Note: this article has been written over the course of several months

Four recordings of live performances of Wagner’s LOHENGRIN have come my way, courtesy of my friend Dmitry. Despite being rather busier during this Summer of 2013 than I’d anticipated, I found time on these hot afternoons to start listening to these performances, an act at a time. Invariably I’ll listen to the same act two or three times, so as not to miss anything.

LOHENGRIN might be considered Wagner’s most beautiful opera; from the ethereal opening bars of the prelude, it weaves a spell of mystery, romance, and deceit all under-scored by the Dark Arts. Marvelous stretches of melodic splendor – Elsa’s Song to the Breezes (“Euch luften“), the bridal procession to the cathedral, Lohengrin’s tragically tender “In fernam land” – mix with ‘greatest hits’ like the über-familiar Wedding March and the thrilling Act III prelude. Three prolonged duets are the setting for major dramatic developments in the narrative: Ortrud and the banished Telramund outside the city walls; Elsa meeting with and being beguiled by Ortrud; and Elsa and Lohengrin on their bridal night where the hapless girl asks the fatal question. King Henry has his orotund prayer “Mein Herr und Gott!” whilst Ortrud calls upon the forsaken pagan gods in her great invocation “Entweihte Götter!” The conflict between darkness and light is manifested in the great confrontation between Ortrud and Elsa on the cathedral steps, the violins churning away feverishly as the two voices vie for the upper hand; Ortrud has the last word.

So it’s an opera that is easy to listen to repeatedly; and the more you listen, the more you hear…yes, even after 50+ years of getting drunk on Wagner, I still discover new things in his operas.

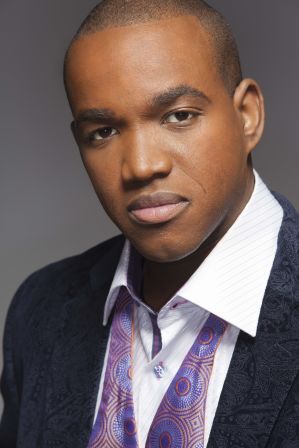

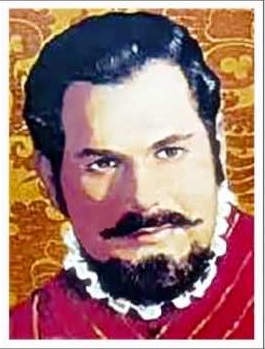

Jess Thomas (above) is the Lohengrin on two of these recordings, the first from Munich 1964 and the second from Vienna 1965. I listened to the Munich first, conducted by Joseph Keilberth, and found it a strong, extroverted performance. None of the principal singers go in for much subtlety, instead flexing their Wagnerian vocal muscles in generous style.

Keilberth’s conducting has sweep and intensity, though perhaps lacking a bit of the dreamlike quality that can illuminate the more spiritual passages of the opera. This accords well with the singing, since neither Jess Thomas nor his Elsa, Ingrid Bjoner, use much dynamic contrast (though when they do it works wonders). Both have big, generous voices and they are on fine form for this performance.

Jess Thomas was my first Calaf (at the Old Met), Siegfried, Tristan and Parsifal. He was a mainstay at The Met in the helden roles from 1962 to 1982, returning in 1983 to sing part of Act I of WALKURE with Jessye Norman for the Met’s 100th birthday gala. His is not the most gorgeous sound imaginable but his power and security are amply in evidence in this Munich performance.

Above photo: Ingrid Bjoner in GOTTERDAMMERUNG, with tenor Jean Cox

I’ve always liked Ingrid Bjoner; her rather metallic sound and steely top served her well in a long Wagnerian career. I only saw her onstage once – as Turandot, a memorable performance both from a vocal and dramatic standpoint. In this Munich LOHENGRIN, Bjoner sails thru the music with exciting vocal security. If only rarely does she engage in the floating piani that many sopranos like to display in this music (the end of Bjoner’s ‘Euch luften’ is ravishing!), hers is an impressive reading of the music.

