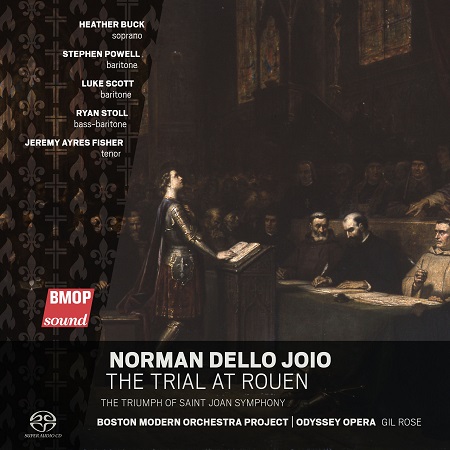

Above: soprano Heather Buck

Boston Modern Orchestra Project (BMOP) and Odyssey Opera have just released a recording of Norman Dello Joio’s 1956 opera The Trial at Rouen.

Actually, Dello Joio had been inspired even earlier by the story of Joan of Arc, writing an opera about her that he later came to feel did not do the subject justice. Nevertheless, drawing from that now-forgotten work, he prepared a symphonic adaptation, entitled The Triumph of Saint Joan, in 1951, which enjoyed considerable success.

This orchestral work opens the current recording; the piece is presented in three movements. The first, The Maid, has a pensive, darkish start. The music soon takes on a cinematic feel – which will be sustained throughout the entire work. Quietened, the gentle voices of flue and oboe mingle, with strings providing a lyrical counter-song. The music turns lilting, then animated. Brass voices arise, and a feeling of grandeur evolves. After a full stop, a brooding passage gives way to a rustic episode. A deep pulse leads on to a somber finish,

The second movement, The Warrior, opens with timpani and summoning brass. A beat springs up, woodwinds swirl, and the horns sing out: we are on the march. Rhythmic variety and mixes of instrumentation sustain us to another full stop. Insistent brass motifs then carry on to an epic finish.

The work culminates with The Saint, introduced by gentle winds in sorrowing mode. The flute sings a forlorn tune; the mood is pensive with an ominous undercurrent. A clarinet solo leads to a more propulsive passage, which calms. The music slowly recedes, like a memory, with a haunting final chord.

Feeling a strong connection to the subject matter, the composer wrote a new opera, The Trial at Roeun, in 1956 on commission from the NBC Television Opera Theatre. Of this work, Dello Joio wrote: “The Trial at Rouen is not a version of my first opera but is a completely new statement, both musically and dramatically; though the temptation to use the old material was great.”

The seventy-five minute opera, in two scenes, premiered to a large television audience in 1956, but was thereafter neglected. The opera was never performed in a live theatrical setting until BMOP and Odyssey Opera staged it in 2017.

The performers in The Trial at Rouen are soprano Heather Buck as Joan, baritone Stephen Powell as Pierre Cauchon, bass-baritone Luke Scott as Father Julien, bass-baritone Ryan Stoll as The Jailer, and tenor Jeremy Ayres-Fisher as A Soldier; Gil Rose is the conductor.

The opera opens with a prelude (apparently omitted for the televised version), which commences with gentle winds and strings and slowly builds to fanfare-like brass. The pleasing voice of tenor Jeremy Ayres Fisher as the Soldier is heard, at first tra-la-la-ing; his song soon becomes one of longing for home. The tenor is joined in sung dialogue by Father Julien (Luke Scott – another handsome voice). We hear “the Maid” mentioned, and of their concern for her; crystal clear diction from both men enhances their singing.

Now we meet Joan’s nemesis, Pierre Cauchon, the English-leaning Bishop of Beauvais, portrayed by Stephen Powell. The Bishop and Father Julien have a chant-like passage, after which we can relish Mr. Powell’s beautiful tone (this singer has long been a great favourite of mine). The Bishop expects Joan to recant her claim that she has been hearing voices from Heaven, and to don female garb as a symbol of her capitulation.

The Jailer (Ryan Stoll, yet another fine voice) attempts to force himself on Joan, but Father Julien comes to her rescue. The kindly Father advises the girl to put on the dress, in deference to the Inquisitors. Now we hear the lovely lyrical soprano of Heather Buck, who in Joan’s music shows both the assurance and the vulnerability of the character in perfect measure.

Mr. Scott as Father Julien makes a highlight out of “O good Maid, my heart is with you.” This turns into a duet with Ms. Buck, which becomes quite dramatic. Both singers relish the composer’s melodic line, and his orchestration deftly underscores their singing. Their voices join in a call to Christ.

Now Ms. Buck has an evocative solo, “Are you the price of life’s sweet breath?“, which is sung to the dress she has been told to wear. Ms. Buck’s vivid vocalism becomes urgent, before turning poignantly reflective; then a hushed postlude marks the end of the opera’s first scene.

Scene 2 is the trial itself. After a somber prelude, a sonic outburst announces the crowd, demanding to be let in to the proceedings. Mr. Powell and Ms. Buck now have a great deal of singing to do, and both are admirable. Mr. Powell’s diction is perfect as he scolds the crowd and instructs the inquisitors. He then sings – magnificently – “I Call on Thee, Eternal God” – which could enter the solo baritone repertoire as a free-standing aria. Powell’s rendering of it is thrilling, and as the chorus joins him at the end…perhaps the most ‘operatic’ passage of the work.

Joan is led in, in chains, and the crowd seems sympathetic to her plight. Powell, as Cauchon, begins to interrogate her, saying her sin is heresy. Ms. Buck, as Joan, sings “In Our Time of Trouble“, recalling her childhood; the soprano’s dynamics and verbal inflections are soothing. Cauchon then poses a question: “Was Saint Michael clothed when he appeared before you?” As he baits her further, a propulsive beat develops. The chorus calls on the Maid to repent.

Joan states that she does not know why she was “chosen”; as tension builds, she calls on God to come to her aid. Cauchon summons the executioner and – to an eerily bouncy rhythm, rather daemonic – says Joan is condemned to death and will be burned.

Joan begs to be spared a fiery death; Ms. Buck excels here, asking why God has abandoned her. Then, recalling her glory in battle, the soprano soars to a high climactic tone.

The Maid becomes desperate, but – after a full stop – offstage a cappella voices sing “Be brave, daughter of France!” Joan recants, but Cauchon rejects her words. After Joan’s high-lying phrases of defense, Cauchon consigns her to Hell. The victim speaks pleadingly, “Jesus…my Jesus!”

Ms. Buck now has the final moments of the opera to herself, making a beautiful effect with “Your final will be done“: an aria of resignation which gives way to Joan’s transfiguration. A timpani beats quietly, and the music fades away.

The excellence of the recording, and its impressive cast, put The Trial at Rouen in the best possible light; it’s an opera that deserves to be widely heard. For me, “cinematic” remains the word that best describes the music, and the roles of Joan and Cauchon provide ample opportunity for the human voice; Ms. Buck and Mr. Powell have set the bar high for future candidates.

To purchase the recording, go here.

Listening to The Trial at Rouen, I was recalling meeting soprano Heather Buck while I was working at Tower Records a few years ago. She was then a young singer seizing her first career opportunities; we had a very nice chat. In the ensuing months, I would sometimes see her on the train going home, always with a score on her lap, singing to herself.

~ Oberon