A performance of Bellini’s NORMA from the Bolshoi in 1974 with Montserrat Caballé, Gianni Raimondi, Bruna Baglioni, and Ivo Vinco. Watch and listen here.

Category: Reviews

-

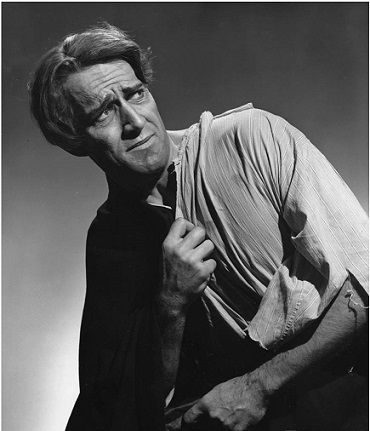

Gianni Raimondi

Above: Gianni Raimondi as Rodolfo in LA BOHEME

Tenor Gianni Raimondi was born at Bologna in 1923. He made his operatic debut in 1947 as the Duke in RIGOLETTO and was soon singing in opera houses throughout Italy. His career expanded to Nice, Marseille, Monte Carlo, Paris, London…

…and La Scala, where, in 1956, Mr. Raimondi made his debut in Luchino Visconti now-legendary production of LA TRAVIATA starring Maria Callas.

Callas and Raimondi (above) reunited the following year as Anna and Percy in Donizetti’s ANNA BOLENA. 1957 also marked the tenor’s debut at Vienna, where he was to appear regularly for twenty seasons.

In 1963, the Vienna State Opera’s production of LA BOHEME, under the direction of Herbert von Karajan, was filmed for posterity; Mirella Freni and Gianni Raimondi appeared as Mimi and Rodolfo. The performance is available on DVD.

Having debuted at San Francisco (1957) and the Teatro Colon (1959), Mr. Raimondi made his Metropolitan Opera debut as Rodolfo in BOHEME in 1965, opposite Ms. Freni.

Above: Freni and Raimondi in BOHEME

BOHEME was the only opera I saw Raimondi in at The Met. The performance was in September 1968, and his Mimi was Teresa Stratas; they were among the most moving of all the many interpreters of these roles I have seen thru the decades. My diary says the tenor was “…terrific…great upper range…beautiful portrayal…”

Mr. Raimondi remained at the Met until 1969; his other roles there were Pinkerton, Donizetti’s Edgardo, Faust, the Duke of Mantua, and Mario Cavaradossi. In 1968, the tenor joined Regine Crespin and Gabriel Bacquier in a thrilling broadcast performance of TOSCA, with Zubin Mehta conducting.

In the 1970s, Raimondi took on the spinto tenor roles in NORMA, I MASNADIERI, I VESPRI SIVILIANI, and SIMON BOCCANEGRA.

Following his retirement from the stage, the tenor lived in his villa by the sea at Riccione. He passed away in 2008.

Here is a collection of arias sung by Gianni Raimondi…some of these take a few seconds to start:

Gianni Raimondi – GIOCONDA aria

Gianni Raimondi – Recondita armonia ~ TOSCA

Gianni Raimondi ~ Nessun dorma – TURANDOT

~ Oberon

-

Premiere: Levine/Schenk GÖTTERDÄMMERUNG

During these endless days of being at home, I’ve been reading thru my opera diary, a hand-written document I started in 1962 and which now fills numerous file folders. So many wonderful memories of the great performances I saw over the years were stirred up by reading about them.One such exciting night was the 1988 premiere of the Otto Schenk GÖTTERDÄMMERUNG, the closing opera of Wagner’s epic RING Cycle. Often referred to affectionately as “the Levine RING”, full cycles of the production in the ensuing seasons created a great international buzz; Wagnerites from all over the globe gathered in New York City to witness this classic staging.

Having already seen the RHEINGOLD, WALKURE and SIEGFRIED, I had a pretty good idea of what to expect; still, when the Gibichung Hall loomed into view, it took my breath away. Levine was mostly magnificent, though there were moments when he let things drag a bit; his orchestra gave it their all, and the chorus sounded sensational as they gathered in lusty expectation of the double wedding.

