(This article about the great singing-actress first appeared on Oberon’s Grove in 2008; it included many more photos, but for this revival, I’ve chosen a few special favorites.)

Back in 1968, I was at a performance of CAV/PAG at NYCO and the soprano singing Nedda caught my fancy, not just because she was slender and sexy and moved with a natural command of the stage, but also that at one point she stamped out a cigarette with her bare foot. I could not think of many divas who would do that.

I could write a book about Maralin Niska; her performances are among the most potent memories I have of that heady time in the 1960s-1980s when so many great singers played nightly at both of New York’s opera houses.

Her voice was unconventional; an enigma, really. I would not call it beautiful though she could convince you that it was utterly gorgeous in certain phrases. Her technique was based very much on a chest resonance which gave her unusual power; while the timbre of her voice was dark, the thrust of it was very bright. When I think of other great singing-actresses I have seen – Rysanek, Silja, Behrens – Niska stands firmly in their company and she was the most versatile of them all. She was a striking woman; I remember her being referred to as the Rita Hayworth of opera.

In 1969, while the Met was closed due to a strike, Maralin was alternating Mozart’s Countess Almaviva with the role of Yaroslavna at NYCO. Two more dissimilar roles would be hard to imagine but she was utterly at home in both. Her Countess had an almost tragic dimension as she suffered the indignations her husband heaped on her; she used her perfectly supported piano technique to great effect in Mozart’s music. As Yaroslava, left by Prince Igor to run the unruly kingdom while he is off fighting Khan Kontchak, Niska sang a hauntingly hushed lament for his absence. But when the rebels set fire to the palace, Maralin, surrounded by the thundering chorus of boyars, let fly with an unscripted high-D which was as thrilling as any note I’ve ever heard in an opera house.

As Marguerite in FAUST, Niska was anything but a shrinking violet. Faust was the key to her sexual awakening and when he bade her adieu in the Garden Scene, Niska broke into sobs of frustrated passion. Her overwhelming power in the final trio, and her devastating rejection of Faust at the end literally ring in my ears even today.

The vocal and dramatic strokes Niska used in her canvas remain vividly alive for me all these years later. In BUTTERFLY, kneeling with Suzuki and Trouble with backs to the audience as the Humming Chorus is intoned and evening falls, Niska slowly looked over her shoulder to the audience with an expression of quiet fear: Butterfly’s unshakable faith would not pass the test. In TRAVIATA, having been asked by Germont pere to give up his son, Niska sustained the opening of “O, dite alla giovine” with a remarkable hushed tone and drew no breath before continuing. With that phrase, Violetta’s fragile world comes undone. No other soprano has done it quite the same way. But I went backstage afterwards and said, “Maralin! That NOTE!” “Which note?” “The note before “Dite alla giovine!” “Um…yes?” “You held it so long and so quietly and then went into the phrase without breathing!” “I did?”

She sang Tosca, her contempt for Scarpia expressed with icy power. After she had murdered him, she knelt by his corpse and sang “E morto…or gli perdono!’ and with a swift stroke buried the blade of the knife into the stage about an inch from the baritone’s head. Then she sang Mimi, and I thought she’d be way too cold for that. But she told an interviewer: “I put on the costume and I became Mimi.” Using portamenti and her miraculous piano, Niska did indeed become the pathetic seamstress.

Niska was also singing at the Met by now, in VESPRI and TOSCA among other operas. She was wonderful and wove her own magic into the existing stagings.

Above: Maralin as Medea

NYCO mounted Cherubini’s MEDEA for her. This complex role, sometimes sung as a verismo shrew, was more classically structured by Niska who seemed to realize that vocally Medea is more akin to Donna Anna than anything else. Moreover, she convinced me that Medea was “right” and that her horrific murders of Glauce and of her children were perfectly natural. I never saw Callas in opera, but it would be hard to imagine she was any more potent a Medea than Niska.

At NYCO she continued in her Mimi mode with a beautifully expressive Manon Lescaut. Then she took on Salome, having just the ideal combination of silver & blood in the voice. I was dazed by the mesmerizing, obsessive power of both her singing and her portrayal. The art deco sets were superb, and Niska ended her dance in a shimmering body stocking. In the end, as the soldiers crushed her, Maralin let out a chesty groan and writhed for a moment before death took her.

Then came one of her most delightful and unexpected triumphs: the Composer in ARIADNE AUF NAXOS. This is my favorite opera and I just loved NYCO’s production which seemed to capture the two colliding worlds to perfection. Maralin sang the idealistic Composer, who is finally forced to deal with the realities of life in the theatre, with a flood of dark, soaring tone and vivid dynamic control. The Composer disappears at the end of the Prologue, but in this production, Niska entered the pit and “conducted” the opening of the opera; then Julius Rudel, already seated next to the podium, took over after several measures.

TJ and I had moved to Hartford and were stunned one night when we went to see TRAVIATA at the Bushnell to find that Maria Chiara had cancelled and Maralin was replacing her. “Let’s go leave her a note!” suggested TJ. Rushing to the stage door, we came upon Maralin pounding on the “wrong” door, trying to get into the theatre where she’d never performed before. She was thrilled to see us, not least because we were able to show her the right door.

FANCIULLA DEL WEST was another perfect Niska creation; she seemed just to “become” this unpretentious, good-hearted Wild West woman…not above cheating at cards to win her man.

