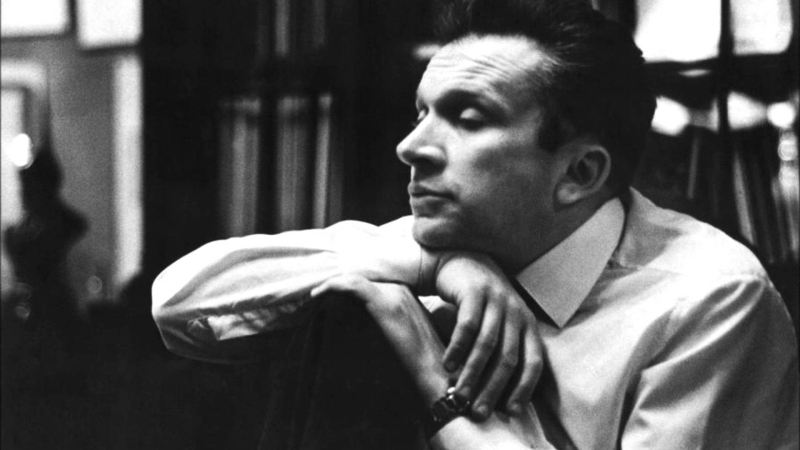

Above: composer Mieczysław Weinberg

~ Author: Ben Weaver

Sunday February 29th, 2018 – Leon Botstein and his American Symphony Orchestra always present interesting programming of rarely-performed works. On January 28th, the theme was “Jews in Soviet Russia after the World War” and was perhaps one of their finest concerts. Presented were three works by two composers: first half was dedicated to Mieczysław Weinberg and second half to Vieniamin Fleishman. Both men were close friends with Dmitri Shostakovich, whose influence can be heard in their works.

Mieczysław Weinberg is perhaps the better-known of the two. Born in 1919 in Warsaw, Poland into an artistic family (his father was a conductor and composer of the Yiddish theater and his Ukrainian-born mother was an actress.) During the war his parents and younger sister were interned in the Lodz ghetto and died in the Trawnicki concentration camp. After the war, in the Soviet Union where he settled, Weinberg was arrested by the KGB in 1953. Shostakovich’s personal appeal to Lavrenti Beria – and Stalin’s death soon thereafter – saved Weinberg’s life. Weinberg’s vast musical output includes 22 symphonies, 17 string quartets, 9 violin sonatas, 7 operas, 40 film and animation scores (including for the Palm d’Or-winning film “The Cranes are Flying.”)

Leon Botstein began the concert with Weinberg’s “Rhapsody on Moldavian Themes,” composed in 1949. An ancient state – forced to be one of the Soviet Union’s republics between 1940 and 1991 – Moldavia’s culture is closely related to Romania’s and it’s folk melodies sometimes will bring to mind folk melodies Brahms and Dvořák used in their famous collection of dances. Weinberg’s Rhapsody begins with a drive from the low strings and then an oboe introduces the first mournful theme. The Rhapsody moves easily between the mournful and infectious dance tunes, alternating soaring full string section and solos for individual instruments. There is a definite Klezmer dance tune near the end, which brings the work to an exciting close.

Weinberg’s substantial Symphony No. 5, composed in 1962, without a doubt takes inspiration from Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 4, which though it was premiered in 1961 was composed 25 years earlier, and Weinberg and Shostakovich used to play a two piano arrangement of it for friends long before the premiere. The work opens with a slow “siren,” two repeated notes, from the violins. This motif returns over and over throughout the symphony like a wail of doom, sometimes picked up by other instruments. There are sudden interruptions from the timpani, bringing to mind Mahler’s 6th Symphony. There are beautiful and beautifully-played solos for various instruments, most notably the flute (Yevgeny Faniuk is listed as principal flautist) and horn (Zohar Schondorf)). The Symphony ends with a hushed march, growling trombones and a mysterious celesta.

