Above: Maestro Raphael Jiménez with the Oberlin Orchestra at Carnegie Hall; photo by Fadi Kheir

Author: Brad S Ross

Friday January 20th, 2023 – On Friday evening, New York audiences were once again treated to a fine performance by the Oberlin Orchestra and Choral Ensembles as they returned to Carnegie Hall for the first time (publicly, anyway) since January 19, 2019. They were conducted by Oberlin Orchestras Director Raphael Jiménez, who led the performers in a unique program that included one repertory standard, one New York City premiere, and one buried gem.

The evening began with long—very long—opening remarks by Oberlin College and Conservatory President Carmen Twillie Ambar and Oberlin Conservatory Dean William Quillen.

Ambar’s remarks focused on two of the evening’s headlining pieces having been written by minority composers and therefore made all the requisite extollations about the need for representing historically marginalized groups. As important as this message is, it would be nice to hear the music of under-appreciated composers like Will Marion Cook, William Dawson, Florence Price, George Walker, etc., without this ever-obligatory preamble. My continued hope is that someday we will be able to let their music simply speak for itself.

Quillen’s remarks, while less political, were a seemingly endless list of “thank you”s, not unlike an Oscar acceptance speech—only this time, there was no hope of the music playing him off. All the parents and staff in attendance no doubt appreciated the acknowledgements, but after a full quarter hour of talking I was getting pretty antsy for things to move along.

Nevertheless, once the opening remarks concluded, the Oberlin musicians were finally able to grace the Isaac Stern Auditorium with their abilities—and what a pleasure they were to hear!

First on the program was Johannes Brahms’s Tragic Overture, Op. 81, from 1880. There’s not much one can say about this work that hasn’t already been expressed over the last one hundred and forty years, so I won’t labor on it here. It’s a pleasant and undemanding symphonic poem, lasting about fourteen minutes and chock-full of the lyrical gestures typical of that Romantic master. Needless to say, the Oberlin musicians tackled the piece expertly, but it did leave me wanting to hear more of their technical skills.

I was not left wanting for long, however, as the second work of the evening—the New York premiere of Iván Enrique Rodríguez’s A Metaphor for Power—immediately livened up the proceedings.

Written in 2018, A Metaphor for Power is a single-movement essay for orchestra lasting about thirteen minutes. Rodríguez—a 32-year-old Puerto Rican native—composed the piece as a comment on the turbulence and inequalities of contemporary life in the United States, despite the promise of its founding (the title, indeed, comes from a quote by James Baldwin). His use of social commentary through music was much more subtle than that of other recent protest works, however (Anthony Davis’s quite overt You Have the Right to Remain Silent comes to mind), making for a composition that was both cleverly referential and electrifying to hear.

The music opened with a bang before quickly diminuendoing into dream-like textures, complete with harp, mallets, and woodwind writing that sounded as though they had descended straight from Maurice Ravel’s Daphnis et Chloé. A contemplative middle section featured, among other memorable effects, distorted quotations from “America the Beautiful” and unsettling vocalizations from the orchestra as they recited overlapping lines from the Declaration of Independence. A great crescendo announced the beginning of the third, final section, which was marked by dramatic gestures that were almost filmic in execution. It all came to an energetic and wickedly engaging ending that lit up the room with excitement.

Above: Maestro Jiménez and composer Iván Enrique Rodríguez take a bow; photo by Fadi Kheir

The composer practically leapt from his seat and ran to the stage to share an emotional embrace with Jiménez before they took their bows together. The moment was as touching as it was well-earned. The composer having been unknown to me until that evening, I must say that I look forward to hearing much more from him in the future.