In a thrilling performance, Hans Günther Nöcker turns the sometimes-overshadowed role of Telramund into a star part. His narration of the shame and degradation he feels at having been bested in the duel and then exiled is a powerful opening for the opera’s second act.

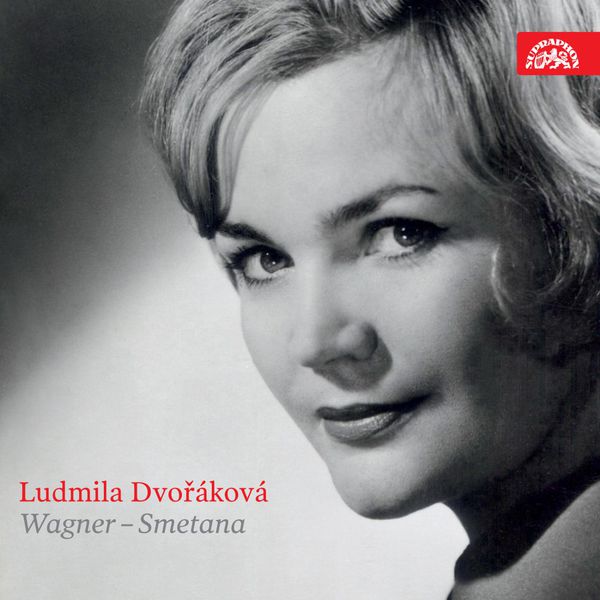

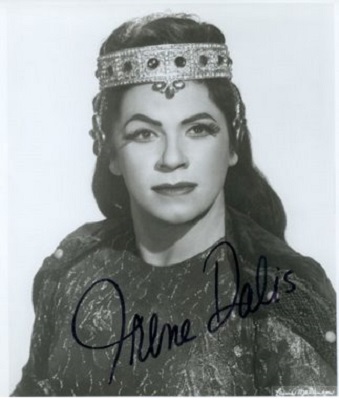

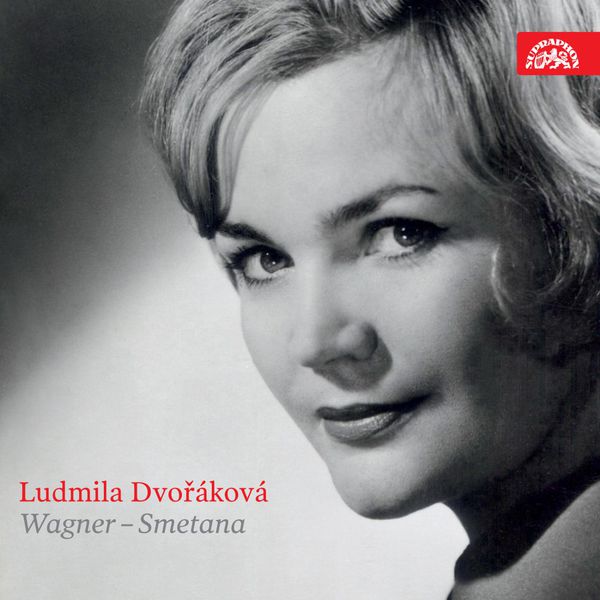

Ludmila Dvorakova’s large, somewhat unwieldy voice has ample thrusting power for Ortrud’s great invocation in Act II, though she tends to leave off clear enunciation of the text in favor of simply pouring out the sound. Dvorakova (above) – who sang Isolde, Leonore and Ortrud at the Met in the 1960s – was known for her magnetic stage presence.

Gottlob Frick is a powerful Henry, but there’s a question as to whether it’s Josef Metternich or Gerd Neinstedt as the Herald in this performance – whoever it is, he is not having his happiest night vocally.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

When in 1966 tenor Nicolai Gedda was announced for performances of Lohengrin in Stockholm, there was some hand-wringing among the fans. Gedda was known for his stylish lyricism and easy top in the bel canto and French repertoire; he had tackled such high-flying roles as Arturo in PURITANI and Raoul in HUGUENOTS with striking command. By venturing into Wagner, Gedda was thought to be putting his instrument at risk. But he sang Lohengrin on his own terms, with true-tenor (rather than baritonal) timbre, producing one beautiful phrase after another. The recording, which I owned on reel-to-reel at the time it was first available, is a valuable document since Gedda never again sang the role, nor any other Wagnerian role, onstage.

