Above: pianist Wu Han

Sunday January 39th, 2022 – This evening’s program at Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center, entitled Romantic Perspectives, was truly a soul-warming experience, following a week of cold weather and a gusty snowstorm the previous day.

The program got off to an exciting start with a performance of the Scherzo from Johannes Brahms’s “F-A-E” Sonata for Violin and Piano, dating from 1853. With Wu Han at the piano, violinist Chad Hoopes brought real flair to his playing. From the buzzy opening, the two musicians were in perfect sync. This Scherzo has a lyrical interlude, wherein the players’ dynamics meshed ideally; then, back to a lively allegro. What an exhilarating way to start a concert!

Next came a spectacular performance of Gustav Mahler’s sole work in the chamber music genre: the Quartet in A-minor for Piano, Violin, Viola, and Cello, composed in 1876. Violinist Danbi Um, elegant in a ruffled ultramarine tulle gown, led her colleagues onstage. Before taking her place at the Steinway, Wu Han stepped forward to introduce us to two young musicians making their CMS debuts this evening: violist Timothy Ridout, and cellist Sihao He.

No pianist can establish a musical mood quite like like Wu Han does; with the deep, brooding opening measures of the Mahler, she immediately drew us in. The fabulous sound Sihao He summons from his cello was soon blending with Mr. Ridout’s handsome viola tone and the silken magic of Ms. Um’s violin. As the single movement progressed, the four musicians took us deeper and deeper into the music, their playing resplendently full-bodied and thrillingly intense. Passions ebb and flow, and then a darkish calm settles over us. Ms. Um’s exquisite playing, and the extraordinarily poetic phrasing of Mssrs. Ridout and He, were all underscored by Wu Han’s captivating dynamic mastery. It seemed impossible to think that only four players could produce such an ‘orchestral’ sound; their performance moved me deeply.

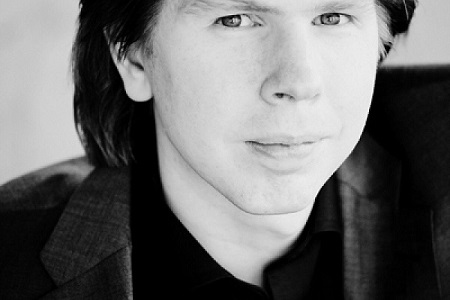

Above: violist Timothy Ridout

Composed in 1861, Antonín Dvořák‘s Quintet in A-minor for Two Violins, Two Violas, and Cello, Op.1, brought together the evening’s full string contingent: violinists Danbi Um and Chad Hoopes, violists Paul Neubauer and Timothy Ridout, and cellist Sihao He.

Written when Dvořák was twenty years old, this quintet was the first of his works to be ascribed an opus number. In the opening Adagio — Allegro ma non troppo, the unison slow introduction gives way to a dancing, animated feeling. The tone qualities of the five musicians were perfectly integrated, with Mr. Hoopes excelling in the numerous melodic flights for violin, nimbly seconded by Ms. Um; and Sihao He amplified the beautiful impression he had made in the Mahler. This movement has an unusual ending.

The ensuing Lento brings forth cantabile melodies; the main theme is taken up by Mr. Ridout’s viola (Dvořák’s own instrument) playing over a rhythmical accompaniment provided by the other players. The middle section of the movement provides a fresh theme, after which we hear a reprise of the introductory melody. The composer gives both violists ample opportunity here, and the contrasting timbres of Mssrs. Neubauer and Ridout were savourable indeed. The violins play in unison, then Mr. Hoopes again moved me with a high-lying passage. A swaying mood develops, and a rising violin motif leads us to the movement’s finish

The quartet’s Finale – Allegro con brio involves three primary themes. The marvelous sound of Sihao He’s cello was continually alluring to the ear, and Mr. Ridout again shone in a songful passage. The superb blend these five artists achieved carried us on to the work’s ending, hailed by the crowd with warm applause.

It is interesting to note that Dvořák seemingly never heard his opus 1; its first public performance came seventeen years after his death, and it was not published until 1943.

Above: cellist Sihao He

Having recently enjoyed Maxim Vengerov’s stunning performance of César Franck‘s Violin Concerto at Carnegie Hall, I was definitely in the mood for more of Franck’s music. This evening’s CMS program ended with the composer’s Quintet in F-minor for Piano, Two Violins, Viola, and Cello, dating from 1879.

With a descending phrase from Danbi Um, the passionate slow introduction to the first movement is underway. Wu Han’s gorgeous entry has a hesitant feeling, as if the composer is not quite sure where he wants to take us; a rather fitful acceleration finally achieves Allegro status. Now all five players begin to pass the melodies from one to another. Mr. Neubauer’s dusky viola, Wu Han’s magical piano, the lovely sense of longing from Danbi Um’s violin, the poignant sound of Sihao He’s cello…all combined as the music turns huge. In this movement, a melody of chromatic half-steps is heard, creating a musical tension which our players today clearly relished.

The second movement, marked Lento, con molto sentimento, begins with a haunting theme from Wu Han’s keyboard, and sublime lyricism from Danbi Um. The chromaticism which awoke in the opening movement becomes more pervasive now, with Ms. Um and Mr. He trading phrases. Wu Han’s playing is heavenly, and the cellist is simply stunning. The music builds in grandeur and then dissipates, becoming celestial. Mr. Neubauer’s lovely viola passage, ethereal sounds from the piano, and Danbi Um’s haunting violin draw the movement to a tender finish.

Chad Hoopes opens the final movement with a bustling motif, joined by Ms. Um in an agitato mode. The strings play the work’s main melody in unison, with a vibrant crescendo. A brief, sweet song from Danbi Um leads to a big build-up of sound and emotion as the quintet sails onward to an epic finale.

A full-house standing ovation greeted the players, who were called back for a second bow, much to everyone’s delight.

~ Oberon