As to the singers, here’s what I wrote upon returning to my room at the Colonial House after the performance:

“Casting was strong, with pretty singing from the Rhinemaidens – Joyce Guyer (in her Met debut), Diane Kesling, and Meredith Parsons – and Franz Mazura made an astoundingly vivid Alberich, singing with oily malice. The opening scene of Act II, with Alberich pawing at the sleeping Hagen, was very atmospheric.

The Gibichung brother and sister were rather curiously cast: as Gunther, Anthony Raffell’s voice sounded veiled and throaty, and Kathryn Harries’ beautiful (and beautifully acted) Gutrune was undone by effortful singing and a prominent vibrato. [I mentioned that Cornell MacNeil and Lucine Amara could have made for far more interesting casting in these roles!].

The Norn Scene, which I have always loved, benefited from the super casting of Mignon Dunn as 1st Norn, sung with richly doom-ladened tone. Hanna Schwarz (2nd Norn) had a couple of husky moments, but overall sang vividly, with excellent diction. As the 3rd Norn, Marita Napier sometimes sounded a bit insecure, but she did not let down the side. These three really made something of their opening discussion.

Toni Kramer sang erratically but acceptably in the torturous role of Siegfried. He seemed to be husbanding his powers, doing his best singing in Act III.

Above: Christa Ludwig as Waltraute and Hildegard Behrens as Brunnhilde

The divine Christa Ludwig made a thrilling Waltraute, singing with great clarity and verbal point. The distinctive Ludwig tone – that cherished sound – drew the audience in to her every phrase. Add to this the anguished urgency of her delivery, and the result was a veritable triumph.

The Ludwig Waltraute produced one of my all-time favorite curtain calls: stepping before the gold curtain for her first solo bow, she was greeted by such a din of applause and shouting that she halted in her tracks; her eyes opened wide in amazement, and she broke into a huge smile. It seemed to me that she had not expected such an avalanche of affection. She bowed deeply, clearly savoring this outpouring of love from the crowd.

The towering magnificence of Matti Salminen as Hagen (above) produced tremendous excitement in the House. His huge voice was at peak form, effortlessly filling the hall with sinister sound. In the scene where Hagen’s father appears to him in a dream, Salminen and Franz Mazura matched one another in both power and eerily expressive subtlety: thoroughly engrossing. The basso’s portrayal as the drama of Act II unfolded was towering in its epic nastiness and in his manipulation of the situation to attain the character’s sole goal: to regain the ring. This was a performance thrilling to behold, and to hear.

The roar of applause for each of Salminen’s solo bows was thunderous, and I was so excited to be part of it, shouting myself hoarse.

~ Sample the Salminen Hagen, from a later broadcast…it gives me he chills:

Matti Salminen as Hagen – Met 1993

Hildegard Behrens (above) was a Brunnhilde of terrifying intensity and incredible feminine strength. This was an overwhelming interpretation, in which voice and physicality combined to transcend operatic convention, reaching me on the deepest possible level. Behrens lived the part, in no uncertain terms.

The Dawn Duet found Behrens portraying the tamed warrior maid to perfection, savoring her domestic bliss but eager that Siegfried should go out into the world and do great deeds. Her unconventional beauty and her inhabiting of the character were so absorbing to behold. Later, In the scene with Waltraute, Behrens as Brunnhilde listened anxiously to all her sister’s words and she began to grasp the first signs of the downward spiral that would culminate with Siegfried’s betrayal and her own sacrifice. Even so, she dismissed Waltraute with fierce disdain. Behrens’ vivid depiction of Brunnhilde’s terror and helpless dejection as the false Siegfried wrested the ring from her was palpable.

In one of the evening’s most gripping moments, Behrens – having become possessed by Brunnhilde’s plight in Act II – responded to Siegfried’s oath by snatching Hagen’s spear away him and singing her own oath with blistering abandon. Totally immersed in the character, her pain was painful to behold. In the powerful trio that ends Act II, Behrens, Raffell, and Salminen were splendid.

