Thursday March 23rd, 2023 – The American Symphony Orchestra performing Richard Strauss’s rarely-heard DAPHNE in concert form at Carnegie Hall, with Maestro Leon Botstein on the podium. The Bard Festival Chorale, under the direction of James Bagwell, had a big part to play in the proceedings.

The one-act opera, written in 1936-1937, comes late in Strauss’s composing career, when ELEKTRA, SALOME, ROSENKAVALIER, DIE FRAU OHNE SCHATTEN and ARIADNE AUF NAXOS were already established in the world’s opera houses.

The story of DAPHNE in a nutshell: Shepherds anticipate the feast of Dionysus, with Daphne’s parents, Peneios and Gaea, presiding over the preparations. Daphne, in love with nature, shuns the ways of men. Her childhood playmate, the shepherd Leukippos, tries to embrace her lovingly, but she repels him and renounces the coming festivities. She refuses to don the clothing her mother has lovingly prepared for her, and runs away. Playfully, the women persuade Leukippos to wear the clothes instead. Apollo arrives, in a peasant’s disguise, and is immediately drawn to Daphne, who rebuffs him. The feast begins, and the disguised Leukippos offers Daphne a cup of wine, arousing the jealousy of Apollo. The heavens respond to the god’s anger with rumbles of thunder, which cause the sheep to run away; the shepherds chase after the flock, leaving Apollo, Daphne, and Leukippos alone. Leukippos reveals his true identity, and challenges Apollo to reveal his. Instead, Apollo shoots Leukippos dead with his bow. Apollo begs Daphne’s forgiveness, saying he will grant her wish to join the natural world and will then love her in the form of a laurel tree. Her transformation begins, and her disembodied voice is heard among the rustling leaves.

About tonight: The evening got off to a rather stodgy start as a large phalanx of choristers slowly filled the stage space to sing An den Baum Daphne, an a cappella choral epilogue to the opera which Strauss composed in 1943. This seemed like a nice idea on paper, but the music overall is not terribly interesting, consisting of numerous repeats of a five-note theme familiar to me from DIE FRAU OHNE SCHATTEN. It seemed to go on and on, and while there were many appealing individual voices among the chorus, they did not always blend well. There were some pitch issues along the way, and a feeling that the piece was a bit under-rehearsed.

Then came an intermission, which completely killed the Straussian atmosphere that had been established, with people chatting blithely and wandering up and down the aisles. At last the opera itself commenced, but it took time for the crowd to re-settle.

DAPHNE is a gorgeous opera: a veritable feast of melody…there is never a dull moment musically. The vocal writing is extremely demanding; a very fine cast had been assembled, but their work was often undermined by over-loud playing from the orchestra. At the climaxes, voices were being forced in order to stay afloat, This has been happening at The Met a lot this season too, where conductors seem to think loud = exciting. Yes, there is a superficial thrill to it, but in the end it doesn’t do anyone any good.

That being the case, the singers could only be admired for holding steadfast and getting thru these taxing moments…especially when an orchestra is onstage behind you rather than in the pit.

The opera got off to an excellent start with baritone Kenneth Overton’s handsome singing as the 1st Shepherd. The voice is fresh and warm, and he cuts a fine figure to boot. Later in the opera, a trio of choristers come forward to portray his fellow shepherds: Jack Cottrell, Paul Holmes, and Blake Austin Brooks.

In the title-role, so ravishingly sung on the esteemed EMI recording by the great Mozartean Lucia Popp, Jana McIntyre displayed a clear, soaring lyrical sound that deftly encompassed the role’s wide range. It is a girlish timbre, perfect for expressing youthful vulnerability and impetuosity, but Ms. McIntyre also summoned considerable power when needed. In one especially lovely passage, her voice entwined with an obbligato from the ASO’s concertmaster, Cyrus Beroukhim. There were a few spots when the orchestra pressured the soprano, but she held her own and emerged unfazed. Daphne is a “big sing” and without a persuasive interpreter, the opera is not worth reviving. Ms. McIntyre not only sang beautifully, but she looked fetching in her pale lime-green frock, and she used her expressive hands with the grace of a ballerina to shape the music and send it out to us.