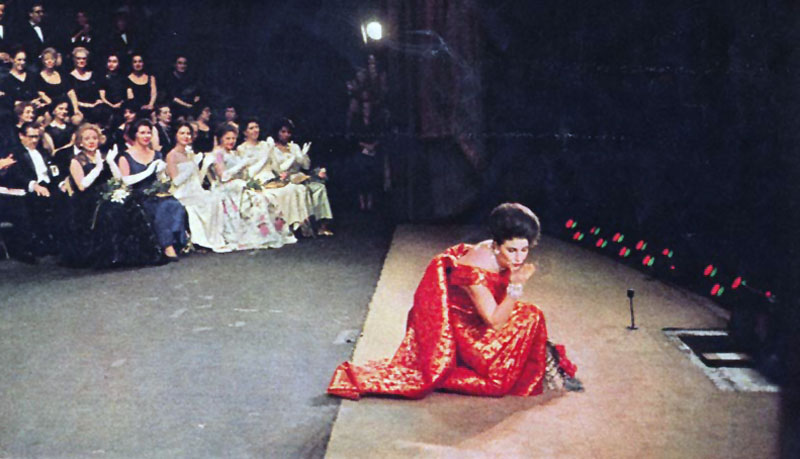

Above: the vocal soloists for the Dett oratorio: Chabrelle Williams, Ronnita Miller, Limmie Pulliam, and Eric Greene; photo by Fadi Kheir

The final and most substantial work of the evening was Robert Nathaniel Dett’s oratorio The Ordering of Moses. Dett, a Canadian-born American composer of the early 20th century, became the first black man to graduate with a double major from the Oberlin Conservatory in 1908. He initially wrote The Ordering of Moses as a thesis project while completing his Masters of Music from the Eastman School of Music in Rochester in 1932. Dett later revised and expanded the work, however, and it was premiered in its final form by the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra under Eugene Goosens in 1937.

Clocking just under an hour, the oratorio is divided into nine sections and is cast for orchestra, chorus, and four vocal soloists. Joining the Oberlin musicians for this performance were soprano Chabrelle Williams, mezzo-soprano Ronnita Miller, tenor Limmie Pulliam, and baritone Eric Greene.

Above: soloists Ronnita Miller and Eric Greene; photo by Fadi Kheir

The first section opened on warm instrumentation that favored the lower voices of the orchestra. A lone cello voice emerged for an occasional solo before Greene’s sonorous tones took center stage as “The Word,” describing the bondage of the Israelites under the Pharaoh. He was joined briefly by Miller, who cried out for mercy as the voice of the Israelites. The music was rather languid here, until a great exclamation of “Mercy, Lord” announced an upbeat transition into the second section, “Go Down Moses.”

A recent last-minute Metropolitan Opera debutant, tenor Limmie Pulliam (above, in a Fadu Kheir photo) then entered as the voice of the reluctant Moses, who is given the famous command by God, “Go down Moses, way down in Egypt’s land; tell Pharaoh: ‘Let my people go!’” (this section featured a particularly cheeky musical joke where Moses sings “I am slow of tongue!” at the most sluggish pace imaginable). The drama then moved fairly seamlessly into the third section “Is it not I, Jehovah!” as God affirms his edicts to Moses.

This was followed by a mostly uneventful instrumental interlude as the story was transported forward to Moses’s parting of the Red Sea (“And When Moses Smote the Water”). This exuberant, celebratory section was followed by two more instrumental interludes: “The March of the Israelites through the Red Sea” and “The Egyptians Pursue.” The former was an almost jaunty affair, complete with military snare and wordless chorus, while the latter featured brassy blasts and dramatic descending runs as the crashing waters swept away the pursuers.

Above: soprano Chabrelle Williams; photo by Fadi Kheir

Ms. Williams’s soaring vocals finally entered the proceedings in the waltz-like “The Word,” as the Israelites jovially sang praises to Jehovah. All forces joined for the triumphant finale “Sing Ye to Jehovah,” as the oratorio built to a final satisfying tutti instrumental blast.

Everyone performed splendidly throughout and the piece was met with one of the most enthusiastic standing ovations I’ve seen in a while, yet I couldn’t help feeling slightly underwhelmed by the music itself. Considering the scale of forces at work, the writing was not terribly economical. The instrumentation was often sparse and seldom were all of the elements brought together for fuller effect. The solo parts also heavily favored the male voices, leaving Williams and Miller very little to do for most of its duration.

This isn’t to say it was bad—far from it—, but it did leave me wanting a little bit more. Had Dett not died of a heart attack at the relatively young age of 60 in 1943, one cannot help but wonder what other and more exciting large scale works he might have brought to the concert hall. Nevertheless, it was exciting as always to hear a buried musical gem such as this get dusted off and given new life. It was a grand conclusion to another memorable concert by the Oberlin Conservatory musicians, who will hopefully return again soon to grace New York City audiences with another memorable program.

All performance photos by Fadi Kheir.

~ Brad S Ross