Above: Hildegard Behrens as Brunnhilde ~ Immolation Scene

In the Immolation Scene, the great strength of Brunnhilde’s love for Siegfried, and her determination to perish in the flames of his funeral pyre, marked the culmination of Hildegard Behrens’ sensational performance. Her singing was powerful, with unstinting use of chest voice and flaming top notes; there were moments when expressionistic effects crept in but it all seemed so right. The amazing thing about Behrens’ singing and acting here was that it all seemed spontaneous…she seemed to be living it all in the moment. One cannot ask more of an operatic portrayal.

The curtain calls went on and on, the audience eager to show their appreciation with volleys of bravos as the singers stepped forward time and again. Here we must also thank James Levine, whose grand design underlies the great success to date of the individual operas. Ahead, in the Spring, seeing the full cycle in a week’s time is already on my calendar. My dream will come true!”

~ Oberon

-

John Aylward’s ANGELUS

Above: Paul Klee’s Angelus Novus (1920)

A New Focus Recordings release of John Aylward’s Angelus, performed by the Ecce Ensemble, has come my way. In the pre-dawn hours of yet another day of pandemic isolation, I put on my headphones and listened to the 40-minute work; I found it to be an engrossing sonic experience.

Above: composer John Aylward

Among the composer’s sources of inspiration for this work were the Paul Klee painting Angelus Novus, the stories of his mother’s experiences of fleeing Europe during World War II, and the words of great writer-philosophers from which the monodrama’s texts are drawn.

Adrienne Rich’s “What is Possible” is the first of the work’s ten movements, and also the longest. A setting of the poem by Adrienne Rich, it calls for both spoken and sung passages from the singer. Nina Guo has a wonderfully natural speaking voice, devoid of theatricality or affectation. The sung lines reveal Ms. Guo’s wide range, and her mastery of it. Coloristic writing for the instrumentalists will be a notable feature throughout the entire work; in this first section, the wind soloists dazzle. From this single track omward, the watchword of the enterprise seems to be clarity: it is perfectly recorded.

For the second track, the composer turns to Walter Benjamin’s “Angelus Novus”, a description of the Klee painting. The music is insectuous, the vocal line sometimes has a melting quality.

“Dream Images“, drawn from Nietzsche, opens with lecture-like spoken words, and an undercurrent of muzzled speech. Ms. Guo’s rhetoric can suddenly transform into flights of song. She speaks of the “…need for untruths…” and goes into a repetitious loop at “…our eyes glide only over the surface of things…”

Deft instrumentation sets forth in “The Abstract“, inspired by Schopenhauer’s The World as Will and Representation. The concrete (cello) contrasts with the abstract (oboe), mixing with Ms. Guo’s voice. The singer steps back for the closing lines (“…you are like an actor who has played your part…), spoken in a state of detachment.

Percussion and voice mesh in the miniature “Supreme Triumph” to a D.H. Lawrence text. This flows directly into “Secret Memory“, from Carl Jung’s Aion: Researches into the Phenomenology of the Self. The oboe is prominent and the voice flies high, with some uncanny sustained tones. The flute then joins the soprano in a kind of cadenza, ending with a wispy swoop.

This carries us into the seventh movement, Anima, a setting which blends words by the composer and Thomas Mann. As the flute warbles, the vocal line becomes quirky indeed – with clicks, hisses, and shushings. The text morph to German, with more vocal sound effects.

Plato’s Phaedrus, and phrases from the Catholic Angelus prayer, are sources for “Truth“. with its evocative instrumentation as the singer embarks on a sort of fantastical mad scene. Strings, winds, and percussion swirl along before subsiding to underpin the singer’s chanted prayer.

Plato holds his place for the ninth movement, the voice in lyrical flights interspersed with fragmented spoken lines. The music becomes intense, with ominous drums and screaming winds, as bells signal a warning before fading to stillness.

The final movement of Angelus is the most marvelous of all. A brooding prelude for the woodwinds emerges to a setting of excerpts from Weldon Kees’ A Distance from the Sea. The speech/song is pensive and illusive, with Ms. Guo in a reflective lyrical state. “Nothing will be the same…” she sings, in a moment now so strangely timely. “The night comes down…” she speaks, as the music turns soft and hazy, and then vanishes into air.

