A performance of Richard Wagner’s SIEGFRIED IDYLL by the Toronto Symphony Orchestra conducted by Peter Oundjian.

Watch and listen here.

A performance of Richard Wagner’s SIEGFRIED IDYLL by the Toronto Symphony Orchestra conducted by Peter Oundjian.

Watch and listen here.

German soprano Uta-Maria Flake (1951-1995) sings “Träume” from Richard Wagner’s Wesendonck-Lieder; her interpretation is rather unusual, but I like it.

Listen here.

“Ms. Flake studied at the Hamburg University of Music and, as a scholarship holder of the Hamburg State Opera, at Indiana University in Bloomington (USA). Further training by Tito Gobbi in Florence and by Mario del Monaco in Lancenigo. As early as 1971 she took part in a television recording of Offenbach’s ORPHEUS IN THE UNDERWORLD from the Hamburg Opera. In 1973 she won first prize in the national singing competition, and in 1974 she was a prizewinner at a concours in Montepulciano. She began her actual stage career in 1975 at the Stadttheater in Ulm, where she made her debut as Leonora in Verdi’s FORZA DEL DESTINO. From 1976-80 she was a member of the Dortmund Opera House. Here in 1979 she sang Eve in the German premiere of the opera PARADISE LOST by Penderecki; this was followed by guest appearances in this role at the Munich State Opera, at the Warsaw Opera and (in concert version) at the Salzburg Festival. From 1980-83 she was engaged at the Staatsoper Stuttgart, where she sang her great roles: Beethoven’s Leonore and Weber’s Agathe, Wagner’s Elsa and Eva, and Offenbach’s Giulietta.

She made successful guest performances at the State Theater in Hanover, at the Deutsche Oper am Rhein Düsseldorf-Duisburg, at the State Opera (as Lisa in PIQUE DAME) and at the Deutsche Oper Berlin (as Leonore), at the Covent Garden Opera London (as Elsa and as Freia), at the Teatro San Carlos Lisbon (Freia, Sieglinde, Gutrune and 3rd Norn), at the Cologne Opera House (Tchaikovsky’s Lisa), and at the Teatro Verdi in Trieste and at the Stadttheater in Basel as Sieglinde in WALKURE. Ms. Flake was also a concert soloist and lieder recitalist.”

Above: the Valkyries on the field of battle in the Teatro Colón’s abbreviated RING Cycle; Maestro Roberto Paternostro is on the podium

~ Author: Oberon

In 2012, the Teatro Colón in Buenos Aires presented the first performances of Cord Garben’s reduction of Richard Wagner’s monumental RING DES NIBELUNGEN; Garben cut the usual run-time of the complete Cycle from fifteen to seven hours, and meant his version to be performed in a single day. I’ve been watching it on DVD, finding it by turns intriguing and maddening.

The production was to have been directed by Katharina Wagner, great-grand-daughter of the composer. In the documentary film that is part of the boxed DVD set, Ms. Wagner arrives at Buenos Aires to start rehearsals and finds that the theatre is behind schedule in the creating of the physical production: sets, costumes, and wigs are not ready. Ms. Wagner decides she cannot work under such conditions. She flies back to Germany, but then returns to Buenos Aires…only to resign from the production.

Enter one of La Fura dels Baus’s director/choreographers: Valentina Carrasco. Described by soprano Linda Watson, who plays Brünnhilde, as a ‘spitfire fireball’, Ms. Carrasco and her team take matters in hand and – in just over a month of rehearsals – get the Colón RING stage-worthy. Meanwhile, there have been problems on the musical end of things, too: some of the originally-cast singers have dropped out, and conductor Roberto Paternostro becomes frustrated with the musicians of the Colón orchestra; the Maestro walks out of a rehearsal, calling their playing “a farce”. Somehow it all comes together, and the production is a hit – at least musically.

Ms. Carrasco’s key idea is introduced early in Rheingold; the Rhinemaidens appear to be nannies guarding their treasure: a baby. Bad idea? I thought so at first. But then, babies represent the future…the hopes and dreams of mankind. Alberich steals the ‘golden child’, and by scene three, the Nibelheim scene, he has set up a ‘baby factory’ to increase his ‘wealth’: in a combination torture chamber and nursery, women are continuously and forcibly impregnated, their babies cruelly snatched from them and kept under the eye of sinister nurses. Other pregnant women are seized on the streest and enslaved, giving the term “forced labor” a fresh meaning. It’s a hellish scene, reminding us of the horrors of THE HANDMAID’S TALE.

