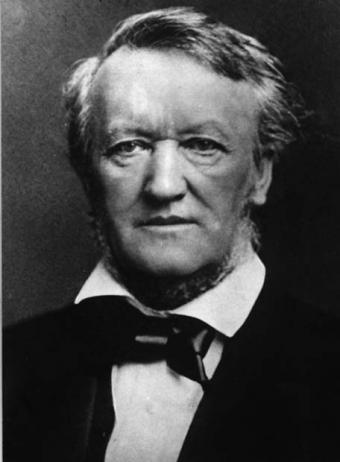

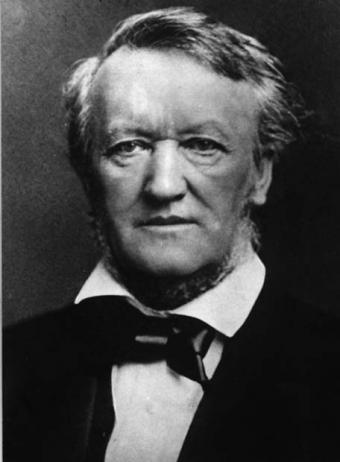

Above: Richard Wagner

Having taken a break from listening to Wagner at home while I was wrapped up with attending the RING operas at The Met, I picked up where I’d left off in playing CDs that my friend Dmitry has graciously made for me. These live recordings all come from a valuable source, Opera Depot, and this latest round of Wagnerian adventures kicks off with a 1966 performance of FLIEGENDE HOLLANDER from Covent Garden.

HOLLANDER was not the first Wagner opera I ever experienced in the theatre, but my first encounter with it (in 1968) was a memorable event with Leonie Rysanek (singing despite a high fever) magnificent as Senta, and Walter Cassel, James King and Giorgio Tozzi as the male principals.

Above: Dame Gwyneth Jones

For this 1966 performance from London, Sir Georg Solti is on the podium, stirring up a vivid performance that comes across excitingly in this recording which is in pretty good broadcast sound, with the voices prominent.

David Ward is a bass-oriented Dutchman and his singing is moving in its passion and despair, fierce in anger and with a touching human quality in the more reflective passages. He and his Senta, Dame Gwyneth Jones, manage the strenuous demands of their long duet very well: both the tessitura and the emotional weight of this duet test the greatest of singers and if there are slight signs of effort here and there in this recording, the overall effect is powerful.

Dame Gwyneth, just two years after her break-through performance at The Garden in TROVATORE casts out the powerful top notes before her final sacrificial leap thrillingly; earlier, in the Ballad she is engrossing in her use of piano singing and creates a haunting picture of the obsessed girl. The soprano’s well-known tendency to approach notes with a rather woozy attack before stabilizing the tone is sometimes in evidence; I find it endearing.

The great basso Gottlob Frick is a wonderful Daland, and tenor Vilem Pribyl holds up well in the demanding role of Erik; his third act aria – which recalls Bellini in its melodic flow – is passionately sung. Elizabeth Bainbridge and Kenneth MacDonald give sturdy performances as Mary and the Steersman.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

A WALKURE Act I from Bayreuth 1971 finds conductor Horst Stein (above) giving a great sense of urgency to the opening ‘chase’ music. Helge Brilioth, probably better known for his Tristan and Siegfried, sounds a bit rough-hewn at first as Siegmund but summons up some poetry later in the act. Dame Gwyneth Jones as Sieglinde shows both contemplative lyricism and the power of a future Brunnhilde; her singing is emotional without breaking the musical frame. Karl Ridderbusch is a darkly voluminous Hunding; despite a few moments of sharpness here and there, he makes a strong impression.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~“

The Swedish singer Berit Lindholm (above) was one of a group of sopranos – Rita Hunter, Ingrid Bjoner, Caterina Ligendza and Dame Gwyneth Jones were some of the others – who increasingly tackled the great Wagnerian roles as Birgit Nilsson’s career wound down. In 1976 Lindholm sang Brunnhilde in a performance of GOTTERDAMMERUNG at Covent Garden conducted by Sir Colin Davis, and she does quite well by the role, bringing a more feminine and vulnerable quality to her interpretation than Nilsson did. Lindholm reaches a fine peak as Act I moves toward its inexorable climax with the meeting between Brunnhilde and Waltraute, followed by the false Gunther’s rape of the ring.

Interestingly, though both the recording and the Covent Garden website list Yvonne Minton as Waltraute in this performance, there is some question that she might have been replaced last-minute by Gillian Knight; in fact, some listings for this recording on other releases do show Knight singing Waltraute. A delicious mystery, since whichever mezzo it is is impressive indeed. (I’ve left an inquiry on the Opera Depot listing, perhaps someone can shed further light…)

Jean Cox certainly has an authentic Wagnerian voice though at times in Act I his singing falls a shade below pitch. The wonderful basso Bengt Rundgren sounds fine as Hagen in Act I, and his half-siblings are Siegmund Nimsgern – later a Bayreuth Wotan – as Gunther, and Hanna Lisowska as Gutrune, a role she repeated at the Met when the ‘Levine’ Cycle was filmed for posterity.

As an admirer of the Norn scene, I’m very pleased with the three women who sing this fantastic music here: Patricia Payne, Elizabeth Connell and Pauline Tinsley. Ms. Payne is steady and sure of voice and what a delight to hear a future Isolde (Ms. Connell) and Kundry (Ms. Tinsley) in these roles; Ms. Tinsley dips impressively into her chest voice at one point, an unusual and exciting effect.

Sir Colin Davis builds the great span of the prologue/Act I persuasively; a few minor orchestral blips here and there are barely worth mentioning. Once Waltraute arrives at Brunnhilde’s Rock the conductor attains a heightened level of dramatic intensity and the act ends excitingly.

Act II opens with the mysterious conversation between Alberich and his slumbering son, Hagen. Zoltán Kelemen, who was Karajan’s Alberich when the conductor inaugurated his RING Cycle at The Met (a project from which the maestro withdrew after the first two operas) makes a fine effect, and Mr. Rundgren maintains his sturdily sung Hagen throughout this act. Jean Cox is very authoritative as he declaims his oath on Hagen’s spear; any misgivings about him from Act I are swept away here. Berit Lindholm may lack the trumpeting, fearlessly sustained high notes of the more famous Nilsson, but her Brunnhilde is exciting in its own right, with her anguished cries of ‘Verrat! Verrat!’ (“Betrayed!”) a particularly strong moment.

Whether she is the Waltraute or not, Gillian Knight is definitely one of the Rhinemaidens, joined in melodious harmonies by Valerie Masterson and Eiddwen Harrhy for the opening scene of Act III. There’s some vividly silly giggling from this trio, and Ms. Masterson in particular sounds lovely – an augury of her eventual status as a fabulous Cleopatra.

Mr. Cox has impressive reserves to carry him thru Siegfried’s taxing narrative – he’s at his best here – and if Ms. Lindholm’s voice doesn’t totally dominate the Immolation Scene, she’s very persuasive in the more reflective passages of Brunnhilde’s great concluding aria. Sir Colin Davis had built the opera steadily and with a sure sense of the music’s architecture; he saves a brilliant stroke for the end of the opera when he does not take the ‘traditional’ pause before the reprise of the ‘redemption thru love’ theme but instead sails forth into it with impetuous fervor.

There were times while listening to this performance when I wondered if this was a broadcast performance or was recorded in-house. The voices do not always have the prominence we associate with broadcast sound, but perhaps the micorphones were oddly placed. At any rate, GOTTERDAMMERUNG has again made its mark as the culmination of the great drama of The RING.