Kerstin Meyer sings Konchakovna’s cavatina from Borodin’s PRINCE IGOR. Meyer sang the role of the Composer in the Metropolitan Opera premiere of Strauss’s ARIADNE AUF NAXOS in 1962, having previously appeared there as Carmen and Gluck’s Orfeo.

Category: Reviews

-

At ABT: Paloma Herrera’s Farewell

Wednesday May 27th, 2015 matinee – Farewells are always bittersweet, and this afternoon at ABT as Paloma Herrera took her final bows with the Company, it seemed rather sad that she should be leaving us since she is in gorgeous physical shape, technically polished to perfection, exuding prima ballerina confidence, and wildly popular with audiences.

Sometimes at a farewell, the occasion overshadows the actual work being performed, but this afternoon’s GISELLE was excellent in every way. Paloma’s Giselle is a classic: the marvelous feet, the expressive hands; the clarity with which she presents the character’s hopefulness, her illness, her devotion to Loys, the devastation of his betrayal, and her fall into madness and death all so perfectly projected in Act I. As a Wili, she is able to portray both spectral remoteness and human tenderness in perfect measure.

Her Act I solo – the hops on pointe and then a swift, swirling manège – drew screams of delight from the audience, and her Wili solo in Act II literally stopped the show: she was called out twice to ecstatic applause. For all the brilliant surety of her dancing, it was her simple gesture of steadfast love after having saved Albrecht that will always linger in the memory.

Roberto Bolle is a blindingly handsome Albrecht, and handsome is as handsome does: his dancing and partnering are superb. As he watches Giselle being crowned queen of the harvest, Bolle’s eyes reveal his foresight: “My number’s up, this will all end soon.” We cannot quite tell if he’s taken his village romance seriously or has viewed it as a lark: whichever is the case, he is almost cripplingly devastated by remorse in Act II.

Bolle’s bravura solo in Act II and his long series of entrechats were much admired by the audience; he and Paloma sustained a spiritual link throughout their other-worldly encounter, imbuing the adagio with the palpable sense of a dream from which he hopes never to awaken.

The most moving moment of the performance came with their final parting. As Herrera/Giselle was about to descend into her tomb, she stretched out her hand to the bereft Bolle/Albrecht to give him a single flower. He can barely reach her, barely grasp the blossom…her token of forgiveness. That’s when I burst into tears.

The cast was a strong one down the line, with Thomas Forster’s towering Hilarion, Susan Jones’s clearly mimed presage of disaster as Berthe, and Luciana Paris’s luscious Bathilde all making a fine effect. Youthful brio and charm marked the Peasant pas de deux as danced by Skylar Brandt and Aaron Scott, with Skylar bringing a touch of rubato to her first solo. In Act II, Devon Teuscher’s Myrthe was imperious and sublimely danced, and Melanie Hamrick and Leann Underwood as the principal Wilis floated thru their solo passages with Sylph-like grace.

The final ovation was monumental: many of Ms. Herrera’s partners – past and present – and seemingly the entire current ABT roster filled the stage to honor her, heaping flowers at the ballerina’s feet. The applause went on and on, with a group of devoted fans yelling “PA-LO-MA! PA-LO-MA!!” At last she appeared alone before the Met’s gold curtain to a veritable avalanche of applause and cheers.

-

Gerstein/Mälkki @ The NY Philharmonic

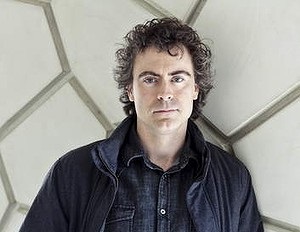

Above: pianist Kirill Gerstein, photographed by Marco Borggreve

Saturday May 21st, 2015 – Pianist Kirill Gerstein returned to The New York Philharmonic for a series of concerts featuring his playing of the Brahms Piano Concerto No. 1. Conducted by Susanna Mälkki, the other programmed works were Brahms’s Variations on a Theme by Haydn and Jonathan Harvey’s Tranquil Abiding.

The title Variations on a Theme by Haydn has stuck, even after modern scholarship has established that the theme was actually not by Haydn; instead it may have been drawn from an old pilgrim hymn known as “Chorale Sti. Antonii.”

Brahms’s eight variations are well-contrasted in tempo and character; the music is perfectly pleasing and was of course beautifully played by The Philharmonic tonight. There is, however, little of emotional value here; Ms. Mälkki’s rather formal, almost military style of conducting suited the music well.

