Wagnerian afternoons in the Summer: from the Bayreuth Festival 1961 comes the prologue and first act of GOTTERDAMMERUNG featuring Birgit Nilsson at her most marvelous. Conducted by Rudolf Kempe, the performance generates tremendous excitement, most notably in the thrilling build-up to the Dawn Duet. Nilsson unleashes her patented lightning-bolt top notes, and hearing her on this form reminds me of my first encounters with her live at The Met where in 1966 she sang a series of Turandots that were simply electrifying.

The performance is very fine all around, opening with a thoroughly absorbing Norn Scene which begins with the richly expressive singing of contralto Elisabeth Schärtel (above) followed soon after by the equally impressive Grace Hoffman. It’s rather surprising to find Regine Crespin singing the Third Norn. She had made a huge success at Bayreuth in 1958 as Kundry, and had repeated that role at the next two festivals. In 1961 she was invited back to the Green Hill for Sieglinde, and thus she was able to take on the Norn as part of her summer engagement. She sings beautifully, with her distinctive timbre, though there is a trace of tension in her highest notes.

Above: Birgit Nilsson; we used to refer to her as “The Great White Goddess” or simply “The Big B”. The thrilling accuracy and power of her singing here, as well as her ability to create a character thru vocal means, is breath-taking.

Hans Hopf is a fine match for Nilsson in the Dawn Duet; he is less persuasive later on when his singing seems a bit casual. Wilma Schmidt (Gutrune) and the always-excellent Thomas Stewart (Gunther) make vocally strong Gibichungs, and the great Wagnerian basso Gottlob Frick is a dark-toned Hagen with vivid sense of duplicity and menace. Rudolf Kempe again shows why he must be rated very high among the all-time great Wagner conductors: his sense of grandeur and ideal pacing set him in the highest echelon.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Gerhard Stolze (above) is the Loge in a RHEINGOLD from the Bayreuth Festival 1964; I have a special love for Mr. Stolze in this role as he was my first Loge – at The Met on February 22, 1968, a broadcast performance conducted by Herbert von Karajan and my first experience of a RING opera live. Here at Bayreuth, as later at The Met, Stolze brings a wonderfully debauched, almost greasy vocal quality to the vain, spoiled demi-god. The voice is large and effortlessly penetrating, but he can also be tremendously subtle: after screaming “Durch raub!’ (‘By theft!”) when Wotan asks Loge how the Rhinegold might be acquired, Stoltze goes all lyrical as he says: “What a thief stole may be stolen from the thief…” this is but one of Stotze’s countless brilliant passages in the course of his portrayal. At Nibelheim and later, as Loge taunts the captured Alberich, Stolze is simply superb.

Two other singers who appeared in my Met/Karajan RHEINGOLD are also heard in this Bayreuth performance: Theo Adam has a big, burly voice and sings imposingly if not always with a lot of tonal allure. His Wotan builds steadily throughout the opera to an imposing rendering of Wotan’s greeting to Valhalla and the entire final scene. Zoltán Kelemen is a splendid Alberich; his handsome baritone sound sometimes shines thru in what is essentially a dramatic character role. Power and calculation mark his traversal of the first scene; later, in Nibelheim, Kelemen is wonderfully subtle. Having been tricked by Loge and kidnapped, he’s truly fabulous as he summons his slaves to bring the treasure up as ransom for his freedom. Later, having lost everything, his crushing sense of vulnerability gives way to a violent hurling of the curse at Wotan.

Above: Zoltán Kelemen as Alberich

Grace Hoffman is a capital Fricka, bringing verbal urgency and vocal attractiveness to her every line, most expressive as she draws Wotan back to her after Erda’s intervention. Jutta Meyfarth, a very interesting Sieglinde on the 1963 Bayreuth WALKURE conducted by Rudolf Kempe, is too stentorian and overpowering as Freia, a role which – for all its desperation – needs lyricism to really convince. Hans Hopf, ever a stalwart heldentenor, probably should not have tried Froh at this point in his career: he sounds too mature. Marcel Cordes is a muscular-sounding Donner; there is an enormous thunderclap to punctuate Donner’s “Heda! Hedo!”

The estimable contralto Marga Höffgen brings a real sense of mystery to Erda’s warning. Gottlob Frick is a vocally impressive Fasolt, his scene of despair at giving up Freia is genuinely awesome. Peter Roth-Ehrang (Fafner) and Erich Klaus (Mime) are names quite unknown to me; the basso is a bit blustery but has the right feeling of loutishness. Herr Klaus is a first-class Mime, with his doleful singing in the Nibelheim scene giving way to a fine mix of dreamy dementia and raw power as he tells Loga and Wotan of his dwarvish despair. Barbara Holt as Woglinde plucks some high notes out of the air; Elisabeth Schwarzenberg and the excellent Sieglinde Wagner as her sister Rhinemaidens.