As the Cycle evolves, we continue to see children as pawns; separated from their parents by the State, the shadow of Trump’s Amerika looms large. And in Siegfried, Fafner keeps some kids in a cage. Talk about self-fulfilling prophecies…

But what about the story-telling? The musical flow? In Rheingold, the narrative is fairly clear, but the characters of Donner, Froh, and – unkindest cut of all – Erda are eliminated altogether. Jukka Rasilainen in his military uniform with medals and gold sash, is a Perónist Wotan. And Simone Schröder, as Fricka, wears her hair in one of Eva Perón’s iconic styles. The musical cuts are scattered; in interviews, the singers speak frequently of the production’s biggest challenge: remembering what has been deleted and what your next line will be.

There’s some really good, characterful singing in Rheingold: Andrew Shore brings with him a sterling reputation as Alberich on the world’s stages, and both Mr. Rasilainen and Ms. Schröder are fine. The Rhinemaidens – Silja Schindler, Uta Christina Georg, and Bernadett Fodor – fare well on a tricky set that includes a water pool and a sandbox; I like Ms. Fodor’s voice especially. Wotan follows Gollum’s example: to get the ring, he bites or hacks off Andrew Shore’s finger with the ring wrapped around it.

Stefan Heibach is a lyrical Loge; he wears a fedora, raincoat, and sunglasses. Kevin Conners excels as Mime – later, in Siegfried, he will excel his own excellence. The giants are impressively sung by Daniel Sumegi (Fasolt) and Gary Jankowski (Fafner), the latter confined to a wheelchair. They are accompanied by a band of young thugs, some wearing soccer togs. I half expected to see Klaus Barbie flitting in and of the Nibelheim torture chamber.

Musically, the first act of Walküre, one of the most perfect acts in the entire operatic repertoire, is hacked apart. The arranger is especially unkind to Sieglinde, which is unfortunate as the role is very finely taken by soprano Marion Ammann. Ms. Ammann is an excellent singing-actress, gamely entering into the director’s concept of the role: she is indeed her husband’s ‘property’, for Hunding has kept her tethered to the floor on a short rope with a rough noose around her neck. She has been unable to stand erect for such a long time that, when Siegmund sets her free, she can barely walk. Ms. Ammann’s vocalism makes the substantial cuts in ‘Der Männer Sippe’ all the sadder. Stig Andersen, remembered for his Met Siegfrieds in the year 2000, is an excellent companion to Ms. Ammann. The pulling of the sword from the tree seems like an after-thought here. Daniel Sumegi, a paunchy Hunding, wears a wife-beater t-shirt. He sounds creepy, and he plays the character as truly revolting. We feel no shred of sympathy for this Hunding.

Linda Watson as Brünnhilde doesn’t sing ‘Ho-Jo-To-Ho‘ to open Act II of Walküre; Cord Garben simply jumps from Wotan’s fantastic opening lines to mid-Wotan/Fricka duet. Ms. Schröder loses a lot of Fricka’s music but does well with that which is left to her.

Mr. Rasilainen navigates the cuts in Wotan’s monologue successfully – all too soon, it’s “Das ende.” Ms. Watson’s singing of the passage where Brünnhilde weighs Wotan’s new instructions is excellent, and beautifully filmed. The pursued Wälsungs arrive, and Ms. Ammann is really thrilling in this scene of Sieglinde’s guilt and her love for her brother; her singing is expressive and passionate. Mr. Andersen is moving in Siegmund’s lines throughout Act II. The weight of the world is on him; all he wants is to be with Sieglinde. He and Ms. Watson are very effective in the Todesverkündigung (‘Annunciation of Death‘) which is staged with heartfelt simplicity. Now the cuts come fast and furious. Hunding fells Siegmund, then lets his thugs kick the hapless man to death.

As Walküre moves to its conclusion, the production becomes truly affecting. The parting of Wotan and Brünnhilde is heart-rendingly intimate and beautifully acted by Ms. Watson and Mr. Rasilainen. After Wotan has kissed away his daughter’s divinity, she sinks to the floor. White-clad angels appear and surround her slumbering form with candles – a gorgeous image:

As the Magic Fire music plays, Mr. Rasilainen as Wotan removes his military jacket and other signs of his power and command; he almost seems to age before our eyes. As the music of Walküre reaches its solemn end, he walks slowly away from the glowing Valkyrie rock: the king of the gods is now the Wanderer.

As the applause welcoming Maestro Paternostro back to the podium for Siegfried fades, someone in the audience shouts “Viva Wagner!” I was feeling about the same at this point.