Above: Nina Guo

Nina Guo’s performance of Angelus is so impressive, and her colleagues from the Ecce Ensemble make the music truly vivid. The players are Emi Ferguson (flutes), Hassan Anderson (oboe), Barret Ham (clarinets), Pala Garcia (violin), John Popham (cello), and Sam Budish (percussion). Jean-Philippe Wurtz conducts.

The release date is April 24th, 2020. Look for it here, or (digitally) here.

~ Oberon

-

John Aylward’s ANGELUS

Above: Paul Klee’s Angelus Novus (1920)

A New Focus Recordings release of John Aylward’s Angelus, performed by the Ecce Ensemble, has come my way. In the pre-dawn hours of yet another day of pandemic isolation, I put on my headphones and listened to the 40-minute work; I found it to be an engrossing sonic experience.

Above: composer John Aylward

Among the composer’s sources of inspiration for this work were the Paul Klee painting Angelus Novus, the stories of his mother’s experiences of fleeing Europe during World War II, and the words of great writer-philosophers from which the monodrama’s texts are drawn.

Adrienne Rich’s “What is Possible” is the first of the work’s ten movements, and also the longest. A setting of the poem by Adrienne Rich, it calls for both spoken and sung passages from the singer. Nina Guo has a wonderfully natural speaking voice, devoid of theatricality or affectation. The sung lines reveal Ms. Guo’s wide range, and her mastery of it. Coloristic writing for the instrumentalists will be a notable feature throughout the entire work; in this first section, the wind soloists dazzle. From this single track omward, the watchword of the enterprise seems to be clarity: it is perfectly recorded.

For the second track, the composer turns to Walter Benjamin’s “Angelus Novus”, a description of the Klee painting. The music is insectuous, the vocal line sometimes has a melting quality.

“Dream Images“, drawn from Nietzsche, opens with lecture-like spoken words, and an undercurrent of muzzled speech. Ms. Guo’s rhetoric can suddenly transform into flights of song. She speaks of the “…need for untruths…” and goes into a repetitious loop at “…our eyes glide only over the surface of things…”

Deft instrumentation sets forth in “The Abstract“, inspired by Schopenhauer’s The World as Will and Representation. The concrete (cello) contrasts with the abstract (oboe), mixing with Ms. Guo’s voice. The singer steps back for the closing lines (“…you are like an actor who has played your part…), spoken in a state of detachment.

Percussion and voice mesh in the miniature “Supreme Triumph” to a D.H. Lawrence text. This flows directly into “Secret Memory“, from Carl Jung’s Aion: Researches into the Phenomenology of the Self. The oboe is prominent and the voice flies high, with some uncanny sustained tones. The flute then joins the soprano in a kind of cadenza, ending with a wispy swoop.

This carries us into the seventh movement, Anima, a setting which blends words by the composer and Thomas Mann. As the flute warbles, the vocal line becomes quirky indeed – with clicks, hisses, and shushings. The text morph to German, with more vocal sound effects.

Plato’s Phaedrus, and phrases from the Catholic Angelus prayer, are sources for “Truth“. with its evocative instrumentation as the singer embarks on a sort of fantastical mad scene. Strings, winds, and percussion swirl along before subsiding to underpin the singer’s chanted prayer.

Plato holds his place for the ninth movement, the voice in lyrical flights interspersed with fragmented spoken lines. The music becomes intense, with ominous drums and screaming winds, as bells signal a warning before fading to stillness.

The final movement of Angelus is the most marvelous of all. A brooding prelude for the woodwinds emerges to a setting of excerpts from Weldon Kees’ A Distance from the Sea. The speech/song is pensive and illusive, with Ms. Guo in a reflective lyrical state. “Nothing will be the same…” she sings, in a moment now so strangely timely. “The night comes down…” she speaks, as the music turns soft and hazy, and then vanishes into air.

