Above: Anna Netrebko as Tatiana

Author: Ben Weaver

Saturday April 22nd, 2017 matinee – Tchaikovsky’s operatic adaptation of Pushkin’s “Eugene Onegin” arrived this Spring at the Metropolitan Opera. Today, the season’s final performance of the opera was telecast via HD to cinemas around the world. It’s a practice that has been contributing to the hemorrhaging of live audience attendance for the house. The Met auditorium has countless empty seats more often than not, and many of those that are filled are actually papered and subsidized by donors. Today’s ONEGIN matinee was one of only two performances of the opera that actually sold out.

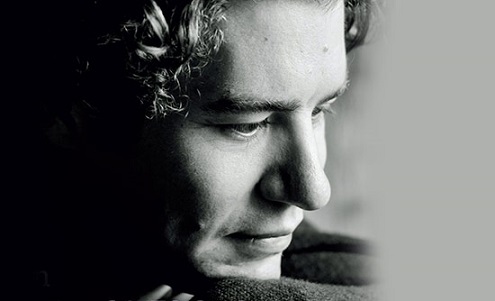

In the pit was the English conductor Robin Ticciati (above). He led a really magnificent reading the score, the Met Orchestra responding to Tchaikovsky’s superb orchestration with perfection. Ticciati was careful not to overwhelm the singers with sound (Tchaikovsky’s orchestral writing is often dense). There was a wonderful lightness to his interpretation, each musical strand rising magically out of the tapestry of sound. His energetic, forward moving pacing mostly worked well. Perhaps if Tatiana in her Letter Scene and Lensky in his Act II aria had been allowed to linger just a tad longer…but overall Tchaikovsky’s magical score danced and sighed superbly.

The cast assembled for the revival of this 2013 production was first rate. At the heart of it was Anna Netrebko as Tatiana. When Netrebko first sang the role at the Met in 2013 I did not think she made a great impression. Primarily I objected to her bland reading of the text, disappointing for a native speaker. She has certainly been able to deepen her understanding of the role. This afternoon she was a living, breathing heroine. Her Letter Scene was by turns wistful and sad, excited and terrified. Fear as she awaits Onegin’s arrival, and shame at his rejection, were palpable. Haughtiness, in a crimson gown at the royal ball in Act III as she sees Onegin for the first time in many years, was delicious. And the final scene revealed verismo-ish declarations that she will not betray her husband. I suddenly remembered that Netrebko has sung Lady Macbeth and intends to sing Tosca too. These flashes of pure steel were thrilling. Vocally she was excellent. There are occasional tendencies (not new to her) to stray off pitch in her middle voice. But her top was strong and gleaming, and the aforementioned steel in the final scene brought to mind Galina Vishnevskaya. The young, impressionable Tatiana is a woman now, royalty even. She won’t let Onegin forget this.

Peter Mattei as Onegin (above) was in stunning voice. Truly this is one of the most beautiful baritone sounds in the world. Soft and plush, but not lacking in volume. Mattei’s long-limbed figure undergoes a reverse transformation of Tatiana. Haughty and indifferent at first, he unravels as Tatiana grows in stature. While Mattei’s singing was beyond reproach, his Russian diction was quite poor. In Act 1 it was still recognizable as Russian. Alas, as the opera progressed I often wasn’t sure he was singing in Russian at all, or just making sounds intended to sound vaguely Slavic.

Russian tenor Alexei Dolgov was a terrific Lensky. His singing is effortless. Perhaps his neurotic, bordering hysteric Lensky would not be to all tastes, but it was believable, and – again – the singing was terrific. His Act II aria was heart-wrenching; his Russian diction crystal clear. Elena Maximova, as Lensky’s fiancée Olga, did everything right dramatically and musically. Perhaps the voice is a bit too monochrome and lacks warmth, but during the Act II ball she wonderfully conveyed a flirty, young woman who only too late realizes that her behavior towards her fiancée will lead to tragedy.

It is a great touch to have a young bass play Prince Gremin. Usually Gremin is seen as an old man, but a youthful Stefan Kocan, with the necessary low notes in full bloom, leaves no doubt why Tatiana would refuse to leave him for a now-pathetic Onegin.

It was wonderful to see and hear two veteran Russian mezzos as the matriarchs. Elena Zaremba as Madame Larina showed off a still gleaming, forceful mezzo, effortlessly dominating ensembles. The great Larissa Diadkova, long one of my favorite singers, was a superb Filippyevna. There is still much voice left and dramatically her fussy Nanny was by turns funny and deeply moving as she recalls her own youth. My first live Filippyevna was the legendary Irina Arkhipova making a much belated Met debut in 1997. It is the highest compliment I can pay Diadkova to say that she is in the Arkhipova stratosphere of artists.

There were wonderful supporting appearances by Tony Stevenson as Triquet (lovely singing of the birthday song; it’s a character that can be very grating, but Stevenson is a superb character singer/actor), Richard Bernstein as Zaretski, and David Crawford as a Captain. The chorus was in excellent form, under the leadership of Donald Palumbo.

The big problem with the Met’s ONEGIN, alas, is the mediocre-to-terrible production by Deborah Warner, sets by Tom Pye, costumes by Chloe Obolensky and lighting by Jean Kalman. Warner’s boring conception is old-fashioned in the worst sense of the word. I’m as fond of a “period appropriate” production as anyone, but Warner’s staging contributes nothing to the work. The previous, gorgeous production by Robert Carsen showed more depth with a simple white box and autumn leaves than Warner and team manage with stuffy period detail. The silly “when in doubt, just lay down on the stage” trope should be made illegal. All of Act I is set in the Larin country home living room. Why the family would bring their entire farming staff in there, and then allow people to throw wheat on the living room floor, is a mystery. The Duel scene is the most effective, a moody wintry landscape. But the columns in all of Act III are simply too large, sitting like titans, distracting from any and all action on the stage.

So it was the superb cast of singing actors, the orchestra, and thrilling conducting by Ticciati that made this ONEGIN a superb musical event.

~ Ben Weaver