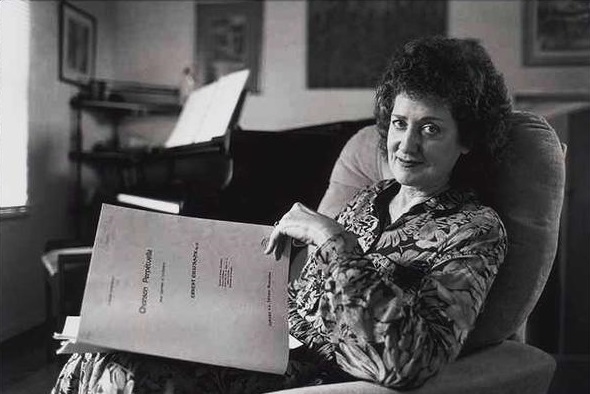

Above: conductor Susanna Mälkki

The conductor seemed far more distinctive in Tranquil Abiding, composed by Jonathan Harvey in 1998. In this imaginative, transcendent work which begins almost imperceptibly, the composer evokes the act of breathing with a continuous inhale/exhale motif developed thru sustained crescendos and decrescendos. The deep reverberations of the gong have a spiritual resonance, whilst fragmented warblings from the wind players refer to the natural world. After a turbulent passage, with the winds jabbering, the music settles back into calm; the high violins soar in ethereal radiance before fading to nothingness. This mystical work held the audience enthralled, and the conductor and players seemed deeply invested in its austere beauty.

After the interval, Kirill Gerstein, Ms. Mälkki, and the Philharmonic gave a grand performance of the Brahms Piano Concerto #1. Right from the start, the conductor’s vividly dramatic view of the work evinced itself in glorious swirls of sound. The pianist, passionate and musically authoritative, wove the keyboard themes gleamingly into the orchestral tapestry; in the last of the first movement’s cadenzas, Mr. Gerstein’s playing had a particularly resonant appeal. The calm of the Adagio found the pianist at his most poetic; the movement ends with a feeling of deep serenity. But then immediately we are plunged into the boisterous finale with its gypsy colourings, the pianist tossing off brilliant passages with flair. The Philharmonic horns were having a fine night and added much to the enjoyment of the concerto.

-

Berlioz’s THE TROJANS @ Covent Garden 1957

A recording of the Royal Opera’s 1957 English-language production of Hector Berlioz’s monumental opera THE TROJANS has come my way and it has many felicitous elements. The translation appropriately relies on Early Modern English pronouns (thee/thou/thine) to evoke the ancient kingdoms of Troy and Carthage. With a few passing cuts in this epic opus, Rafael Kubelik helms the performance impressively and the sound quality is quite good for a recording made 50+ years ago.

For years after I discovered opera in 1959, I subscribed to the British magazine OPERA. The cast of this TROJANS is full of ‘Covent Garden’ names that were familiar to me thru the magazine long before I heard any of their actual voices: people like Amy Shuard, Forbes Robinson, Noreen Berry, Marie Collier, Joan Carlyle, Michael Langdon, and Lauris Elms.

At The Met, Blanche Thebom was an established star (Met debut 1944) by the time she appeared as Dido in London, and Jon Vickers made his role-debut as Aeneas in this ’57 performance, which became a signature part for the great tenor.

Curiously, this is a performance in which each of the three principal singers proves less than ideal, yet the overall performance – thanks to Maestro Kubelik and the strong supporting cast – still makes a vivid impression.

Amy Shuard does not seem absolutely at home in the role of Cassandra; she has passing pitch problems and some of the music seems to lay too low for her to make her finest impression. Her commitment is undoubted, and her sense of the drama and her fine high notes are positive aspects. But often one just wants more power and colour in the lower-middle and lowest ranges of this music, which rather awkwardly straddles the mezzo/soprano divide.

Blanche Thebom as Dido has the right aristocratic feeling for Dido’s music; she becomes more passionate as her love for Aeneas is inflamed – and then thwarted – by destiny. Thebom’s strong top notes stand out, and she fills scene after scene with perfectly good singing; yet her voice sometimes seems matronly and a bit lacking in tonal bloom.

It would be nice to be able to say that Jon Vickers’ first Aeneas was an unalloyed triumph, but despite his excellent diction and superbly individual voice – which amply conveys the the character’s innate humanity and rather grizzled tenderness – and his sense of vocal identification with every aspect of the hero’s personality, he is not at ease in the role’s top-most notes. He omits the highest vocal arc of the love duet, reveals some effort in the demanding “Inutiles Regrets!” and seems rather uncomfortable in his final cry of “Italie!” As Vickers sang the role in the ensuing years, his voice found itself increasingly at home in this demanding music; and indeed even here in 1957 there is much impressive singing.