Gedda in fact is one of the most pleasing Lohengrins to hear; as in another mythic/heroic role he tackled only once – Aeneas in TROYENS – the tenor’s clarity of both tone and diction – and his complete ease when the vocal line goes upward – mark his performances in these operas as ideal, even though they both quickly fell out of his active repertory.

Gedda was my first Nemorino (at the Old Met) and I saw him many times over the ensuing years (as Don Jose, Don Ottavio, Elvino, Edgardo, Faust and Lensky), always impressive in his artistry and vocal security. Far from ruining his voice, the Lohengrin simply served as a vocal adventure for the tenor; he went on singing for another 20 years after portraying the mysterious knight. His Met career spanned 25 years and nearly 375 performances, including singing the final trio from FAUST at the very last performance at the Old Met.

Aside from Gedda, this Stockholm LOHENGRIN is very enjoyable in many ways though not quite reaching the mystical heights that some performances of this opera have attained. Conductor Silvio Varviso has a fine sense of pacing and if the orchestral playing is not world-class, a lyrical atmosphere develops nicely right from the start.

I’m particularly taken with the performances by the two female leads: the Norwegian soprano Aase Nordmo Løvberg (above) makes a distinctive impression as Elsa; her voice, rather Mozartean in heft and feeling, has clear lyrical power and expresses the character’s vulnerability well. The soprano appeared at The Met 1959-60 as Elsa, Eva, Sieglinde and Leonore; she passed away earlier this year, one of those ‘forgotten’ voices still held dear by a diminishing group of aficianados who listen to older recordings.

As Ortrud, Barbro Ericson (above) gives a blazing performance. Like Nordmo Løvberg, Ericson did sing at The Met (1967-68): she was Siegrune in the ‘Karajan’ WALKURE performances, and stepped in once as Fricka; she returned a decade later to sing Herodias in SALOME with Grace Bumbry as her daughter. Ericson was a fearless singer with a rich chest voice and some stunningly easy top notes.

As King Henry, Aage Haugland’s sturdy and humane bass sound is a big asset in the Stockholm LOHENGRIN; Rolf Jupither is a solid Telramund and Ingvar Wixell – who went on to be a major Verdi baritone (he was a wonderful Boccanegra at the Met in 1973-74) – already shows vocal distinction as the Herald.

in the third act, this performance is particularly gratifying, for Ms. Nordmo Løvberg and Mr. Gedda sing one of the most lyrical and polished versions of the Bridal Chamber duet that I’ve ever heard. And the tenor is absolutely splendid in the long narrative “In fernem land” and his tender farewell address to his wife; with poetic expression tinged in sadness, he presents Elsa with the horn, sword and ring that are meant for her lost brother, Gottfried. Gedda’s anguished “Leb wohl!” to his distraught bride is like an arrow to the heart. This document of Gedda’s performance, capped by his magnificent vocalism in the opera’s final twenty minutes, can be considered a treasured rarity in the annals of great Wagner singing.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