Veniamin Fleischman was born in 1913 and entered the Leningrad Conservatory in 1939. His teacher, Shostakovich, called Fleishman his favorite student. While a student, on Shostakovich’s suggestion, Fleishman began composing the opera “Rothschild’s Violin,” from a short story by Chekhov. (Fleishman wrote his own libretto.) When the Nazis invaded the USSR in the summer of 1941 Fleishman enlisted in the Red Army and was killed on September 14 near Leningrad. Shostakovich went to great lengths to retrieve Fleishman’s manuscript of the opera. He completed and orchestrated the work in 1943-44, and later went to great lengths to have it performed, though without much success. Its sympathetic portrayal of Jewish people no doubt did not fit comfortably with the Soviet regime. There was one concert performance in Moscow in 1960 and a staged performance did not take place until 1968. Shostakovich wrote in his memoirs: “It’s a marvelous opera – sensitive and sad. There are no cheap effects in it; it is wise and very Chekhovian. I’m sorry that theatres pass over Fleishman’s opera. It’s certainly not the fault of the music, as far as I can see.”

The main character, a Christian coffin maker Yakov Ivanov, undergoes a spiritual crises and something of an awakening. After Yakov’s wife Marfa informs him that she is dying, they both reminisce about their dead child, and Yakov realizes he will have to build his own wife’s coffin. “Life is all loss, only death is gain,” he says. Though Yakov quarrels with Rothschild, the young flautist in the local Jewish orchestra, at the end he leaves Rothschild his most prized possession: the violin, which Rothschild begins to play as the opera ends.

“Rothschild’s Violin” is a magnificent opera. Fleishman, editing Chekov’s story, brilliantly removed all secondary characters and stories, keeping only the story of the coffin-maker. We know nothing even about the young Jew to whom Yakov leaves his violin; nor about Yakov’s wife Marfa, who is dying. This is a story of one man, there are no loungers or pauses in the narrative. It moves quickly through monologues and dialogues, only pausing for Yakov’s final apotheosis where he comes to understand his life and losses. Though the characters, especially Marfa, feel sorry for themselves, there is no sentimentality or cheap dramatic effects. The simplicity of it is what gives the work so much power.

The quartet of singers assembled for the opera was perfect. Bass Mikhail Svetlov (above) was a deeply moving and beautifully sung Yakov. The only native Russian speaker in the cast, he projected the text and all its nuances in a way few can. His is a big, rich voice, with an easy top.

Mezzo-soprano Jennifer Roderer (above) was a plum-voiced Marfa; managing to be both a nagging self-pitying wife and a woman who, perhaps on her deathbed, has obviously suffered so much. What kept flying through my head as she was singing is that Ms. Roderer’s large, beautiful and booming mezzo would make a fantastic Fricka; it is a role she sings and we can only hope she is able to sing it at the Metropolitan Opera (which is supposed to bring back its Ring cycle soon.)

Tenor Marc Heller (above), singing the role of the leader of the Jewish orchestra, would make a pretty good Siegfried. The huge, ringing voice flew easily over the orchestra and Maestro Botstein’s rather unforgiving volume.

Lyric tenor Aaron Blake (above) was a lovely and nervous young Rothschild. There is actually very little for Rothschild to sing, so Mr. Blake made up for it with pantomime acting, particularly at the end after Yakov has gifted him his fiddle (kindly loaned for the proceedings by a violinist on stage), and an extended orchestral postlude (including lovely solo violin playing by concertmaster Gabrielle Fink) summarizes not only Yakov’s sacrifice, but Rothschild’s future. Intentionally or not, there was something quite poetic and moving in the fact that a member of the orchestra gave up her violin and was not able to play the extended orchestral passage in the end, mirroring Yakov’s own losses.

It is also worth nothing that the final orchestral passage goes from being lightly scored and transparent to having a very close resemblance to the searing final moments of Shostakovich’s 5th Symphony.

“Rothschild’s Violin” is a great opera; it deserves to be staged.

~ Ben Weaver