Despite some reservations about both Thebom and Vickers, they do achieve some especially fine soft harmonies as they sing of the mysterious wonders of love in the great duet “Nuit d’ivresse.”

The stalwart baritone Jess Walters sings strongly as Chorebus; his duet with Ms. Shuard is full of apt dramatic touches from both singers – and the soprano’s concluding top-B is her best note of the performance.

Lauris Elms (above) makes an especially lovely impression as Dido’s sister, Anna. Anna’s role includes two wonderful duets: the first, with Dido, in which she urges her widowed sister to consider opening her heart to another love; and the second, with Dido’s minister Narbal. Narbal’s concerns about the effects of the Dido/Aeneas attachment on Dido’s ability to rule are brushed off by her sister who is so delighted at Dido’s new-found happiness. Ms. Elms has a full-throated lyric mezzo sound and dips into her lower range without over-emphasis; her voice is clear and so is her diction. I keep going back to Anna’s two duets, just to enjoy Ms. Elms’ vocalism.

Joining Lauris Elms in the Anna/Narbal duet, basso David Kelly – who was an indispensable Covent Garden regular for fifteen years – is a perfect match for the mezzo; his diction and well-produced voice make for a very effective portrayal.

I was particularly pleased with the Iopas of Richard Verreau (above); this French-Canadian tenor was my first Faust in a performance at the Old Met in 1963. He sings the high-lying solo “O blonde Cérès” quite beautifully, in a more passionate and extroverted interpretation of the aria than is sometimes heard. In the second of LES TROYENS’ two taxing and exposed solos for lyric tenors, Irishman Dermot Troy sings the plaintive aria of the homesick sailor Hylas with attractive lyricism.

TROYENS is such a unique and treasure-filled opera; whatever concerns this recording raises, I am sure I will return to it time and again.

-

Berlioz’s THE TROJANS @ Covent Garden 1957

A recording of the Royal Opera’s 1957 English-language production of Hector Berlioz’s monumental opera THE TROJANS has come my way and it has many felicitous elements. The translation appropriately relies on Early Modern English pronouns (thee/thou/thine) to evoke the ancient kingdoms of Troy and Carthage. With a few passing cuts in this epic opus, Rafael Kubelik helms the performance impressively and the sound quality is quite good for a recording made 50+ years ago.

For years after I discovered opera in 1959, I subscribed to the British magazine OPERA. The cast of this TROJANS is full of ‘Covent Garden’ names that were familiar to me thru the magazine long before I heard any of their actual voices: people like Amy Shuard, Forbes Robinson, Noreen Berry, Marie Collier, Joan Carlyle, Michael Langdon, and Lauris Elms.

At The Met, Blanche Thebom was an established star (Met debut 1944) by the time she appeared as Dido in London, and Jon Vickers made his role-debut as Aeneas in this ’57 performance, which became a signature part for the great tenor.

Curiously, this is a performance in which each of the three principal singers proves less than ideal, yet the overall performance – thanks to Maestro Kubelik and the strong supporting cast – still makes a vivid impression.

Amy Shuard does not seem absolutely at home in the role of Cassandra; she has passing pitch problems and some of the music seems to lay too low for her to make her finest impression. Her commitment is undoubted, and her sense of the drama and her fine high notes are positive aspects. But often one just wants more power and colour in the lower-middle and lowest ranges of this music, which rather awkwardly straddles the mezzo/soprano divide.

Blanche Thebom as Dido has the right aristocratic feeling for Dido’s music; she becomes more passionate as her love for Aeneas is inflamed – and then thwarted – by destiny. Thebom’s strong top notes stand out, and she fills scene after scene with perfectly good singing; yet her voice sometimes seems matronly and a bit lacking in tonal bloom.

It would be nice to be able to say that Jon Vickers’ first Aeneas was an unalloyed triumph, but despite his excellent diction and superbly individual voice – which amply conveys the the character’s innate humanity and rather grizzled tenderness – and his sense of vocal identification with every aspect of the hero’s personality, he is not at ease in the role’s top-most notes. He omits the highest vocal arc of the love duet, reveals some effort in the demanding “Inutiles Regrets!” and seems rather uncomfortable in his final cry of “Italie!” As Vickers sang the role in the ensuing years, his voice found itself increasingly at home in this demanding music; and indeed even here in 1957 there is much impressive singing.

