Above: Lisa Batiashvili, photo by Sammy Hart/DG

~ Author: Oberon

Friday November 22nd, 2024 – Tonight at Carnegie Hall, the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra opened their program with the US premiere of Body Cosmic by the orchestra’s composer-in-residence, Ellen Reid. One of my all-time favorite musicians, Lisa Batiashvili, then offered Prokofiev’s Violin Concerto No. 2. Following the interval, the Concertgebouw’s Chief Conductor Designate Klaus Mäkelä led a seemingly endless performance of Rachmaninoff’s 2nd Symphony.

Annoyances put us in a bad mood as we waited for the concert to begin: the Hall was freezing cold, and the start time ran late. Then came the silly tradition of the musicians making an entrance, obliging the audience to applaud as they leisurely took their places. Most people don’t get applause just for showing up at their job. After the music started, a squirmy (but silent) little girl next to us had a squeaky seat that made a metallic grinding noise every time she moved, whilst the young man behind us kept kicking the backs of our seats (he must have been man-spreading to cover so much territory). At last the house lights dimmed, and the conductor took the podium.

The US premiere of Ms. Reid’s Body Cosmic was indeed what – back in the days of smoke and wine – we’d have called kozmic. The piece has a magical start, with rising passages lifting us out of the ordinary world into an airy, buzzy higher place. Is that a vibraphone I hear?

A key player in the work is the Concertgebouw’s harpist, though I cannot tell you which of the orchestra’s two principals was playing since my view of her was blocked by her harp. Meshing with the flutes, the harp evokes a drifting feeling. The concertmaster – or ‘leader’ as he is listed in the Playbill – Vesko Eshkenazi, has much to do in this 15 minute piece, and his sound has a luminosity that delights the ear. Likewise, the trumpet soloist is really impressive, though again their are two possibilities listed in the roster.

The music becomes increasingly rich in texture; it’s beautiful in an other-worldly sense. Muted trombones sigh, and then things get a bit jumbled. The violins, on a sustained high tone, clear the air. The harp again makes heavenly sounds, as distant chimes are heard. Flutes and high violins have a counter-poise in the deep basses (the Concertgebouw’s basses are particularly impressive). The music comes to a full stop.

A violin phrase sets the second movement on its way; did someone whistle? The flutes trill and shimmer, with the concertmaster playing agitato; the basses and celli plumb the depths. The music turns fluttery, and then brass fanfares sound. A continuous beat signals a sonic build-up; with large-scale brass passages, things turn epic, only to fade as the harp sounds and the flutes resume their trilling. The world seems to sway, the trumpeter trills. A march-like beat springs up and then speeds up, evoking a sense of urgency. Following a sudden stop, a massive chord sounds: thunderous drums seem to announce a massive finish, but Body Cosmic ends with a solitary note from the violin.

I can’t begin to tell you how absorbing and ear-pleasing this music was: so much going on, and all of it perfectly crafted and fantastically played. The composer, who was awarded the 2019 Pulitzer Prize in Music for her opera, p r i s m, looked positively dishy in her unique blue and white frock – which featured a leggy mini-skirt and a charming train – when she was called onto the stage for a bow. She was greeted by both the audience and the players themselves with fervent applause. Ben Weaver, who is with me – and who is often resistant to “new music” – admitted that he’d enjoyed it.