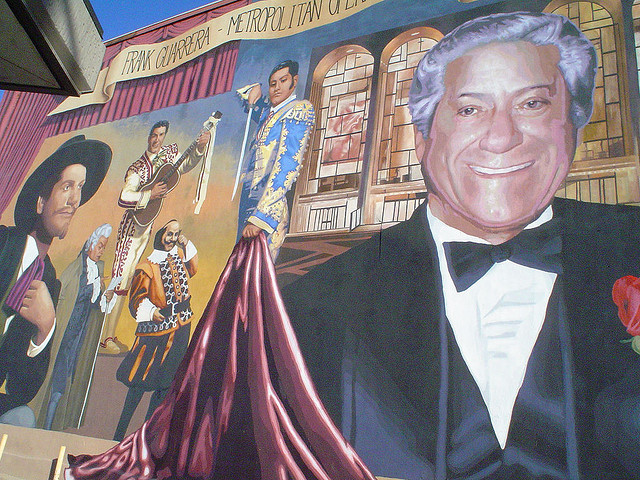

Above: tenor René Maison

As Summer 2013 ended and the performance season started up, I had less time to devote to listening at home; and so it wasn’t until the dark, chilled days of February 2014 that I took up a rarity: 1936 LOHENGRIN from Buenos Aires which features René Maison, Germaine Hoerner, Marjorie Lawrence, Fred Destal, Alexander Kipnis, and Fritz Krenn, with Fritz Busch on the podium. Of the singers, Hoerner, Destal, and Krenn were names I’d never even heard of prior to settling down with this recording.

Germaine Hoerner was born in Strasbourg in 1905, made her debut at L’Opera de Paris in 1929 and sang such roles as Elsa, Gutrune, Senta (photo above), Aida, Desdemona, the Marschallin, and Beethoven’s Leonore during her career which lasted thirty years. How strange that I’d never encountered her voice before.

Fred Destal began his career as a choirboy in Liegnitz and sang professionally at the Deutsches Theater in Brünn, before joining the Deutsches Opernhaus (later the Städtisches Oper) in Berlin. In 1933 he left Germany for the Zurich Opera. He sang at the Vienna State Opera from 1936–1938, and emigrated to the United States in 1938. He made many guest appearances in Europe and frequently performed at the Colón in Buenos Aires where he essayed several Wagnerian roles as well as singing in operas by Mozart and Strauss, and in operetta.

Fritz Krenn debuted in 1917, singing with the Vienna State Opera from 1920-1925 and the State Opera, Berlin, from 1927 til 1943. He became celebrated for his Baron Ochs, singing the role over 400 times including seven performances at The Met in 1950. He died in 1963.

The three other leading artists in this 1936 Buenos Aires LOHENGRIN all had major careers – Marjorie Lawrence’s unfortunately much altered by the onset of polio in 1941. Though her legs were paralyzed, she returned to the stage in 1943, singing performances of Venus and Isolde at The Met from a seated position; but the wife of a Metropolitan Opera board member was put off by the sight of the disabled soprano onstage and her Met career ended. Lawrence’s life was the subject of a 1955 film, Interrupted Melody.

The sound quality on this 1936 performance – needless to say – is very uneven; yet not enough so to deter the adventuruous listener. Passages where the volume fades come and go, and these sometimes occur at exactly the “wrong” moment. But there’s enough acceptable sonic accessability to have a pretty good idea of what the performance was like.

Fritz Busch conducts and, though the orchestra playing (and the recording of it) leave something to be desired, the conductor establishes the dramatic atmosphere right from the start of the celestial prelude – a prelude which draws unexpected and sustained applause from the audience.

Alexander Kipnis sounds somewhat unsettled in this performance as King Henry: his career had already lasted 20 years and The Met was still in his future. He may have suffered from the recording techniques employed or simply have been having an off-night. Here are no serious flaws in his singing, but surely he’s not as his best. Germaine Hoerner has a brightish voice with a slight flutter that gives her singing an almost girlish attractiveness and a vulnerable appeal – quite nice for this role. There are some vague pitch issues but she does make an impression right from her opening line. René Maison sings expressively as Lohengrin, with a good feel for the other-worldly yet heroic quality the music calls for; he shows impressive dynamic control from the start. Fritz Krenn begins rather anonymously as the Herald but gains ground as Act I progresses. Fred Destal’s Telramund is dramatically vivid in the opening act – his greatest moments lie ahead – and Ms. Lawrence makes only the briefest vocal appearance in Act I.