As two maids, Marlen Nahhas and Ashley Dixon were much more than supporting players: both have luscious voices, sounding very much at home in the Carnegie Hall space. In solo phrases, they were each truly appealing to hear, and then they duetted to charming effect. Their scene was not mere filler, but a musical treat all on its own.

Strauss hated tenors: that is what people say when listening to an otherwise fine tenor struggle with the demands of Bacchus or the Emperor in FRAU OHNE SCHATTEN, Tonight, both the leading tenors – rivals in the story – fared well, despite the assaults of the orchestra at certain inconvenient moments. Kyle Van Schoonhoven as Apollo (sometimes deemed Strauss’s cruelest tenor role) had the scope of the role, and the testing top notes were successfully attained. A more thoughtful conductor could have made the singer’s job easier but Mr. Van Schoonhoven was always impressive. And, in the more lyrical stretches, he displayed a very appealing timbre…and a sense of poetry.

As Daphne’s admiring swain, Leukippos, Aaron Blake made a striking impression. Slender of frame, and intense of presence, the tenor’s lyrical sound contains a vein of metal (aligned to crisp diction) that he can call upon to cut thru when needed. By turns playful and cocky, the character was portrayed to perfection, and the tenor unleashed a laser-beam sustained note as fate closed in on him.

Magnificent singing came from contralto Ronnita Miller (Gaea) and basso Stefan Egerstrom (Peneios), as Daphne’s parents. Ms. Miller, whose 1st Norn at The Met simply dazzled me a few seasons back, sings like a goddess with earthy chest tones of unusual richness. Stunning in her every note and word, the contralto looked like a fashion icon gowned all in black, and she shed her blessèd maternal light over the proceedings, even when sitting silently while others sang. Stefan Egerstrom, where have have you been al my life? What a powerful, resonant voice this man commands. He delivered his music with great authority: each note was rounded and true, and everything compellingly phrased. And yet, for all the strength of their voices, even Ms. Miller and Mr. Egerstrom were not immune to the effects of the encroaching orchestra.

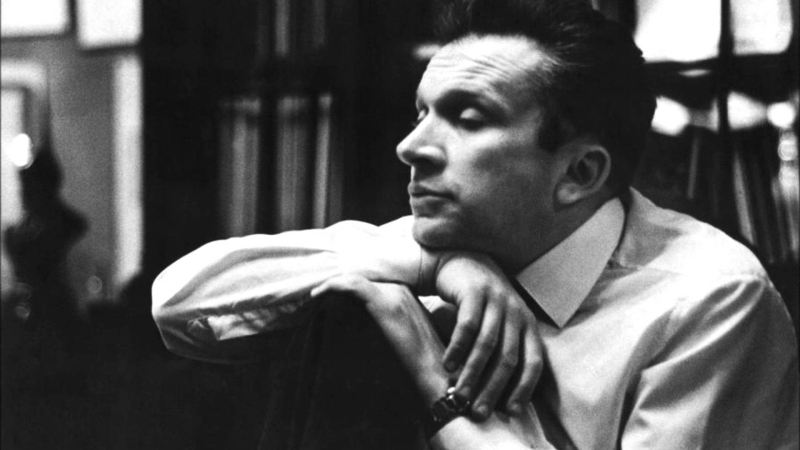

Above, onstage at Carnegie Hall (from left): Stefan Egerstrom, Ronnita Miller, Aaron Blake, Kyle Van Schoonhoven, Jana McIntyre, Leon Botstein (back to camera), and Ashley Dixon. Photo by Matthew Dine.

~ Oberon

![Duncan-Tyler-01[Colin-Mills] Duncan-Tyler-01[Colin-Mills]](https://oberonsglade.blog/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/dae97-6a00d8341c4e3853ef017c32d96229970b.jpg)