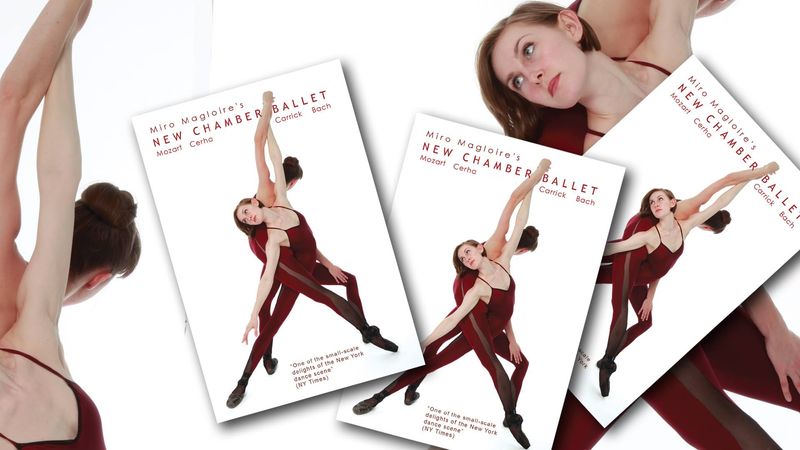

Ms. Batiashvili then took the stage, having stepped out of the pages of Vogue in her stunning black gown: the very picture of elegance. Back in the days when Alan Gilbert was in charge of the NY Phil, Lisa appeared there often; she and the Maestro had a very special rapport, and I recalled how much I always loved to watch their interaction…almost like partners in a dance. Ms. Batiashvili sounds as gorgeous as she looks; her timbre has a particular fragrance, something no other violinist of my experience can quite capture.

The Prokofiev concerto opens with the soloist playing alone: a hushed lament. The ensemble joins, taking up the theme. As the music becomes more animated, the violin sails thru fast figurations over the beating accompaniment of the basses. The music slows, and a fresh mood is then established, rather jaunty, with the soloist busily employed with reams of notes or with lyrical motifs, whilst unison basses and celli add a darker colour. Fanfares sound, and with Ms. Batiashvili playing at high-speed, everything breezes along…and then the music stalls. The low strings get things back on track, carrying the movement to a quirky finish.

The Andante assai is a gracious slow dance; it has a dotty start as the familiar theme sounds over plucking strings. Ms. Batiashvili was mesmerizing here, her control and phrasing so enticing: both her presence and her playing tell of her innate grace and loveliness. This theme then repeats itself, now with the feel of a swaying rubato, and here Lisa is just plain magical. A sort of da capo finds the orchestra taking up the theme and the violin playing rhythm.

In Prokofiev’s final Allegro ben marcato, Ms. Batiashvili dazzled us with with her virtuosity. Introducing fresh colours to the music, the composer adds castanets, the triangle, and the snare drum to his sonic delights. In a fascinating passage, Lisa’s slithering scales are underscored by the bass drum and double bass before we are swept along into the finale.

Having put us under her spell for a half-hour, Ms. Batiashvili responded to our heartfelt applause with a Bach encore (I’ll have the details of the piece soon, hopefully…and some photos, too!) and then she was called back for a final bow, the musicians joining the audience in homage to this sublime artist.

Update: Lisa’s encore was J. S. Bach’s Chorale Prelude on “Ich ruf’ zu dir, Herr Jesu Christ” (arranged for Violin and Strings by Anders Hillborg).

Following a drawn-out interval, the Rachmaninoff 2nd made its deep start with the strings and horns sounding darkly gorgeous. I was taking notes, thoroughly engaged in the music. But after a while, things began to wear thin. The playing was simply grand – the solo voices among the orchestra all marvelous – and so is the music…so why am I losing my focus? By the time the big, ultra-familiar cinematic theme of the Adagio commenced, I was getting restless. It all seemed like too much of a good thing. The final movement was a succession of ‘finales’ which turn out to be culs de sac, forcing the players back to the main road, seeking an exit.

After nearly an hour, the symphony ended to an enormous ovation and everyone in the Hall immediately leapt to their feet. My sidekick Ben Weaver and I hastened out into the rain. Ben was actually angry about the way the Rachmaninoff was done; he blamed the conductor. Then he told me that the composer had realized the work was too long and had later sanctioned cuts; tonight we’d heard the original, which is what made the music – which has a richness of themes and of orchestration that would normally thrill me (and it did, for the first quarter-hour) – feel like overkill to me. Often a composer’s second thoughts are more congenial to the ear than his original concept.

~ Oberon