Despite the lack of immediacy in the sound quality, Busch opens Act II with a good sense of impending doom; in the duet for Ortrud and Telramund, Lawrence and Destal are appropriately gloomy. Later Ms. Lawrence is ever-so-slighly taxed by some of Ortrud’s highest notes but she’s very exciting at “Zurück, Elsa!” and the whole of their confrontation is well done. Destal’s attempt to incite the knights is another good passage, and Fritz Krenn’s singing as the Herald is more vivid than in Act I. Busch takes the wedding procession music rather faster than we often hear it, and the chorus sound a bit daunted at this point. What sets this second act on a higher plane is the singing of Hoerner and Maison: the soprano’s voice, now at full sail, is full of lyrical grace; her pitch is now steady and the voice takes on a silvery gleam in the upper range. Maison’s tenderness towards Elsa is lovingly expressed, and Ms. Hoerner responds to his reassurance with a finely-turned rendering of the marvelous passage “Mein Retter, der mir Heil gebracht! Mein Held, in dem ich muss vergehn, hoch über alles Zweifels Macht soll meine Liebe stehn.” (“My deliverer, who brought me salvation! My knight, in whom I must melt away! High above the force of all doubt shall my love stand.”)

After a brisk prelude, Act III begins with the chorus of the bridal party approaching; the antique sound quality gives the voices a ghostly air, and as they recede I was struck by the fact that it’s unlikely anyone who was at this performance is still alive today, and struck yet again that it has come to us from across a three-quarter-century span of time.

Ms. Hoerner and Mr. Maison achieve poetic vocal distinction in the Bridal Chamber duet; the tenor’s gentle ardor is movingly expressed with some lovely soft nuances and the soprano sounds girlishly enraptured; of course, their joy is short-lived as Elsa’s gnawing curiosity overwhelms her. As the opera moves to its inexorable end, Mr. Maison sings ‘In fernem land’ so movingly. Ms. Hoerner reacts to the imminent departure of her knight with frantic despair; but Ms. Lawrence is not comfortable in Ortrud’s final vengeful utterances: she sounds taxed and rather desperate. Mr. Maison then delivers the most extraordinary singing of the entire performance: at ‘Mein lieber schwan’ he pares down the voice to a mystic thread of tone, coloured with an amazing sense of weeping. I’ve never heard anything like it; it literally gave me the chills.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Then back to Jess Thomas for the Vienna 1965 performance. The tenor is perhaps a shade less commanding vocally than in the Munich/Keilberth performance, but impressive nevertheless.

For the Vienna ’65, Karl Bohm is on the podium, giving a refined delicacy to the prelude and showing a near-ideal sense of pacing and of the architecture of the work. Bohm underscores a sense of impending doom when – initially – no champion answers the calls to defend Elsa’s honor.

Claire Watson, the American soprano who never sang at The Met but was a beloved star at Munich for several years, sings Elsa with a nice aristocratic feel. The voice is clear and steady, with just a slight touch of remoteness that suits the character.

Walter Berry (Telramund) and Eberhard Waechter (the Herald), two of Vienna’s most beloved baritones at this point in time, are very fine in Act I; Martti Talvela’s sing as King Henry is at once powerful and humane. Talvela’s voice has a trace of a sob, and there are passing moments of off-pitch singing here and there but overall he is impressive.

And then we come to Act II…

Above: Christa Ludwig

From the moment of curtain-rise, the second act of this LOHENGRIN is simply thrilling. Not only is the singing of the principals at a very high level throughout, but the dramatic atmosphere that is generated raises the temperature to the boiling point very early on in the act and sustains it til the final omnious re-sounding of the Ortrud motif as Elsa and Lohengrin enter the cathedral.

It’s the divine Christa Ludwig and her then-husband Walter Berry who set this act on its magnificent trajectory. Outside the city walls, Mr. Berry, as Telramund, having been defeated in single combat by Elsa’s mysterious knight in shining armor, prepares to face his fate in exile: “Arise, companion of my shame!” he tells his wife. But Ortrud, as if in a trance, cannot comprehend their banishment. In his monolog of defeat, Telramund blames his wife for his predicament, ending his tirade with “Mein Ehr hab ich verloren!” (“I have lost my honor!”) Having sung this whole passage thrillingly, Mr. Berry dissolves in anguished sobbing. I’ve never heard this passage so powerfully delivered.