Despite some reservations about both Thebom and Vickers, they do achieve some especially fine soft harmonies as they sing of the mysterious wonders of love in the great duet “Nuit d’ivresse.”

The stalwart baritone Jess Walters sings strongly as Chorebus; his duet with Ms. Shuard is full of apt dramatic touches from both singers – and the soprano’s concluding top-B is her best note of the performance.

Lauris Elms (above) makes an especially lovely impression as Dido’s sister, Anna. Anna’s role includes two wonderful duets: the first, with Dido, in which she urges her widowed sister to consider opening her heart to another love; and the second, with Dido’s minister Narbal. Narbal’s concerns about the effects of the Dido/Aeneas attachment on Dido’s ability to rule are brushed off by her sister who is so delighted at Dido’s new-found happiness. Ms. Elms has a full-throated lyric mezzo sound and dips into her lower range without over-emphasis; her voice is clear and so is her diction. I keep going back to Anna’s two duets, just to enjoy Ms. Elms’ vocalism.

Joining Lauris Elms in the Anna/Narbal duet, basso David Kelly – who was an indispensable Covent Garden regular for fifteen years – is a perfect match for the mezzo; his diction and well-produced voice make for a very effective portrayal.

I was particularly pleased with the Iopas of Richard Verreau (above); this French-Canadian tenor was my first Faust in a performance at the Old Met in 1963. He sings the high-lying solo “O blonde Cérès” quite beautifully, in a more passionate and extroverted interpretation of the aria than is sometimes heard. In the second of LES TROYENS’ two taxing and exposed solos for lyric tenors, Irishman Dermot Troy sings the plaintive aria of the homesick sailor Hylas with attractive lyricism.

TROYENS is such a unique and treasure-filled opera; whatever concerns this recording raises, I am sure I will return to it time and again.

-

Season Finale: Score Desk for BALLO IN MASCHERA

Above: Dmitry Hvorostovsky and Sondra Radvanovsky

Tuesday April 28th, 2015 – For my final Met performance of the current season, Verdi’s BALLO IN MASCHERA with probably the strongest overall cast of any opera produced at the Met this season. I felt no need to see the Met’s mixed-bag, neither-here-nor-there production again, so I was back at my score desk. Of the twenty-plus performances I attended at the Met this season, most were experienced from score desks; there is less and less of a need to actually see what it happening onstage, so why spend the money on a ‘room with a view’? And besides, I hardly ever stay to the end of anything thanks to the slow agony of the Gelb-length intermissions. Tonight, though, my two amusing friends Adi and Craig helped make the long breaks somewhat more tolerable.

Tonight’s audience was one of the largest I’ve seen at the opera all season. The Met’s always been a ‘singers house’; the box office is voice-driven and has been since the days of de Reszke and Caruso. There was Flagstad, and Birgit and Franco; and there was Pav, and now there’s Netrebko and Kaufmann. People come for the singing because that’s what opera is all about.

The evening began with an announcement that James Levine would be replaced on the podium by John Keenan. This may have been a rather last-minute decision since Levine’s special wheelchair platform was in place. Keenan is a very fine Wagner conductor, but in the Italian repertoire Joseph Colaneri would be my choice if Levine is ailing. Much of Act I tonight had an unkempt quality; the singers seemed to want different tempi than Keenan was offering them, and they tended to speed ahead, leaving the orchestra to catch up.

Piotr Beczala – superb in IOLANTA earlier in the season – sounded a bit tired in Act I. His opening aria was not smooth and the climactic top A-sharp was tight and veered above pitch. He began to settle in vocally at Ulrica’s, though the (written) low notes in “Di tu se fedele” were clumsily handled – no one would have cared if he’d sung them up an octave. By the time he reached the great love duet, Beczala was sounding much more like his usual self, and his “Non sai tu che se l’anima mia” was particularly fine. Spurred on by his resplendent soprano, the Polish tenor invested the rest of the duet with vibrant, passionate singing.

As Ulrica, Dolora Zajick was exciting: the voice has its familiar amplitude and earthy chest notes intact and she also sang some beautiful piani, observing Verdi’s markings. It’s not her fault that the production idiotically calls for amplification of her deep call for “Silenzio!” at the end of her aria. Dolora’s chest tones don’t need artificial enhancement.

