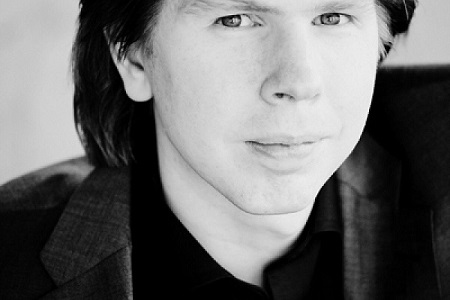

Above: pianist Anne Marie McDermott

~ Author: Oberon

Sunday November 24th, 2019 – A thoughtfully-devised program this evening at Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center gave prominence to the inspired – and inspiring – pianist Anne-Marie McDermott. Ms. McDermott has given me some of my happiest times at CMS, most memorably with her playing of Mozart’s K. 466 in May 2018: a performance which drew a vociferous ovation.

Tonight, the pianist played in every work on the program, commencing with Beethoven’s Trio in B-flat major for Clarinet, Cello, and Piano, Op. 11 (1797) for which she was joined by the Spanish clarinetist Jose Franch-Ballester, and cellist Gary Hoffman, whose leap to prominence followed his 1986 win of the Rostropovich International Competition in Paris. Together, the three musicians filled Beethoven’s score with vibrant musicality.

The timbres of the three ‘voices’ aligned perfectly, and rhythmic clarity was a hallmark of their performance. Dramatic accents cropped up in the opening Allegro con brio, to which a pensive interlude brings contrast.

A waltz-like motif for the cello is taken up by the clarinet in the Adagio: a fine opportunity to savor the coloristic gifts of Mssrs. Franch-Ballester and Hoffman. Ms. McDermott brought gentley nuances to the mix, and, after a slightly darker passage, her delicacy of touch underscored Mr. Hoffman’s graciously expressive softness of melody.

The trio’s finale is a theme-and-variations affair which gets off to a perky start. The first variation brings some elaborate piano passages, the second a cello/clarinet duo, and the third is fast and fun. After veering into minor mode for the fourth variation, the music proceeds to a passing about of the theme, a petite marche, some tickling trills from the keyboard, and a witty finish.

The concert’s centerpiece was a vivid performance of Igor Stravinsky’s L’Histoire du soldat (The Soldier’s Tale), in the trio version for violin, clarinet, and piano (1918, arranged 1919), Mr. Franch-Ballester brought two clarinets to the stage for this work, which commences with The Soldier’s March, filled with jaunty swagger and relentless piano. A bouncing piano figuration introduces The Soldier’s Violin, wherein Ida Kavafian’s bow dances across the strings, and the clarinet provides a sense of jollity. The music seems about to fade away until it hits a punctuating chord.

A Little Concert brings swirls of notes, the piano rhythm pulsing along. The music has an ironic feeling, and turns insistent before its sudden end. A dance triptych (Tango, Waltz, Ragtime) finds Ms. Kavafian’s violin in waltzing mode, with rhythmic piano and commenting clarinet. The final movement of his colourful suite, The Devil’s Dance, has a wild streak. The three musicians seemed truly to enjoy playing this miniature masterpiece, which clocks in at a mere fifteen minutes but covers a lot of musical territory in its course.

Following the interval, Ms. McDermott had the stage all to herself with some marvelous Mendelssohn: selections from Lieder ohne Worte (Songs Without Words). She chose numbers 1, 2, and 3 from the cycle which made for a nicely contrasted segment of the program. Her playing was both elegant and passionate, and her mastery of dynamics was very much to the fore.

Bedřich Smetana’s Trio in G-minor for Piano, Violin, and Cello, Op. 15 (1855, revised in 1857) was written in memory of the composer’s four-year-old daughter Gabriela, who succumbed to scarlet fever in 1854.

Thus, the work begins with Ida Kavafian’s playing of a violin solo of yearning tenderness, with a rise in passion which subsides to a cello theme and an ascending phrase for the violin. Suddenly, a forward impetus springs up, and the music gathers steam to a grand outburst. Following a brief violin cadenza, the string players introduce a buzzy agitato, over which Ms. McDermott plays some sparkling piano passages. The music grows rhapsodic, and grand passions burst forth before Mr. Hoffman’s lyrical cello and Ms. Kavafian’s shining violin conspire to play on our emotions. The Moderato assai comes to an emphatic, passionate conclusion.

Bustling, almost furtive strings lend a scherzo-like feeling to the start of the second movement. Melodic motifs sing forth, building to grandeur before finding a quiet place to conclude. The three musicians dig in for the final Presto, for which Ms. McDermott sets a fast pace. In a reflective mood, Ms. Kavafian and Mr. Hoffman have appealing solo passages, and the pianist a thoughtful interlude.

Now some fast plucking takes over, and the music dances along for a bit. But a calmer mood returns, with the music going deep. The trio ends grandly, with an affirmative air of hope springing from the ashes of tragedy.

~ Oberon