In the ensuing dialogue, as Ortrud tells Telramund how his fate can be reversed, both singers are incredibly alive to ever nuance of the music and text. In a searing moment, Telramund/Berry states that his defeat was an act of God; to this, Ortrud/Ludwig replies with a blistering, sustained “Gott????!!!!!” and then emits a ghastly laugh. Mr. Berry’s rejoinder marks another high point for the baritone; indeed both he and Ms. Ludwig continue throughout this scene to match one another in intensity and vocal splendour. Singing in doom-ladened unison, they conjure up a vision of revenge in “Der Rache Werk…”

Then Elsa appears on the high castle balcony: Miss Watson in fine lyric form for the Song to the Breezes. But Ortrud calls to her from out of the darkness and after a bit of servile groveling on Ortrud’s part, Elsa agrees to come down and speak with her wounded nemesis. Ms. Ludwig then lauches her hair-raising invocation of the ancient gods:

“Ye gods profaned! Help me now in my endeavor!

Punish the ignominy that you have suffered here!

Strengthen me in the service of your holy cause!

Destroy the vile delusions of those who deny you!

Wotan! I call on you, O god of strength!

Freia! Hear me, O exalted one!

Bless my deceit and hypocrisy,

that I may be successful in my revenge!”

This brilliant passage, delivered with stunning amplitude and soaring top notes by the inimitable Christa Ludwig, literally stops the show. The audience bursts into frantic appplause, a mid-act rarity in Wagner performances, and Maestro Bohm must wait several seconds to continue.

In their ensuing duet, Christa Ludwig uses the subtle finesse of a great lieder singer to worm her way into Elsa’s trust. Both Ludwig and Ms. Watson sing superbly here, with a perfect blend as their voices entwine. Elsa’s overwhelming goodness seems to have converted Ortrud: the orchestral melody of forgiveness and sisterhood – my favorite moment in the opera – signals false hope. In a devastating passage as Elsa draws Ortrud into the castle, Telramund emerges from the shadows and again Mr. Berry is pure magnificence in his closing statement:

“Thus misfortune enters that house!

Fulfil, O wife, what your cunning mind has devised;

I feel powerless to stop your work!

The misfortune began with my defeat,

now shall she fall who brought me to it!

Only one thing do I see before me, urging me on:

that he who robbed me of my honour shall die!”

As the scene ended I was literally stunned. It took me a couple of days before I could go on with the recording; I just wanted to savour what I’d heard. It’s such a great feeling to experience the pure exaltation of a genuinely exciting operatic performance – a feeling that is quite rare in this day and age – and know that the emotions are still there, waiting to rise to the surface.

But when I did take up the recording again, there were still more thrills in the second act: for one thing, Mr. Wachter as the Herald is on top form, and Mr. Berry continues his exciting performance as he tries to shore up support from some disgruntled comrades. The bridal procession commences, and Dr. Bohm begins the steady build-up to the fiery confrontation beween Elsa and Ortrud. As their vocal duel is engaged, the steadfast and true Ms. Watson sails confidently thru her phrases, bolstered by the populace. Cresting to a splendidly sustained top note, Elsa seems to be the victor but it’s Ortrud who has the final word: Christa Ludwig delivering a vocal knockout punch with dazzling self-assurance.

So: what a lot I have written about this second act! It’s truly one of the most fascinating listening experiences in my long operatic career. The opera goes on, of course, and the final act is perfectly pleasing in every regard. Claire Watson and Jess Thomas manifest their lyrical selves in the Bridal Chamber duet while the slow rise of panic is well under-lined by Dr. Bohm. Martti Talvela sings superbly in the opera’s final scene by the river bank, and Mr. Thomas has plenty in reserve for ‘In fernem land’, showing expert vocal control. Christa Ludwig is at her full and imperious best in Ortrud’s final vocal victory lap…but then she’s undone when Lohengrin magically produces Gottfried: Ms. Ludwig emits a devastating moan.

So, nearly nine months after I started writing this article, I’ve run out of LOHENGRINs to write about…at least for the moment.