Above: Nina Guo

Nina Guo’s performance of Angelus is so impressive, and her colleagues from the Ecce Ensemble make the music truly vivid. The players are Emi Ferguson (flutes), Hassan Anderson (oboe), Barret Ham (clarinets), Pala Garcia (violin), John Popham (cello), and Sam Budish (percussion). Jean-Philippe Wurtz conducts.

The release date is April 24th, 2020. Look for it here, or (digitally) here.

~ Oberon

-

Clifford Harvuot

Above, finalists in the Metropolitan Opera’s 1941-42 Auditions of the Air: tenor Elwood Gary, soprano Frances Greer, the Met’s General Manager Edward Johnson, soprano Margaret Harshaw, conductor Wilfred Pellertier, and baritone Clifford Harvuot.

As a winner of the Auditions of the Air, Clifford Harvuot’s first appearance on The Met stage came at a Sunday Night Gala on March 15, 1942. He sang the Prologo from PAGLIACCI. From then until December 21, 1975, the baritone chalked up nearly 1,300 performances with the Company, in New York City and on tour.

Harvuot particularly excelled in two Puccini roles, both of which brought out a feeling of ‘humanity’ in his voice. One was Sonora, the miner in FANCIULLA DEL WEST who is hopelessly in love with Minnie. It is Sonora who, in Act III, persuades the other miners that they must set Minnie’s beloved Dick Johnson free. Clifford Harvuot sing Sonora nearly 30 times at The Met, his Minnies being Leontyne Price, Dorothy Kirsten, and Renata Tebaldi.

He was also a very sympathetic Sharpless in MADAMA BUTTERFLY, appearing in the role with the great Butterflies of the day: Tebaldi, Albanese, Stella, Kirsten, and Tucci.

Helen Vanni – Carlo Bergonzi – Clifford Harvuot – BUTTERFLY trio – Met 1962

Other frequent Harvuot roles:

Angelotti in TOSCA

Schaunard in BOHEME

Alfio in CAVALLERIA RUSTICANA

Listen to Clifford Harvuot as Silvio in PAGLIACCI with Lucine Amara as Nedda here.

~ Oberon

-

Love Duet

On February 3rd, 1962, I tuned in to Texaco Metropolitan Opera Radio Network (as it was then called) and heard Puccini’s MADAMA BUTTERFLY sung live for the first time. Gabriella Tucci, who in my earliest years of opera mania was my favorite soprano, gave a magnificent performance. Carlo Bergonzi stepped in for the indisposed Sandor Konya, and this was a boon for me as Bergonzi was (and remains) my favorite tenor.

And so, the Tucci/Bergonzi rendering of the love duet from that matinee performance is very special to me:

Gabriella Tucci & Carlo Bergonzi – MADAMA BUTTERFLY ~ Love Duet – Met 1962

-

Moffo & Merrill ~ LA TRAVIATA @ The Met

~ Author: Oberon

By chance, I came upon this lovely Louis Melançon photo (above) of Anna Moffo and Robert Merrill in Verdi’s LA TRAVIATA in the Met’s 1966 Cecil Beaton production of the Verdi classic, which evoked in me memories of their partnership in this opera. From Moffo”s debut in 1959 til her final Met appearance in a staged opera there in 1976, they sang these roles together 50 times with the Company, in New York and on tour. They also made a beautiful recording of the opera together for RCA. Listen to a portion of their Act II duet here.

Moffo’s 1959 Met debut came at The Old Met in the Tyrone Guthrie production. On September 24th, 1966, during the second week at the New Met, Cecil Beaton’s lavish production opened with Moffo, Merrill, and tenor Bruno Prevedi in the leading roles. Georges Prêtre was on the podium. I saw the Moffo Violetta four times, twice with Merrill as Germont, and twice with Mario Sereni, who was very good in the role, and a less ‘wooden’ actor than Merrill.

Above: Moffo as Violetta in the scene at Flora’s party

Anna Moffo had two Saturday matinee broadcasts of TRAVIATA in the Beaton production, nine months apart. For me, they offered tell-tale signs of what would be the diva’s eventual vocal decline. In the first broadcast, on March 25th, 1967, she sounded fantastic: the voice lyrical and free-flowing, the top gorgeous, the drama expressed thru colour rather than force: in sum, one of her great performances.