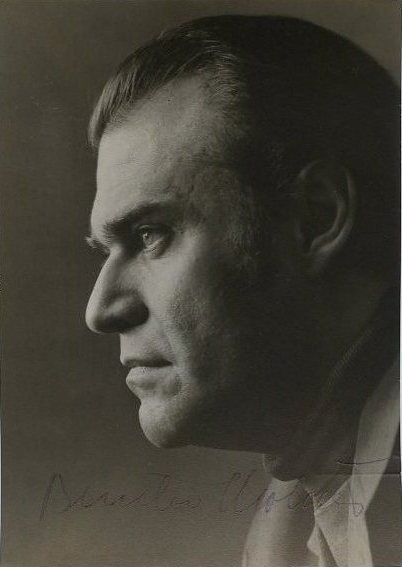

Berislav Klobucar (above), who conducted 21 Wagner performances at The Met in 1968 (including taking over WALKURE from Herbert von Karajan when the latter withdrew from his half-finished RING Cycle for The Met) opens this RHEINGOLD with a turbulent prelude. Klobucar has an excellent feel for the span of the opera, for the intimacy of the conversational scenes, and for the sheer splendour of the opera’s finale.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Above: a Günther Schneider-Siemssen design for the Herbert von Karajan Salzburg Festival production of the RING Cycle, 1967.

Thinking of my Karajan/RHEINGOLD introduction to the RING at The Met in 1968 caused me to next take up the conductor-director’s complete WALKURE and GOTTERDAMMERUNG from the 1967 Salzburg Festival where his production of the Cycle originated. Of course, he only ended up conducting RHEINGOLD and WALKURE at The Met though the two remaining operas were staged there in his absence, with the productions credited to him. The settings remained in use at The Met thru 1981, and then the Otto Schenk production commenced in 1986.

I must admit to never having listened to Karajan’s commercial RING Cycle (maybe a few random scenes but never any of the complete operas); it’s simply one of those inexplicable sins of omission which all opera lovers must eventually confess to. Maybe someday I will get around to it, though I’m so taken up with all these live RING recordings that Opera Depot keep tempting us with.

At any rate, I must say I don’t much care for Karajan’s first act of WALKURE, at least not as it was performed at Salzburg in 1967. It feels to me terribly slow and overly polite. Gundula Janowitz and Jon Vickers seem much of the time to be vocally walking on eggshells: they whisper and croon gently to one another and the lifeblood seems to drain out of the music. Martti Talvela is his usual excellent self as Hunding; once he has gone to bed, Vickers commences a properly reflective sword monologue (the first orchestral interjection of the Sword motif ends on a cracked note). The tenor is stunning in his prolonged cries of “Wälse! Wälse!”, and then comes Janowitz’s ” Der Männer Sippe” which is verbally alert but there’s a slight tension in her upper notes and a feeling of being a bit over-parted. They sing very successfully thru the familiar “Winterstürme” and “Du bust der Lenz” all filled with attractive vocalism but Karajan maintains a rather stately pacing thru to end end of the act: there’s no impetus, no sense of being overwhelmed by sexual desire. Actually I found it all somewhat boring, and my mind tended to wander.

A complete volte face for Act II, one of the finest renderings of this long and powerful act that I have ever encountered. Karajan launches the prelude, weaving together the various motifs, and Thomas Stewart unfurls Wotan’s opening lines commandingly. Regine Crespin’s sings a spirited “Ho-Jo-To-Ho!” and then Fricka arrives on the scene…

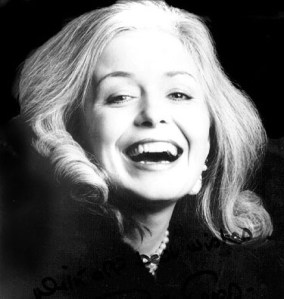

…in the marvelous person of Christa Ludwig (Louis Melançon photo, above). When people ask me, “Who was the greatest singer you ever heard?” I invariably reply “Christa Ludwig” even though on a given day the memory of some other voice might seem to rival her. But in everything I have heard from her, both live and on recordings, Ludwig seems to have the ideal combination of a highly personal timbre, natural and effortless technical command, a remarkably even range, phenomenal abilities as a word-colorist, and overwhelming warmth and beauty of sound. Her Fricka here is magnificent in every way, and so supremely Christa.

The scene between Fricka and Wotan is so impressive, yet incredibly Thomas Stewart (above, with Karajan) goes on to surpass himself with one of the most thrilling and spine-tingling renderings of Wotan’s monolog that I have ever experienced. Stewart vocally displays every nuance of the god’s emotional state as he confides in his daughter, first in his long ‘historical’ narrative which grumbles and whispers its way into our consciousness. Crespin is an ideal listener, her beauteously sung queries lead her father to divulge more and more. Soon Stewart is pouring out both his vanity and despair; the temperature is at the boiling point when he reaches “Das ende! Das ende!”, overcome by tears of anguish. Instructing Brunnhilde to honor Fricka’s cause and defend Hunding in the impending fight, Stewart crushes Crespin’s protests with a furiously yelled “Siegmund falle!” (“Siegmund must die! That is the Valkyrie’s task!”) and he storms away. I had to stop at this point; Stewart’s performance had both moved and shaken me and I wanted to pause and reflect.