Heidi Stober was a serviceable Oscar; her highest notes could take on a brassy edge and overall she lacked vocal charm. Memories of Reri Grist, Roberta Peters, Judith Blegen, Lyubov Petrova, and Kathleen Kim kept getting in my ear, perhaps unfairly.

Dmitry Hvorostovsky as Count Anckarström was in splendid voice from note one, and his opening aria “Alla vita che t’arride” was beautifully phrased with a suave legato, the cadenza rising up to a majestically sustained high note. In the scene at the gallows (or rather – as this production places it – “in an abandoned warehouse…”) the baritone was vividly involved, first as a loyal friend urging his king to flee and later as the shamed, betrayed husband.

Sondra Radvanovsky, who in 2013 gave us a truly impressive Norma at The Met, was – like the baritone – on top form. With a voice utterly distinctive and unlike any other, and with the seemingly innate ability to find the emotional core of any role she takes on, Radvanovsky has a quality of vocal glamour that makes her undoubtedly the most exciting soprano before the public today. What makes her all the more captivating is that, if a random note has a passing huskiness or isn’t quite sounding as she wants it to, she’s able to make pinpoint adjustments and forge ahead. This makes her singing interesting and keeps us on high alert, wondering what she’ll do next. Thus she generates a kind of anticipatory excitement that is rare these days.

Launching Amelia’s “Consentimi o signore’ in the Act I trio, Sondra shows off the Verdian line of which she alone today seems true mistress. When we next meet her, she is out on her terrified search for the magical herb. Unfurling the grand recitative “Ecco l’orrido campo…” with instinctive dramatic accents, she draws us into Amelia’s plight. The great aria that follows is a marvel of expressiveness (though I do wish she would eliminate the little simpering whimpers during the orchestral bridge…a pointless touch of verismo); and then terror seizes her and she goes momentarily mad before calming herself with the great prayerful ascent to the high-C. The ensuing cadenza was both highly emotional and superbly voiced.

In the love duet, with Beczala now vocally aflame, Sondra gave some of her most incredibly nuanced, sustained singing at “Ma tu, nobile…”- astounding control – before the two singers sailed on to the impetuous release of the duet’s celebratory finale and ended on a joint high-C.

Amelia’s husband unexpectedly appears to warn the king that his enemies are lurking; after Gustavo has fled (has Sondra ever contemplated taking a high-D at the end of the trio here? I’ve heard it done…), soprano and baritone kept the excitement level at fever pitch during the scene with the conspirators: page after page of Verdian drama marvelously voiced, ending with a rich high B-flat from the soprano as she is hauled off to be punished.

I hate the break in continuity here: ideally we would follow the couple home and the intensity level would suffer no letdown; instead we have another over-long intermission.

But the mood was quickly re-established when the curtain next rose: Hvorostovsky thundering and growling while Radvanovsky pleads for mercy. Now the evening reached a peak of vocal splendour as the soprano sang her wrenchingly poignant plea “Morro, ma prima in grazia…” Displaying a fascinating command of vocal colour and of dynamics that ranged from ravishing piani to gleaming forte, the soprano was in her greatest glory here, with a spectacular cadenza launched from a sublime piano C-flat before plunging into the heartfelt depths and resolving in a ravishingly sustained note of despair.

Hvorostovsky then seized the stage. In one of Verdi’s most thrilling soliloquies, the character moves from fury to heartbreak. After the snarling anger of “Eri tu”, Dima came to the heart of the matter: using his peerless legato and vast palette of dynamic shadings, he made “O dolcezze perdute, o memorie…” so affecting in its tragic lyricism before moving to a state of resignation and finishing on a gorgeously sustained final note. In the scene of the drawing of lots, Hvorostovsky capped his triumph with an exultant “Il mio nome! O giustizia del fato!” – “My name! O the justice of fate: revenge shall be mine!” His revenge will bring only remorse.

We left after this scene, taking with us the fresh memory of these two great singers – Radvanovsky and Hvorostovsky – having shown us why opera remains a vital force in our lives.

Metropolitan Opera House

April 28, 2015UN BALLO IN MASCHERA

Giuseppe VerdiAmelia.............................Sondra Radvanovsky

Riccardo (Gustavo III).............Piotr Beczala

Renato (Count Anckarström).........Dmitri Hvorostovsky

Ulrica (Madame Ulrica Arvidsson)...Dolora Zajick

Oscar..............................Heidi Stober

Samuel (Count Ribbing).............Keith Miller

Tom (Count Horn)...................David Crawford

Silvano (Cristiano)................Trevor Scheunemann

Judge..............................Mark Schowalter

Servant............................Scott ScullyConductor..........................John Keenan

-

Great Performers: Lisa Batiashvili/Paul Lewis

Monday March 30th, 2015 – Violinist Lisa Batiashvili (above) joined pianist Paul Lewis for this recital at Alice Tully Hall, the second event of our Great Performers at Lincoln Center subscription series. Sonatas by Schubert and Beethoven book-ended the programme, with some delicious treats in between.