During June, 1967, I saw two more Moffo Violettas (one with Merrill, the second with Sereni) and she was very impressive indeed, receiving huge ovations. I met her at the stage door; she was extremely beautiful in person, and very kind.

On December 30, 1967, Moffo had her second matinee broadcast in the Beaton production. I was very excited to be seeing her onstage again, but from her very first line – “Flora, amici, la notte che resta...” – something had changed. On “…che resta..” she really leaned heavily on the low notes, sounding almost chesty. I was still a novice opera-lover at that time, but alarm bells went off. Moffo continued to pressurize her lower notes throughout the first act, but the coloratura and high notes of “Sempre libera” seemed fine.

During the intermission, I asked a fellow Moffo fan if her vocalism that day was worrisome to him; he felt she was making an effort to sound more ‘dramatic’, and he didn’t feel panicky about it. The soprano continued singing in this manner for the rest of the opera, and – since the drama gets increasingly intense as the story unfolds – we heard these big, juicy lower notes from Moffo throughout the afternoon.

As it turned out, I never saw Anna Moffo on The Met stage again after that, though she continued singing there for nearly a decade. On February 1, 1969, came the disastrous LUCIA DI LAMMERMOOR broadcast, which I listened to in disbelief, which gave way to despair. The voice was wildly unpredictable: woozy in the middle, over-ripe in the lower range, and screamy at the top. Awkwardly, I ran into her in the Met lobby a couple of weeks afterward and she recognized me; she asked if I had heard the LUCIA broadcast, and I gave a neutral response. She said she had been ill that day, but that now things were back to normal.

I cannot say for certain whether she ever regained peak form again, but from reports from friends, she was not singing with the lustre and ease we’d come to expect from her. Her later recordings are so sad…I cannot listen to them.

In 1975, TJ and I – living in Hartford – tuned in for her broadcast of Nedda in PAGLIACCI. Moffo sounded dreadful, the voice unsupported. “What is she thinking?” I asked TJ. “I guess she feels she still has something to offer,” he replied.

In 1979, I was still living in Hartford (but no longer with TJ) when Moffo came to The Bushnell to sing MERRY WIDOW in English. I decided to go, and always regretted it afterwards.

Anna Moffo and Robert Merrill reunited on the Met stage one last time for the Met’s 100th Anniversary Gala on October 22, 1983. They sang the duet “Sweethearts“ from Sigmund Romberg’s MAYTIME. The audience greeted them affectionately, and they managed to get thru their duet without mishap.

I hadn’t intended to delve into the story of Moffo’s decline when I posted the photo at the top of the article; I prefer simply to remember her lovely performances from the first decade of her Met career. But one thing led to another once I started writing.

One of the most moving passages in her performances as Violetta was her farewell to Alfredo in Act II, when she thinks she will never see him again. In the Beaton production, this was staged so that Violetta came downstage while sustaining the top B-flat and sank to her knees, clasping Alfredo’s hand. Here is the phrase – “Amami, Alfredo…!” as Ms. Moffo sang it at La Scala in 1964:

Anna Moffo – Amami Alfredo! ~ TRAVIATA (Live)

And here is Moffo at her best, from a commercial arias compilation, conducted by Sir Colin Davis:

Anna Moffo – TRAVIATA ~ Act I scena (commercial recording)

~ Oberon

-

Moffo & Merrill ~ LA TRAVIATA @ The Met

~ Author: Oberon

By chance, I came upon this lovely Louis Melançon photo (above) of Anna Moffo and Robert Merrill in Verdi’s LA TRAVIATA in the Met’s 1966 Cecil Beaton production of the Verdi classic, which evoked in me memories of their partnership in this opera. From Moffo”s debut in 1959 til her final Met appearance in a staged opera there in 1976, they sang these roles together 50 times with the Company, in New York and on tour. They also made a beautiful recording of the opera together for RCA. Listen to a portion of their Act II duet here.