TURANDOT was a role we never got to see her do; apparently NYCO asked Maralin to learn it for the LA tour, promising her performances in NYC afterwards. The promise was broken. But I have a tape of the LA performance and it’s pretty impressive.

Maralin sang the unlikely role of Rosalinda in FLEDERMAUS and, at Carnegie Hall, the Latvian national opera BANUTA in which her steely top notes and powerful chest voice were thrillingly on display.

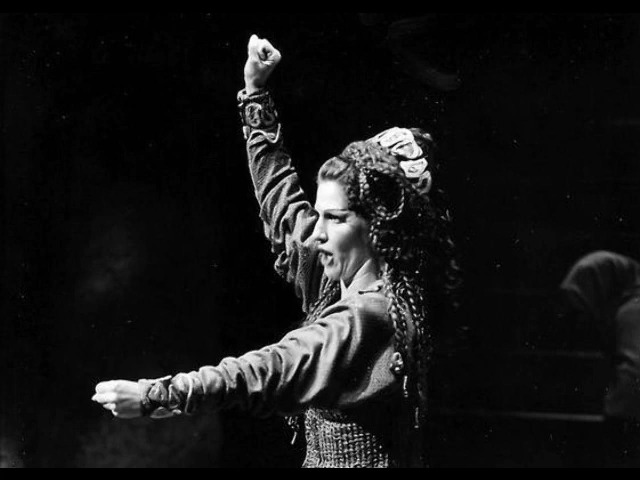

Above: Maralin as Emilia Marty

Niska’s greatest triumph, though, was in the Frank Corsaro production of Janacek’s MAKROPOULOS AFFAIR. This fascinating story of a 342-year-old woman who has spanned the decades under various names (always using the initials E.M.) thanks to her alchemist father’s potion for eternal life has been fashioned by Janacek into a vivid drama which centers on Elina’s need to find the lost prescription: she needs a dose to extend her life another 300 years. Ruthlessly manipulative, she manages by seduction to attain the formula only to decide in the end that she is weary of life. Corsaro told the story of the opera onstage while overhead, films of episodes from EM’s past are shown on multiple screens. Maralin appears in the films in various period costumes, using and abusing her sexual fascination to get what she wants from her various lovers. Onstage there is a nude scene where EM removes her dressing gown to show Baron Prus the scars inflicted by one of her sadistic lovers; few divas besides Niska have the body to appear nude onstage. It seemed entirely natural. In the end, Elina offers the magic formula to the young Christa who burns it; spontaneously all the screens burst into flame and out of the darkness, EM’s enigmatic chauffeur comes to bear her away into the smoke. The ovations Maralin received for these performances rivalled any I have encountered in the theatre.

I saw her onstage for the last time as Elisabetta in MARIA STUARDA; she was still singing with amazing force but NYCO had decided they didn’t need her – even though the latest revival of the Janacek had been even more powerful than the original run. But she threw herself into the Donizetti, brazenly sailing in and out of registers and treating Maria (Ashley Putnam) with palpable disdain. After signing Maria’s death warrant, Elizabetta turns on the hapless Leicester and orders him to be witness to Maria’s execution. Launching her final stretta with almost gleeful vengeance, Niska propelled the scene to its climax and struck a brazen high E-flat which rang into the house (and onto my tape recorder!)

She moved to Santa Fe and we kept in touch. Then one year my Christmas card came back marked “No such number”. I wrote again: same thing. I feared we had lost contact.

I thought about her all the time; and the power of thought worked. Shortly after I moved to NYC, I was working one morning and down the aisle Maralin came walking. She was in town with her husband Bill Mullen for a NYCO “family reunion”. We had the most amazing conversation and established why my letters hadn’t reached her. Three years later she was in town again and came in expressly to say hello.

Now I’m re-reading what I’ve written. How feeble it sounds; I don’t think l’ve begun to express the impact of her performances. My diaries have much more detail, but even they seem very pallid. It’s the impressions she made on my mind or my…soul…that can’t be defined. The diaries, the old tapes, the photos, the programmes, notes she sent me. No one could grasp from any of this what Maralin Niska really meant to me. But I wanted to try to express it anyway.

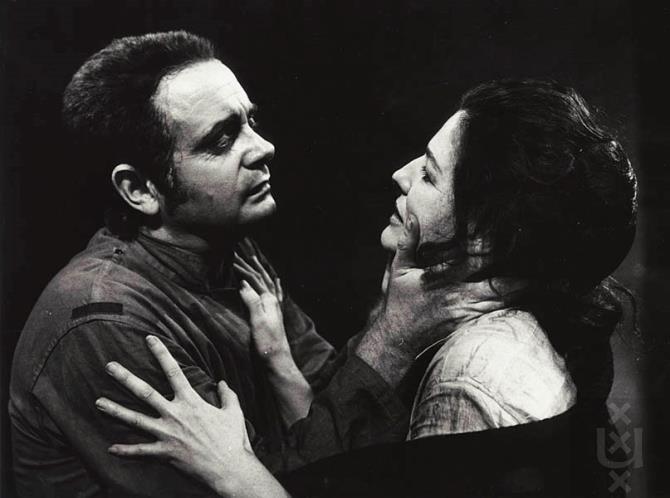

Above: with baritone Jan Derksen in WOZZECK, one of Maralin’s European triumphs