~ Author: Scoresby

Thursday May 17th, 2018 – It is truly a rare occasion to see Carnegie Hall‘s Stern Auditorium completely sold out. It is even rarer to see this happen with stage seating too as was the case with pianist Yuja Wang‘s recital last week. Only Ms. Wang could do so with an unrelenting program like the one she played, with dark, not necessarily crowd pleasing works by Rachmaninoff, Scriabin, Ligeti, and Prokofiev. I haven’t enjoyed Ms. Wang’s solo performances as much in the past, but this felt like a completely different atmosphere than her usual fair. For one, the repertoire was much more intellectual and music lover oriented than her usual programs. For another, this program really seemed to be a statement. If it was any indication of how Ms. Wang’s Perspectives series will be at Carnegie Hall next season, I look forward to being able to attend the many events.

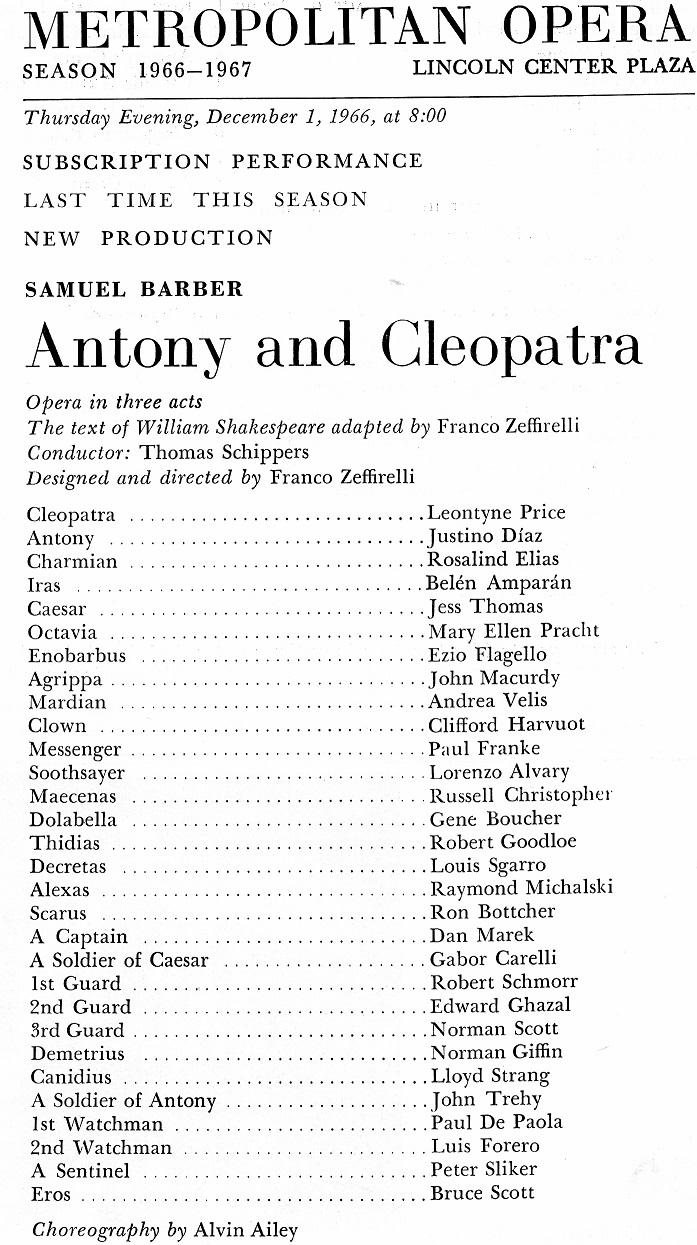

Above: Pianist Yuja Wang; Photo Credit: Kirk Edwards

Ms. Wang began the performance with a series of seven Rachmaninoff’s smaller works, all in minor keys and repeated keys back to back (except for the opening g minor prelude). Despite clapping from the audience in-between the works, it was obvious Ms. Wang wanted to play them as one giant set. These set up the rest of the concert incredibly well – she drew in the crowd with a sense of mystery, making Rachmaninoff’s writing sound much more modern than it typically is treated. Emphasizing dissonances and unstable textures, Ms. Wang’s Étude-tableau in C minor, Op. 39 No. 1 sounded like a torrent in the right hand with crisply articulated left hand percussion. But here the blurs and ripples took control – while the notes were clear, Ms. Wang managed to make the voicing fade behind the accompaniment making the piece more modernist.

