Steinway. The opening movement, Molto moderato quasi lento, commences with a violin theme played by Sheryl Staples; Ms. Staples throughout the Quintet played with ravishing lyricism. Mr. Thibaudet enters with a somewhat hesitant phrase, and then Ms. Moon-Myers’ dusky cello joins. The piano turns dreamy before a sudden eruption. Ms. Staples and Cynthia Phelps’ richly shaded viola savour every opportunity, and the Quintet has an especially nice role for the second violin which Ms. Kim set forth with lovely tone.

The strings play in unison over a turbulent piano motif; a change to a more pensive mood finds piano and strings alternating. There’s a spacious, impassioned passage before the movement’s enigmatic end.

Late seating at this point was a serious distraction; the players waited patiently as latecomers stumbled to their seats. Ms. Staples was then thankfully able to re-establish the mood quickly with her silken playing of the soft, longing theme over hushed keyboard that opens the Lento con molto sentimento. A heart-wrenching descending motif for piano and cello announces a hauntingly beautiful passage with a poignant mix of voices. Then Mr. Thibaudet takes up another set of descending notes, like raindrops – or heartbeats. Ms. Staples plays with overwhelming beauty; the hesitancy of the piano recurs, and the cellist sustains a remarkable deep note. Mr. Thibaudet in the high register and Ms. Staples’s sweetest tones bring this romantic reverie to an end.

The concluding Allegro non troppo ma con fuoco opens with Ms. Kim’s agitato figuration which Ms. Staples joins; the piano sounds almost ominous. Unison strings play over an active keyboard, evoking a sense of mystery and restlessness. A big, waltz-like buildup suddenly evaporates into an ethereal violin passage: Ms. Staples again at her finest. The music then grows unsettled in its rush to an abrupt finish.

Warm enthusiasm greeted the quintet of players as they came out for a bow; I had hopes of an encore, but the stage was now to be re-set for the full orchestra.

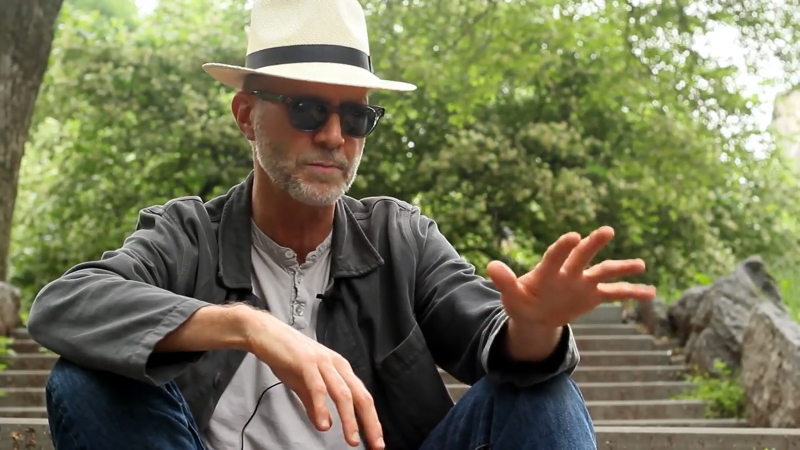

Joshua Weilerstein (above) took the podium for the second half of this afternoon’s program, which opened with Ravel’s orchestration of Claude Debussy’s Sarabande et Danse. The sarabande originated in Central America as a dance for women, accompanied by castanets; it had an Arabian lilt. But the sarabande was regarded as too provocative, and was banned. Later the French took it on as a much more staid dance, at a slower tempo.

Ravel’s setting of this piece, which Debussy wrote for solo piano, opens with a wind chorale; a full string section, with lovely basses, take over. Solo moments crop up – for clarinet (Anthony McGill), bassoon (Judith LeClair) and a trumpeter who I couldn’t see. The work ends with the sound of a gong which fades to nothingness. By contrast, the Danse was upbeat, showing Ravel’s orchestrational gifts to vivid effect. The harp and horn had their moments, and overall this coloristic, rhythmic little gem glowed.

The Valses nobles et sentimentales is a suite of waltzes published in 1911 by Maurice Ravel as piano solos; an orchestral version was published in 1912. The title was chosen in homage to Franz Schubert, who had published a set of waltzes in 1823 entitled Valses nobles and Valses sentimentales. The Ravel orchestrated setting has a strong balletic association: Balanchine used them for his eerie La Valse, wherein a young girl is stalked by Death in a haunted ballroom.

Mr. Weilerstein gave a vibrant interpretation, played fantastically by the huge orchestra. Mr. McGill (and a flautist I could not see from my location) made particularly fine impressions.

Ravel’s Boléro was the closing work on the program, and it’s always great fun to hear it played live. Ravel composed this best-known of his works in 1928 for a ballet choreographed by Bronislava Nijinsky for Ida Rubinstein. Consisting only of repetitions of the same C-major theme over the same insistent rhythm, Boléro hypnotizes with its constant shifts in instrumentation as the music unfolds in one long, slow crescendo.

The thrill of today’s performance for a devotee of the NY Phil such as myself was in hearing the various solo voices of the orchestra take up the tune: flute, clarinet, bassoon, saxophone (wow, this guy was really wailing!), and on and on in various combinations. And all the while, the relentlessly diligent strings pluck and the snare drums maintain the pace, starting softly and turning militant as the Boléro sways onward with mesmerizing inevitability.

The crowd went absolutely wild as Boléro ended: everyone stood up and yelled.

~ Oberon