As beautifully as Crespin and Vickers sing the ‘Todesverkundigung’ (Annunciation of Death), the scene does not quite generate the mysterious atmosphere that I want to experience here. Thomas Stewart’s snarling “Geh!” as he send Hunding to his fate is a fabulous exclamation mark to end the act.

Act III opens and there is some very erractic singing from the Valkyries in terms of pitch and verbal clarity. Crespin’s top betrays a sense of effort in her scene with Sieglinde, and Janowitz’s voice doesn’t really bloom in Sieglinde’s ecstatic cry ” O hehrstes Wunder!” Thomas Stewart hurls bold vocal thunderbolts about as he lets his anger pour out on Brunnhilde and her sisters.

And then at last the stage is cleared for the great father-daughter final scene. Crespin is at her very best here, singing mid-range for the most part and with some really exquisite, expressive piano passages. Only near the end, when the music takes her higher, does the tendency to flatness on the upper notes seem to intrude. Stewart is impressive throughout. Karajan takes the scene a bit on the slow side, but it works quite well.

It should be noted that the voice of the prompter sometimes is heard on this recording, especially in Act I.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Above: Karl Ridderbusch, who sang Hagen in the 1967 Salzburg Festival RING Cycle.

Herbert von Karajan’s GOTERDAMMERUNG, from the Salzburg Festival 1970, starts off with a very fine Norn Scene. Lili Chookasian – after a few warm-up measures – and Caterina Ligendza are authetically Wagnerian as the first and third sisters, with the resplendent Christa Ludwig luxuriously cast as the 2nd Norn. Her superb vocalism is marked by a great lieder-singer’s colourings of the text.

Helga Dernesch and Jess Thomas give a sturdily-sung rendition of the Dawn duet. Though Dernesch’s highest notes seem somewhat tense, she does sustain a solid high-C at the duet’s conclusion. Karl Ridderbusch is a potent Hagen, able to bring out a softer grain to the tone when he wants to. His sound is somewhat baritonal, but he still hits the lowest notes with authority. Thomas Stewart is an outstanding Gunther, a role that often loses face as the opera progresses. Gundula Janowitz is not my idea of a good Gutune: she sound mature and a bit tired.

Christa Ludwig’s Waltraute is a performance of the highest calibre; her superb musicality wedded to her acute attentiveness to the words make this scene the highlight of the performance. Dernesch is good here also, but both she and Jess Thomas seem to flag a bit in vocal energy in the rape scene.

Act II opens with another of my favorite RING scenes: Alberich (Zoltán Kelemen) appears to his son Hagen (Karl Ridderbusch). Kelemen, so musical in the 1964 Klobucar RHEINGOLD reviewed above, here resorts to sprechstimme and all manner of vocal ‘effects’: I wonder if this is what Karajan wanted, or is this simply what the baritone came up with. Ridderbush sings much of Hagen’s music here in an appropriately dreamy half-voice. A bit later he turns on the power with his “Hoi ho!”, summoning the vassals; the men’s chorus lung it lustily in response. Despite the continued feeling of effort behind Helga Dernesch’s high notes, she hits them and holds them fair and square. Jess Thomas sounds a bit tired as Siegfried; though he manages everything without any slip-ups, the voice just seems rather weary. Gundula Janowitz’s Gutrune is much better in Act II than earlier in Act I, and Thomas Stewart’s Gunther transforms what is sometimes viewed as a ‘secondary’ role into a major vocal force in this performance.

I had high hopes for the opening scene of Act III: the Rhinemaidens – Liselotte Rebmann, Edda Moser, and Anna Reynolds are all fine singers. Yet they don’t quite achieve a pleasing blend. Jess Thomas sounds brassy and one keeps thinking he might have a vocal collapse, but he stays the course. It is left to Dernesch to be the performance’s saving grace and she nearly accomplishes it: the sense of vocal strain is successfully masked for the most part and she hits and sustains the high notes successfully though it’s clear she is happier singing lower down; she did in fact become a highly successful dramatic mezzo in time. Dernesch gives the Immolation Scene a tragic dimension, and then Karajan sweeps thru the long orchestral postlude with a sense of epic grandeur.

Overall, Karajan’s GOTTERDAMMERUNG is impressive to hear. Were Helga Dernesch and Jess Thomas thoroughly at ease vocally the overall performance would have been quite spectacular. As it is, it’s Christa Ludwig, Thomas Stewart, and Karl Ridderbusch who make this a memorable Twilight of the Gods.