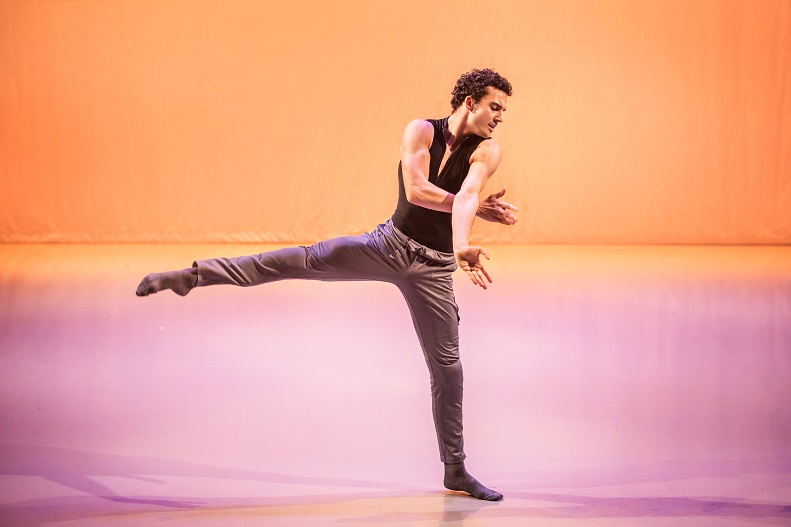

Above: The New York Philharmonic’s principal oboist Liang Wang

Sunday November 20th, 2016 – Music by French, Russian, German, and English composers was on offer this afternoon as a stellar ensemble of players from The New York Philharmonic took the stage at Merkin Hall. The group included some of the orchestra’s principals; the playing was divine, and all four works on the program were new to me.

The matinee opened with the String Trio of Jean Françaix, composed in 1933. Françaix was a child prodigy, writing his first music at age 6 and being published at age 10. His String Trio exemplifies the Neo-classical style which was enjoying favor at the time he wrote it; it consists of four movements, two of which are played with the strings muted. The excellent players – Shanshan Yao (violin), Peter Kenote (viola), and Qiang Tu (cello) – were clearly having a good time with this music, and their enjoyment was transmitted to the audience, who seemed quite taken with the piece.

The opening Allegretto vivo is a witty conversation among the three players; it has a gentle sway and a touch of jazz. With the musical lines in a state of perpetual motion, there is a sense of delicate charm in play. The following Scherzo – un-muted – is a sprightly dance played with a breezy ‘je ne sais quoi‘ quality. Plucking motifs and changes of pace eventually lead to a congenial if quirky waltz. The mutes are on for the Andante, which commences with wistful harmonies. Ms. Yao leads off with a sweet/sad song, taken up by Qiang Tu’s savorable cello and then by Mr. Kenote’s warm-toned viola: so lovely to hear each voice in succession. In a return to C-major, with the mutes set aside again, the lively start of the finale has an effervescent feeling (Mr. Kenote, in his opening remarks, spoke of a cancan). Things slow down a bit, with the violin playing over a plucked accompaniment. The pace then reaches sizzling speed, subsiding to lethargy before re-bounding to briskness and an actual march before vanishing on a surprisingly soft pizzicato. Such a fun piece!

Living in Paris in 1924, Sergei Prokofiev accepted a commission to compose a ballet for a touring troupe; the director asked for a short work for five instruments with a simple plot revolving around life with the circus. Prokofiev produced a quintet for the players the director had on hand: oboe, clarinet, violin, viola, and double bass. The ballet’s title was Trapeze. Since assembling this particular complement of instruments isn’t always easy, the work is not often performed; hearing it today made me wonder what the choreography would have been like.

Drawing from the Philharmonic roster, the instrumentation was handily (and expertly) filled out by a lively group of players, led by Anna Rabinova (violin), with Vivek Kamath (viola), Blake Hinson (bass – he also introduced the work) and wind virtuosos Sherry Sylar (oboe) and Pascual Martinez Forteza (clarinet).

The music definitely has a ‘circus’ atmosphere. A feeling of urban bustle with a slightly Mid-Eastern tinge pervades the opening movement, with oboe and clarinet vying phrase for phrase; the viola and then the violin join the fun, and the bass induces a lumbering motif. The music stalls, and turns pensive before bursting into a fast, flashy dance with violin screeching at us. The striding bass returns us to the opening oboe theme.

In the second movement, the bass growls at us and there’s an off-kilter feeling. The clarinet moves from burbling sounds to straightforward song; discord resolves into a major chord. The third movement, with a steady pacing, finds the clarinet and oboe trading sound-bytes; a swirling turbulence ensues.

In the fourth movement, an Adagio, the oboe sounds a bit ominous; the clarinet trills, the violin shivers, the bass creeps about. A violin melody melds into a dense tutti, with the oboe prominent. The plucking bass introduces the light-hearted fifth movement, with ironic gestures from the clarinet and oboe. The strings pluck and slash before Mr. Forteza’s clarinet polishes things off in fine style.