Moffo’s 1959 Met debut came at The Old Met in the Tyrone Guthrie production. On September 24th, 1966, during the second week at the New Met, Cecil Beaton’s lavish production opened with Moffo, Merrill, and tenor Bruno Prevedi in the leading roles. Georges Prêtre was on the podium. I saw the Moffo Violetta four times, twice with Merrill as Germont, and twice with Mario Sereni, who was very good in the role, and a less ‘wooden’ actor than Merrill.

Above: Moffo as Violetta in the scene at Flora’s party

Anna Moffo had two Saturday matinee broadcasts of TRAVIATA in the Beaton production, nine months apart. For me, they offered tell-tale signs of what would be the diva’s eventual vocal decline. In the first broadcast, on March 25th, 1967, she sounded fantastic: the voice lyrical and free-flowing, the top gorgeous, the drama expressed thru colour rather than force: in sum, one of her great performances.

During June, 1967, I saw two more Moffo Violettas (one with Merrill, the second with Sereni) and she was very impressive indeed, receiving huge ovations. I met her at the stage door; she was extremely beautiful in person, and very kind.

On December 30, 1967, Moffo had her second matinee broadcast in the Beaton production. I was very excited to be seeing her onstage again, but from her very first line – “Flora, amici, la notte che resta...” – something had changed. On “…che resta..” she really leaned heavily on the low notes, sounding almost chesty. I was still a novice opera-lover at that time, but alarm bells went off. Moffo continued to pressurize her lower notes throughout the first act, but the coloratura and high notes of “Sempre libera” seemed fine.

During the intermission, I asked a fellow Moffo fan if her vocalism that day was worrisome to him; he felt she was making an effort to sound more ‘dramatic’, and he didn’t feel panicky about it. The soprano continued singing in this manner for the rest of the opera, and – since the drama gets increasingly intense as the story unfolds – we heard these big, juicy lower notes from Moffo throughout the afternoon.

As it turned out, I never saw Anna Moffo on The Met stage again after that, though she continued singing there for nearly a decade. On February 1, 1969, came the disastrous LUCIA DI LAMMERMOOR broadcast, which I listened to in disbelief, which gave way to despair. The voice was wildly unpredictable: woozy in the middle, over-ripe in the lower range, and screamy at the top. Awkwardly, I ran into her in the Met lobby a couple of weeks afterward and she recognized me; she asked if I had heard the LUCIA broadcast, and I gave a neutral response. She said she had been ill that day, but that now things were back to normal.

I cannot say for certain whether she ever regained peak form again, but from reports from friends, she was not singing with the lustre and ease we’d come to expect from her. Her later recordings are so sad…I cannot listen to them.

In 1975, TJ and I – living in Hartford – tuned in for her broadcast of Nedda in PAGLIACCI. Moffo sounded dreadful, the voice unsupported. “What is she thinking?” I asked TJ. “I guess she feels she still has something to offer,” he replied.

In 1979, I was still living in Hartford (but no longer with TJ) when Moffo came to The Bushnell to sing MERRY WIDOW in English. I decided to go, and always regretted it afterwards.

Anna Moffo and Robert Merrill reunited on the Met stage one last time for the Met’s 100th Anniversary Gala on October 22, 1983. They sang the duet “Sweethearts“ from Sigmund Romberg’s MAYTIME. The audience greeted them affectionately, and they managed to get thru their duet without mishap.

I hadn’t intended to delve into the story of Moffo’s decline when I posted the photo at the top of the article; I prefer simply to remember her lovely performances from the first decade of her Met career. But one thing led to another once I started writing.

One of the most moving passages in her performances as Violetta was her farewell to Alfredo in Act II, when she thinks she will never see him again. In the Beaton production, this was staged so that Violetta came downstage while sustaining the top B-flat and sank to her knees, clasping Alfredo’s hand. Here is the phrase – “Amami, Alfredo…!” as Ms. Moffo sang it at La Scala in 1964:

Anna Moffo – Amami Alfredo! ~ TRAVIATA (Live)

And here is Moffo at her best, from a commercial arias compilation, conducted by Sir Colin Davis:

Anna Moffo – TRAVIATA ~ Act I scena (commercial recording)

~ Oberon