Above: performance photo by Brandon Patoc

~ Author: Mark Anthony Martinez II

Saturday April 26th, 2025 – The New York Philharmonic played a fantastically curated concert of Mozart and Bartók. Although the throughline of the pieces isn’t immediately apparent, the pairing of Mozart at his most theatrical — with the Magic Flute Overture and his Fifth Violin Concerto — with Bartók’s The Wooden Prince, originally written as music for a ballet, made for a fantastic night of music.

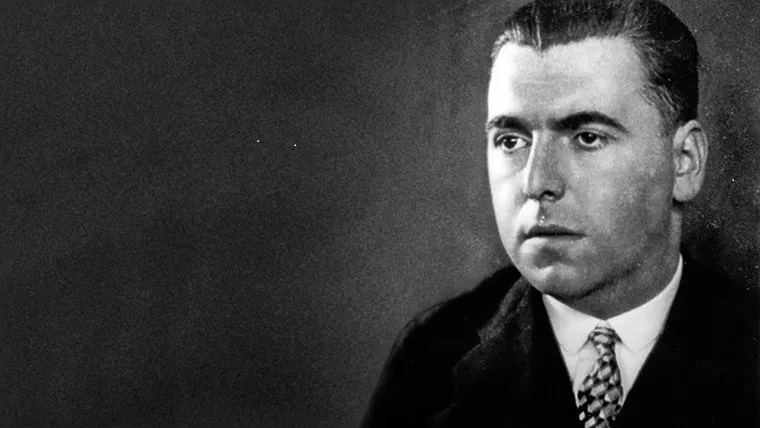

The guest conductor was Iván Fischer, and he conducted marvelously: at ease in the music while simultaneously seeming to really have fun. Maestro Fischer appeared to conduct The Magic Flute Overture from memory at the podium, moving through the different sections of the piece with wide arm gestures.

I had just recently seen The Magic Flute at the Metropolitan Opera the week before, so the piece was still fresh in my memory. Something very interesting was that, when I heard it that night at the Philharmonic, the overture seemed more like a symphonic suite than an overture to a stage play. It seemed more related to Mozart’s Jupiter Symphony somehow in this moment, rather than the opening to Così fan tutte. The music was played perfectly, with every dynamic crystal clear in execution. Maybe it was the perfection of how the piece was played that made it seem more symphonic and less like a piece written for the stage, where inevitably something new happens every night.

I particularly liked the restraint that Maestro Fischer (above, photo by Brandon Patoc) showed in the moments of the overture where silence mattered more than sound, such as the callback to the brass opening punctuated with long rests. The rests seemed longer than usual, but the impact was memorable because of it.

The audience gave a very warm and deserved applause, after which the orchestra reduced in size to prepare for the violin concerto.

The soloist, Lisa Batiashvili (above), came out in a very memorable bright yellow dress with a baby blue sash around her waist. Normally, I don’t notice what soloists wear in performances, but this outfit seemed too intentional, almost as if it were making a statement. I thought that the color scheme seemed coincidentally similar to the Ukrainian flag until I saw a giant brooch of the U.S. Stars and Stripes cinching the sash onto her. So whatever the intent was, I’m sure it meant something to those more sartorially inclined.

Batiashvili played the Mozart with clear familiarity with the style and music. Normally, I feel soloists tend to lean into the fiery, show-stopping nature of concertos, but Batiashvili tended toward austerity and restraint in her playing for the first two movements. The piece was played in a way that seemed courtly: certainly pleasant, but not too forward to draw attention to itself. Things changed when Batiashvili reached the cadenza of the first movement. The cadenza started out seeming to be in a Mozartian style, then veered into the chromatic and atonal. It wasn’t bad by any means, and certainly showcased Batiashvili’s virtuosity. It was just surprising to hear something so very non-classical in such a quintessentially classical piece. I read the program afterwards and saw that the cadenza was composed by a 15-year-old Georgian composer named Tsotne Zedginidze, which made quite a lot of sense in hindsight.

I quite enjoyed the unconventional cadenza because it made me look forward to hearing the other cadenzas, which were also newly composed, one of them by the soloist herself. The other cadenzas were more traditional in nature though, which maybe was a good pairing with the one anachronistic one.

The third movement was where Batiashvili took off and seemed to have the typical soloist verve. I had never heard the finale of this concerto before, and I loved the effects that gave the whole piece the moniker of “Turkish.” The sections where Batiashvili played the more exotic melody and the strings played col legno seemed like a vision into the future of where classical music would head with early Romanticism. The sections sounded more like Mendelssohn in one of his symphonic overtures rather than Mozart, and I was thrilled to hear it.

After the concerto, Batiashvili gave several curtain calls, and it seemed like there was going to be an encore, but in the end, one didn’t come.

Before the concert began, I overheard some audience members chatting and wondering why the screen normally used for super-titles for lyrics was open. Another audience member joked that it was just so they could make sure to tell people to silence their cell phones before the show.

During intermission, the size of the orchestra ballooned, and it was almost impossible to fit more musicians on the stage. Before he started the Bartók piece, Maestro Fischer gave a short introduction. He told the audience that the piece was originally written for a short ballet, and — in an unconventional but amazing idea — had the original stage directions for the ballet projected onto the aforementioned screen while The Wooden Prince was being played.

This piece was another first for me, and it was truly a masterpiece. The piece starts with a humming sound that almost feels like what you’d expect from a movie showing deep space.

The story of The Wooden Prince follows a prince who falls in love with a princess, who is guarded by a fairy. The prince is blocked from being able to see the princess by the fairy, who enchants the forest in which they are to physically prevent the prince from reaching her.

The stage directions were such a wonderful idea because they showed where Bartók’s mind went when he was creating the music for each physical gesture. At first, I thought there were going to be instruments tied to each of the characters, but in the end, the entire orchestra was involved in every scene to provide complete sonic storytelling.

I found myself thinking about how The Wooden Prince compared with some of the other great ballets, like Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake and Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring. The conclusion I came to was that The Wooden Prince was uniquely its own masterpiece.

~ Mark Anthony Martinez II

(Performance photos by Brandon Patoc, courtesy of the NY Philharmonic)