Ms. Batiashvili, who is artist-in-residence for the current New York Philharmonic season, is a slender, elegant beauty gowned in rose-pink. From the opening measures of the Schubert ‘Duo’ in A-major, she and Mr. Lewis formed an ideal alliance: both players are masters of subtlety, the violinist with her shining clarity of tone, the pianist capable of great delicacy as well as a sense of gentle urgency. Throughout the sonata’s opening Allegro moderato, their mutual musicality yielded an uncommonly lovely experience, drawing the large audience into Schubert’s world.

In the exuberant charm of the Scherzo which follows, the two players mixed virtuosity with fleeting passages of ‘sung’ melody; then came the Andantino, with its poignant theme and gracious motif of trills where the artists lingered in music’s expressive delights. The final Allegro vivace blends declamation and lilt, carrying us along with its waltzing buoyancy.

As a sort of mega-encore, Ms. Batiashvili and Mr. Lewis offered a vibrant performance of Schubert’s Rondo in B minor (“Rondo brillant”) which opens regally and proceeds to a blend of jaunty upward leaps, inviting melodies, and coloratura flights of fancy.

Paul Lewis (above, in a Pia Johnson photo)

Following the interval, each artist took a solo turn. Mr. Lewis’s rendering of the Busoni arrangement of Bach’s Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland was profoundly beautiful in its grace and simplicity. Ms. Batiashvili played Telemann’s Fantaisie No. 4 in D major, its classic three-movement (fast-slow-fast) structure compressed into a five-minute time span, a miniature solo-concerto which was handsomely played.

The Beethoven sonata No. 10, which closed the evening, begins gently with shimmering trills; a simple two-note motif later in the first movement has a hypnotic quality, then back to a trill-filled conclusion before we move on to the achingly gorgeous, sustained melodies of the Adagio espressivo: here Ms. Batiashvili and Mr. Lewis were at their most ravishing. There’s no pause as the Adagio yields immediately to the brief, playful Scherzo with both players spinning the music onward. The fourth movement, Poco allegretto, seems calm at first but there’s underlying tension building: you can sense an impending flood of energy and surely enough it bursts forth. Both players were on a high here, yet cunningly the composer draws back into a lulling, rather sentimental passage. What then seems like a race to the finish gets momentarily sidetracked again – Beethoven is playing with us – before the last sprint.

Superb music-making in a most congenial space: we left Ms. Batiashvili and Mr. Lewis basking in the warmth of the audience’s cheers and applause.

The Program:

Schubert: Violin Sonata in A major

Schubert: Rondo in B minor (“Rondo brillant”)

Bach (arr. Busoni): Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland, for piano

Telemann: Fantaisie No. 4 in D major, for solo violin

Beethoven: Violin Sonata No. 10 in G major

-

IOLANTA/BLUEBEARD’S CASTLE @ The Met

Above: Boris Kudlicka’s set design for The Met’s production of Bartok’s BLUEBEARD’S CASTLE

Wednesday February 18th, 2015 – This pairing of ‘short’ operas by Tchaikovsky and Bartok at The Met didn’t really work. IOLANTA is an awkward work: too short to stand alone but too long to be successfully coupled with another opera. BLUEBEARD, so intense musically and rather static dramatically, is best paired with something like Schoenberg’s ERWARTUNG or Stravinsky’s OEDIPUS REX. Aside from the musical mismatch, the evening was further spoilt by an endless intermission.

Tchaikovsky’s IOLANTA is full of nice melodies and is perfectly palatable but at no point do we feel connected to the story or the characters as we do with ONEGIN or PIQUE-DAME. The production is gloomy, with a central ‘box’ (Iolanta’s bedroom) which periodically (and rather annoyingly) rotates. The stage direction was random and incoherent, the minor characters popping in and out, and then a big choral finale populated by men in waiters’ aprons. Nothing made much sense, really.