The final Andantino is whimsically dirge-like; there are clarinet cascades and the oboe gets insistent; the tread of the bass signals a minuet reprise. Suddenly alarms sound, and the piece rumbles raucously to a sudden end.

Several pages of Beethoven’s Quintet in E-flat major (originally penned in 1793) had gone missing by the time Leopold Zellner took up the task of ‘resuscitating’ it in 1862. Zellner relied strictly on the material evidence he found in Beethoven’s drafts in preparing a performing edition.

This work utilizes another off-beat assemblage of instruments: three horns, oboe, and bassoon. The horns – Richard Deane, R Allen Spanjer, and Howard Wall – enter in turn; their music veers from jaunty to Autumnal mellowness. As the work progressed, it became evident that the oboe was taking the most prominent position in terms of melodic opportunity: Liang Wang, the Philharmonic’s principal oboist, demonstrated both his striking virtuosity and his coloristic phrasing throughout the piece. Kim Laskowski’s bassoon seemed mostly limited to echo effects and to joining the horns; I kept hoping for a paragraph from her, but only a few phrases peeked thru the full-bodied sound of the horns.

A horn chorale initiates the Adagio maestoso, with the oboe again very much to the fore – and so attractively played by Mr. Wang. The concluding Minuetto begins brightly and brings us some really rich horn blends. Mr. Wang’s playing was exceptional, and it was a real pleasure to watch and hear him play his extended role here this afternoon, after so often enjoying his solo moments in the big repertory at Geffen Hall.

The Philharmonic’s principal horn, Philip Myers, introduced the concluding work – Ralph Vaughan Williams’ D-major Quintet – with a genuinely amusing speech in which he lamented the relative scarcity of chamber works featuring the horn and spoke of how he seized on the opportunity to play the Vaughan Williams today…which he did, to perfection.

Ralph Vaughan Williams’ Quintet in D-major had been withdrawn from circulation by the composer. He instructed his first wife not to publish it, but his second wife went ahead and did so, and thus we have this unusual work to enjoy today, more than a century after its premiere.

A deluxe quintet of Philharmonic artists gathered to perform the piece: alongside the resplendent sound of Mr. Myers’ horn, principal Anthony McGill’s clarinet playing was simply dazzling; violinist Lisa Kim (violin) and cellist Eileen Moon (my artistic crush) seized on the string passages to fine effect, whilst John Novacek underscored the ensemble beautifully from the keyboard, and relished his solo moments with some very cordial playing.

The four-movement quintet opens with an Allegro moderato initiated by clarinet and piano. A rolling theme for the ensemble sets up a round-robin of voices: piano, violin, clarinet, a horn summons, and cello speak up in turn. Things turn big and emphatic, and Phil Myers’ lush playing here was really grand, with Mr. Novacek ideally supportive. Cello, violin, and clarinet have another say before a shimmering motif from Mr. Novacek and a sustained phrase from Mr. Myers bring the movement to a close.

The second movement takes the form of an intermezzo; it has the feel of a Viennese waltz. Ms. Moon’s cello blends with the piano; later, Myers and McGill play in unison as the music sails on, with the piano taking up the waltz while Ms. Kim plays elegantly, incorporating a brief cadenza.

The velvety sound of the Myers horn sets up the Andantino, with Mr. Novacek’s evocative playing and another lovely passage from Ms. Kim leading into a melodic outpouring from all the voices. Fanfare-like motifs sound forth, and then a rich blending of timbres to savor. The horn plays over a rolling cello figure, and the music turns quite grand. Clarinet and violin descend, and the horn and piano glow gorgeously in a nostalgic theme.

The final Allegro molto induces toe-tapping from note one. Big horn-playing reigns, the clarinet and violin lead a merry dance, and a McGill cadenza with a perky trill delights us before the quintet reaches its boisterous end.

The Repertory:

FRANÇAIX – String Trio

PROKOFIEV – Quintet in G minor for Oboe, Clarinet, Violin, Viola, and Double Bass

BEETHOVEN – Quintet in E-flat major for Oboe, Three Horns, and Bassoon

VAUGHAN WILLIAMS – Quintet in D major for Clarinet, Horn, Violin, Cello, and Piano

The Participating Artists:

Richard Deane, horn

Pascual Martínez Forteza, clarinet

Blake Hinson, bass

Vivek Kamath, viola

Peter Kenote, viola

Lisa Kim, violin

Kim Laskowski, bassoon

Anthony McGill, clarinet

Eileen Moon, cello

Philip Myers, horn

John Novacek, piano

Anna Rabinova, violin

R. Allen Spanjer, horn

Sherry Sylar, oboe

Qiang Tu, cello

Howard Wall, horn

Liang Wang, oboe

Shanshan Yao, violin