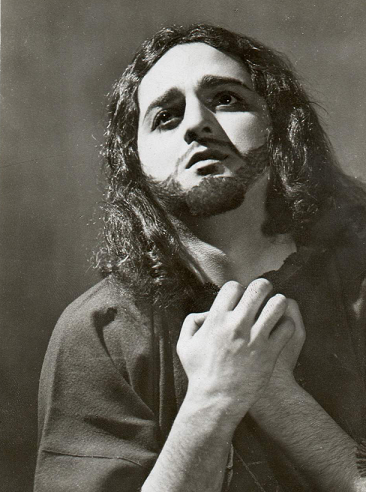

Above: Édouard Kriff as Samson

Searching for recordings by the Algerian tenor Édouard Kriff, I came upon this delicious work by Arthur Honegger: LES MILLE ET UNE NUITS (A Thousand and One Nights) written in 1937: LINK

I found these very informative paragraphs about Édouard Kriff by Philippe Olivier of The Orel Foundation:

“During Kriff’s first contract year at the National Opera House of Paris of September 1938, he sang the roles of Samson, Radames and Faust in LA DAMNATION DE FAUST by Berlioz. After the armistice of June 1940 , he appeared at the National Radio, mostly under the direction of Paul Bastide, in thirty leading roles. Denounced as a Jew by employees of the theater, he was arrested by collaborationist French police on 22 January 1943, along with his mother, but he escaped by jumping from the train to Sobibor; Kriff joined up with the snipers and partisans operating in the Ardèche.

In 1944, the tenor resumed his activities at the Opéra-Comique, where he sang Don José, Werther, Hoffmann and Canio in PAGLIACCI. He sang Julien in Charpentier’s LOUISE in 1950. From 1956 to 1958 he was stage director of the Opéra-Comique.”

It’s also wonderful to hear Germaine Cernay (above) in this exotic Honegger work. She’s long been a favorite of mine among voices from the past. Cernay she made her debut in 1925 at the Paris Opéra in Fauré’s Pénélope. She was a beloved star at the Opéra-Comique (Salle Favart), where she made her debut in 1927 in Alfano’s Risurrezione opposite Mary Garden and went on to appear there as Mallika (Lakmé), Suzuki, Mignon, Geneviève, Carmen, and Charlotte. She was also a favorite at La Monnaie, Brussels, and sang often at provincial French opera houses. She toured North Africa, England, Ireland, Italy, and Switzerland. Cernay is remembered as a fine interpreter of J.S. Bach.

Germaine Cernay was deeply religious, and in 1942 she retired from the stage and prepared to take her vows as a nun. She died – of an epileptic seizure – in 1943, before having fulfilled her wish to enter the convent.

Germaine Cernay sings Nevin’s The Rosary

The Honegger is conducted by Gustave Cloëz (above).