Musically, IOLANTA was given a not-very-inspired reading by Pavel Smelkov. It took Anna Netrebko a while to warm up; her singing became more persuasive as the evening wore on. She was attractive to watch and did what she could dramatically with a limited character and a dreary production. Mzia Nioradze was a sturdily-sung Marta. Among the male roles, Matt Boehler stood out vocally as Bertrand. Neither Vladimir Chmelo (Ibn-Hakia) nor Alexei Tanovitski (King Rene) seemed to be Met-caliber singers, and Maxim Aniskin’s Duke Robert was pleasant enough vocally though of smallish scale in the big House.

IOLANTA was in fact only saved by a superb performance as Vaudemont by Piotr Beczala. From the moment of his first entrance, the tenor’s generous and appealing sound and his commanding stage presence lifted the clouds of tedious mediocrity that had settled over the scene. As his most Gedda-like vocally, Beczala seemed to enflame Ms. Netrebko and their big duet had a fine sense of triumph.

The House, which was quite full for the Tchaikovsky, thinned out a bit at intermission. Those who stayed for the Bartok were treated to an impressive musical performance thwarted to an extent by busy, awkward staging. Mr. Smelkov seemed more in his element here than in the Tchaikovsky; the orchestra played Bartok’s gorgeous score for all it’s worth, and that’s saying a lot.

After the eerie, ominous spoken prologue, we enter Bluebeard’s dark domain. Where we should see seven doors, we instead see an automatic garage door closing. Then begins the long conversation between Bluebeard and Judith which will end with her bound in permanent captivity with his other wives.

The staging did the two singers – Michaela Martens and Mikhail Petrenko – no favors; periodically they appeared – for no apparent reason – in an isolated ‘cupboard’ high up at extreme stage left while the central space was filled with the filmed image of a gaping elevator shaft (see photo at the top of this article). The opening of each each ‘door’ was staged as a series of odd vignettes. Nothing made much sense. The final scene was ugly and failed to project the sense of mystery that should hover over Judith’s fate.

Both Ms. Martens and Mr. Petrenko were on fine vocal form, and both brought unusual warmth and unexpected lyricism to much of their music. They sang powerfully, the mezzo showing a large and expressive middle register and resonant lower notes, with the basso having both power and tonal beauty at his command.

At several points along the way, their singing seemed somewhat compromised by the staging; and never more so than in Judith’s famous high-C. At this moment, the director placed the singer far upstage – almost on Amsterdam Avenue – and so although Ms. Martens nailed the note, she was too far back to crest the orchestra. I suspect it was staged this way as a covering device for the vocal unreliability of the production’s earlier Judith, Nadja Michael.

But overall, Ms. Martens and Mr. Petrenko each made a distinctive vocal showing; and it was they, the Met orchestra, and Piotr Beczala’s Vaudemont earlier in the performance that gave the evening its lustre and saved it from sinking into the murky depths. Attempts to show some kind of link between the two operas by means of certain stage effects proved unconvincing. The Bartok, especially, deserves so much better.

Metropolitan Opera House

February 18, 2015IOLANTA

P I TchaikovskyIolanta....................Anna Netrebko

Vaudémont..................Piotr Beczala

Robert.....................Maxim Aniskin

King René..................Alexei Tanovitski

Bertrand...................Matt Boehler

Alméric....................Keith Jameson

Ibn-Hakia..................Vladimir Chmelo

Marta......................Mzia Nioradze

Brigitte...................Katherine Whyte

Laura......................Cassandra Zoé VelascoBLUEBEARD'S CASTLE

Béla BartókJudith.....................Michaela Martens

Bluebeard..................Mikhail PetrenkoConductor..................Pavel Smelkov -

LA BOHEME @ The Met

Monday Jaunary 19th, 2015 – When my friend Lisette was appearing in WERTHER at The Met in 2014, she spoke well of the tenor Jean-François Borras (above) who was covering the title-role and who ended up singing one performance. Now he is back for three performances as Rodolfo in LA BOHEME and I decided to try it, especially after some soprano-shuffling brought Marina Rebeka into the line-up as Musetta.

Overall it was a good BOHEME, though somewhat compromised by the conducting of Riccardo Frizza who had fine ideas about tempo and some nice detailing but tended to give too much volume at the climaxes: this might have worked had the principals been Tebaldi and Tucker, but not for the current pair of lovers. Mr. Borras wisely tried to resist pushing his voice; Kristine Opolais, the Mimi, was having other problems so riding the orchestra was the least of her worries. It was Ms. Rebeka who ended up giving the evening’s most stimulating performance, along wth baritone Mariusz Kwiecien, an outstanding Marcello.