In the Prelude in B Minor, Op. 32 No. 10, Ms. Wang’s sensitive dynamic range and languid playing made the romantic climax seem less important than the surrounding, Debussy-like material. The best part of the evening was the Étude-tableau in E-flat Minor, Op. 39 No. 5 which ended the set. Here Ms. Wang had an unparalleled light touch which managed to let the melody sing through the storm of darker undercurrent. This was the opposite of virtuoso playing – many pianists hammer this etude out without much subtlety. Instead, Ms. Wang let the music’s storminess speak for itself, which led perfectly into the Scriabin that came next.

The next work on the program was Scriabin Sonata No. 10, Op. 70. This is one of Scriabin last five pieces written for piano and has his characteristic mystical sound world in the extreme. While work is in much stricter sonata form than the other late piano sonatas, it still has a mysterious, almost ghostly atmosphere. Ms. Wang wove through the dense textures with ease, making both the structure clear and letting the ambiguous atmosphere seem full of color. Her notes never sounded crisp or grounded; they instead were washed with an ethereal sheen. Just as the magical trills that appear before the work launches into its second theme began to be played, someone’s cellphone ringer featuring a trilling bird went off.

From the Archive: Alexander Scriabin

While admirably Ms. Wang continued to play, it was a funny indication of the music. The trills begin to take over the more melodic portions of the piece before the climactic recapitulation where tremolos and trills rule in all registers – as Scriabin put it “a blinding light”. Ms. Wang’s glossy playing made this piece seem remote in the best way possible – someone taking you into their isolated world. Adding to this effect was the stage seating. In order to accommodate everyone on the stage without disrupting the performance, Carnegie lowered the lights so there was just a small circle of light around Ms. Wang – making her seem in that same realm as Scriabin.

To finish the first half of the program, Ms. Wang performed three short, but difficult Ligeti Etudes: No. 3 Touches bloquées, No. 9 Vertige, and No. 1 Désordre. To be clear, the Ligeti Etudes are some of the hardest pieces for piano ever written, but each one is also a musical world into itself. After the otherworldly Scriabin piece, Touches bloquées offered a different kind of isolation: that of machinery. The work sounds like a giant machine jerking around – Ligeti gets this odd rhythmic effect by having the pianist strike some keys silently in order to build in a particular rhythm to the piece.

Ms. Wang gave a committed performance that captured all of this convulsive sound. Vertige is modeled after a falling Shepard’s Tone with many chromatic notes lined up and falling forever. Ms. Wang player her way through this exhausting etude with verve – plucking out each of punchy chords in-between the falling. Finally, the first half ended with the jazzy and punchy disorder, a funny musical joke by Ms. Wang after such a dark/intellectual first half.

From the Archives: Composer Györg Ligeti

After what seemed more like a 30 or so minute intermission, the final work on the program was Piano Sonata No. 8 in B-flat Major, Op. 84. Despite the program notes saying that this was Prokofiev’s most optimistic of the war-time sonatas – the sprawling first movement of this piece a moody, wandering work. Ms. Wang’s performance captured the eccentric melody lines and temperamental well. She used a similar remote style of playing that she used in the Rachmaninoff and Scriabin here, but with well timed percussive outbursts in the bass that gave a contrasting mood.

In the Allegro moderato sections of the first movement Ms. Wang’s rapid fire style of playing was thrilling to watch, bringing the movement to a climax. More impressive though was Ms. Wang’s sense of space and silence at the end of the movement. In the romantic second movement, Ms. Wang seemed at her warmest of the night in the lighthearted theme before plunging into the electric final movement. Here, Ms. Wang plucked out precise articulation with a lithe sound, speeding through the virtuosic sections. The highlight was the mysterious coda-esque moment before the last outburst. Here Ms. Wang seemed relish in the atmosphere before the crashing ending (which had all the tight control of the rest of the performance).

While a thrilling recital from start to finish, I do wonder if her diverse crowd found it as satisfying. In many ways this was her at her most introspective – no crowd pleasing works like her usual programs and while certainly virtuosic playing, emphasizing the ephemeral instead of flash. Ms. Wang has a history of extensive encores, as such the crowd didn’t seem surprised when she brought out five of her favorite show-stopper type pieces. The crowd seemed enthused with these – much more so than the pieces on the actual program. While Ms. Wang wasn’t indifferent to her crowd, she certainly seemed all-business this evening with brusque bows and a sense of pushing forward. As a final gesture she played Liszt’s transcription of Schubert’s Gretchen am Spinnrade, going back to that dark place of the rest of the concert and seemingly shunning the audience there to hear her – it was like magic.

~ Scoresby