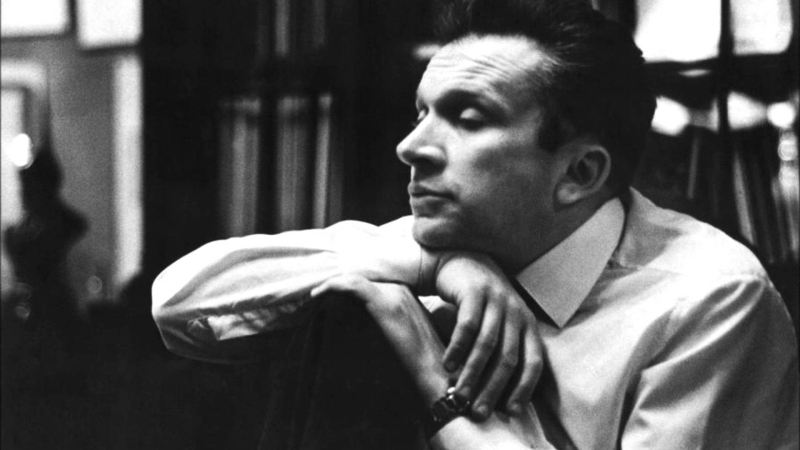

Above: tenor Dominic Armstrong (seated), conductor Leon Botstein, and soprano Felicia Moore onstage at Carnegie Hall; photo by Matt Dine

~ Author: Ben Weaver

Friday March 22nd, 2024 – Arnold Schoenberg’s gargantuan Gurre-Lieder, composed in 1900-03 (revised 1910-11), is unlike anything else in his catalog. With this lush and highly melodic work – for soloists, chorus and orchestra – he reached the ceiling of Romanticism and the only way out was to shatter it to smithereens. For Schoenberg, a mix of musical philosophy and observing the ravages of WWI signaled that music could not continue on the path laid out by his predecessors (Bach, Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Brahms, Wagner, etc. etc.) Schoenberg may have overreacted quite a bit, but, at a least with Gurre-Lieder, he left us with a grand finale of sorts to the excesses of 19th century music.

Gurre-Lieder’s libretto is adapted from Jens Peter Jacobsen’s dramatic poem Gurresange, written in 1868. It tells the story of King Waldemar and his love for the beautiful Tove, who is murdered by Waldemar’s jealous wife. Enraged, Waldemar curses God and is condemned to roam every night on wild hunts with his ghostly vassals. Waldemar is redeemed with arrival of Spring, and he and Tove are reunited as they become one with nature. Performances of this work are extremely rare, no doubt because Schoenberg calls for more than 150 musicians, an extravagance few organizations can afford, and none can afford frequently.

Part I opens with what Gabriel Adorno called “fairy land” music, a shimmering tapestry of harps, celesta, flutes, piccolo and some strings. Waldemar and Tove exchange declarations of love in extended monologues, set to ravishing Wagnerian and Straussian sounds.

Tenor Dominic Armstrong (above) took on the – let’s face it – impossible role of Waldemar. Schoenberg wrote the part for at least three different voices; not many singers have been able to possess them all. This is a Tristan/Parsifal/Tannhäuser part, with Tamino thrown in for good measure. I honestly don’t know who can really sing all this in a live performance. Dominic Armstrong is a lyrical tenor with a strong top, but sadly the voice disappears in the lower registers. And conductor Leon Botstein was not very kind, allowing the orchestra to cover Mr. Armstrong all evening. Armstrong’s strongest moments were in the lighter passages; his best singing came late in Part 3, in his final aria “Mit Toves Stimme flüstert der Wald”, when Schoenberg’s orchestration relaxed, allowing Waldemar to finally emerge.

Soprano Felicia Moore (above) possesses a large, blooming voice, that managed to break through the orchestral cacophony, in spite of an insensitive conductor. Her Tove was exotic and warm.

Mezzo-soprano Krysty Swann (above, in a Matt Dine photo), as the Wood-Dove who describes the terrifying details of Tove’s murder, was exciting in her long monologue. The voice is large and steely, the vibrato a bit loose at the top, but Ms. Swann possessed an excellent sense of drama, managing to build to thrilling and hair-raising final moments of the Wood-Dove’s narrative.

Bass-baritone Alan Held (above, photo by Matt Dine) has been a favorite of mine for many years. Though it seemed like James Levine always kept Mr. Held back at the Metropolitan Opera, where he should have been singing Wotan among many other roles, I still vividly recall a searing Wozzeck Mr. Held sang at the Met in 2011. It was wonderful to hear him once again, his large voice easily filling Carnegie Hall as the Peasant who is terrified by Waldemar and his men’s nightly processions.

Tenor Brenton Ryan (photo above by Matt Dine) was a very memorable Klaus the Jester, starting his long monologue from the house floor, then jumping on to the stage. Mr. Ryan possesses a strong, characterful tenor that made me think he might have been a better choice to sing Waldemar.

And German bass-baritone Carsten Wittmoser was a magnificent Narrator, his crystal clear diction perfect for the sprechstimme part, which is usually given to older singers nearing retirement or even non-singer actors (Karl Maria Brandauer and Barbara Sukowa, for example.) So it was nice to hear a singer still in his prime take on this role.

The American Symphony Orchestra was founded by Leopold Stokowski – who conducted the US Premiere of Gurre-Lieder in 1932, so it has a direct connection to this work, and they played quite beautifully, and certainly loudly. Here I must fault Leon Botstein for not being more considerate of his singers. Even the Bard Festival Chorale found itself drowned out by the orchestra, occasionally becoming just a mass of garbled sounds coming from somewhere at the back of the stage.

Still, any live performance – flaws aside – of this supremely difficult work is was a special treat to be able to experience. How long before another performance is organized in New York City?

~ Ben Weaver

Performance photos by Matt Dine, courtesy of Carnegie Hall