Following her well-received Met RONDINEs, Ms. Opolais became something of the darling of The Met, especially when – last season – she sang back-to-back performances of Butterfly and Mimi. I heard one of the Butterflies which was marred by some sharpness of pitch. A glance at her bio reveals that she has already sung roles like Tosca, Manon Lescaut, Shostakovich’s Lady Macbeth, Jenufa, even Aida, all of which seem to me ill-suited to what is essentially a lyric voice. Tonight much of her singing was tremulous and pallid, and the tendency to go sharp spoiled several potentially attractive passages. One hears that The Met plans new productions of MANON LESCAUT, RUSALKA, and TOSCA for her (there are even whispers of a new THAIS); unless she can somehow repair her over-spent voice, I can’t see how she’ll get thru these demanding roles in the Big House. Anyway, she seems now to have been usurped as the talk-of-the-town soprano by Sonya Yoncheva…one wonders what new productions she has been promised. Meanwhile it’s sad to hear Ms. Opolais – who might be (have been?) a lovely Pamina, Liu, and Micaela – having pushed herself into inappropriate repertory at the cost of vocal stability.

Mr. Borras gave such an appealing performance that the conductor’s lack of consideration was particularly unfortunate. The tenor’s warm timbre falls most pleasingly on the ear, and he had so many felicitious phrases to give us, and some lovely word-colourings. After the orchestra encroached on the climax of “Che gelida manina” – which the tenor managed nonetheless – I enjoyed the way he handled Rodolfo’s little melodic gems at Cafe Momus, and his persuasive vocalism in Act III was a balm to the ear, especially the lingering bitter-sweetness of his hushed “…stagione dei fiori…”

Ms. Rebeka (above) was the most marvelous Musetta I have encountered since Carol Neblett’s sensational debut at New York City Opera in 1969. Her voice gleaming and generous, Ms. Rebeka seized the stage in no uncertain terms, really making something out of the super-familiar Waltz which she climaxed with a smile-inducing diminuendo on the top-B. She went on to thrill the ear in the ensuing ensemble, and she was excellent in Act III.

Mr. Kwiecien gave a first-rate performance as Marcello. In this music, he can spend his voice generously without having to be concerned with sustaining a full title-character evening, something he’s never had quite the vocal and theatrical presence for, despite his undoubted appeal. Tonight, it was ample-toned, warm singing from note one, and an extroverted, somewhat ‘mad-artist’ view of the character handsomely presented. Would that he’d had a Mimi to match him in the Act III duet. But he and Borras were both superb in their scene, in which they almost came to fisticuffs before Rodolfo finally admitted the truth about Mimi’s illness and his hopeless state of poverty. Kwiecien then melted into the caring ‘best friend’ that makes Marcello a standout portrait in these scènes de la vie de bohème.

Alessio Arduini (Schaunard) and David Soar (Colline) gave attractive vocal performances despite the conductor’s trampling on some of their lines; they were charming during a mini-food-fight at Cafe Momus.

Some of the staging at the Barrière d’Enfer didn’t enhance the narrative: Mimi reveals her eavesdropping presence not by an attack of coughing – such a moving device – but by stumbling down the staircase and collapsing melodramatcally at the door to the inn. Later, too many by-standers surround Marcello and Musetta as they argue, and the ever-so-moving reconciliation of Mimi and Rodolfo is marred by Musetta grabbing a passser-by and kissing him lavishly: this gets a wave of unwanted laughter during one of the opera’s most poignant moments.

The first intermission was debilitating; these extended breaks always drain the life out of the evening, and the better the performance the more annoying they are. And seat-poaching is so unattractive, especially when it causes a disruption if there’s an unexpected seating break – as tonight between the garrett and Momus.

But BOHEME still casts its spell, as it has for me ever since I first heard it on a Texaco broadcast 53 years ago to the day, with Lucine Amara and Barry Morell as the lovers. The Beecham recording remains my touchstone document of this heart-rending score. Tonight’s audience, quite substantial by current standards, embraced the classic Met production warmly.

Metropolitan Opera House

January 19th, 2015LA BOHÈME

Giacomo PucciniMimì....................Kristine Opolais

Rodolfo.................Jean-François Borras

Musetta.................Marina Rebeka

Marcello................Mariusz Kwiecien

Schaunard...............Alessio Arduini

Colline.................David Soar

Benoit..................John Del Carlo

Alcindoro...............John Del Carlo

Parpignol...............Daniel Clark Smith

Sergeant................Jason Hendrix

Officer.................Joseph TuriConductor...............Riccardo Frizza