This Siegfried is populated by convincing singing-actors. Cord Garben’s cuts are judicious in this opera, probably the most difficult of the four to compress. We get just enough of the Siegfried/Mime banter, with tenors Leonid Zakhozhaev and Kevin Conners very much at home as hero and dwarf respectively. Much is made of the fact that Mime is both Siegfried’s father and mother – Mr. Conners dons a blonde drag wig to accentuate his maternal characteristics. Nothung is discussed – and later re-forged – but the riddle scene for the Wanderer and Mime is completely excised.

The horn-call and solo serve as in interlude, leading us to Fafner’s cave, where Act II centers on Siegfried and Fafner. The wheelchair-bound, drowsy giant is surrounded by his entourage while his child-slaves observe the action from behind bars. There’s a rumble; Siegfried wounds Fafner. Their ensuing dialogue is excellently voiced by Mr. Zakhozhaev and by basso Fernando Rado, who is credited as the Siegfried Fafner, even thought the fellow in the wheelchair looks a lot like Gary Jankowski, who sang the role in Rheingold.

In one of the production’s serious visual lapses, the Forest Bird appears as a furry green muppet. Silly. Wotan wanders in, aged and weary; Siegfried breaks his grandfather’s spear by hand, sending the old man on his way.

The candles are still glowing around Brünnhilde’s rock. Fortunately, the opera’s dumbest line – “Das ist kein mann!” – is cut. The ecstatic genius of Wagner at “Heil dir, sonne!” finds Linda Watson at her best; she maintains peak form as cuts carry her directly to “Ewig war ich“. Brünnhilde resists, so Mr. Zakhozhaev woos her with ardent, lyrical singing. Capitulation: “Radiant love! Laughing death!” Ms. Watson falls short of the high-C. It doesn’t matter. Together, the lovers blow out the last remaining candle. The audience bursts into massive applause.

One of my favorite RING scenes, The Norns, is cut altogether. Instead, Götterdämmerung opens with the Dawn Duet; the couple seem to be living in a balconied duplex apartment in the low-rent district. Both singers are excellent here, mining the lyricism of their vocal lines music and well-supported by Maestro Paternostro and the orchestra. Ms. Watson and Mr. Zakhozhaev have this music in their blood; the soprano creates another vocal high-point as she calls on the gods to witness her love for Siegfried.

At the Gibichung Hall, Mr. Sumegi is a chilling Hagen, and he has Gutrune (Sabine Hogrefe) and Gunther (Gerard Kim) completely under his thumb. Mr. Shore’s Alberich briefly menaces Hagen. Then Zakhozhaev/Siegfred strolls in; Sumegi/Hagen is impressive as he describes how the Tarnhelm works. Mr. Zakhozhaev sings the toast to his wife expressively, but he nearly chokes on the polluted potion. Once drugged, he kisses Gutrune passionately. Siegfried’s blood-brotherhood with Gunther is mentioned almost in passing, and the two men are off to secure Brünnhilde for Gunther as Ms. Hogrefe’s cuddly, adorable Gutrune anticipates her union with Siegfried. Mr. Sumegi’s deals darkly with Hagen’s Watch.

As the Waltraute scene is cut entirely, we remain at the Gibichung Hall; Brünnhilde, dressed in a very odd, constraining bridal gown, is led in like a dog by Gunther. The whole business of “…how did you get that ring?…” is quickly dispatched, and Brünnhilde goes wild, ripping off her wedding gown and over-turning furniture. There’s no “Oath”…just Brünnhilde, Gunther, and Hagen plotting in an exciting trio.

On a golf course, Siegfried practices his swing; no Rhinemaidens here, but some caddies instead. Jarred back to reality by another potion, Siegfried extols Brünnhilde. Hagen attacks him with a golf club. Mr. Zakhozhaev sings his tender farewell to his true wife. He dies a slow death, bleeding from the mouth. During the Funeral March, his body lies alone on the stage until at last he is borne away.

In the scene of Gutrune awaiting her groom’s return, Ms. Hogrefe is quite touching; she screams when Hagen’s deceit is revealed. Hagen bullies his siblings, finally fighting with – and killing – Gunther. Brünnhilde arrives, and explains the facts to Gutrune; the set slowly turns as Gunther is carried off.

Brünnhilde is alone with Siegfried’s body. The Immolation Scene, very effective in Ms. Watson’s interpretation, becomes an intimate rather than a public ceremony: the soprano’s singing of “Wie sonne lauter...” touched me deeply; as she sang, ‘angels’ covered Siegfried with a red shroud. A vision of Wotan appears, and he looks down on how things have played out; at “Ruhe, ruhe, du Gott!” the now-powerlessgod slowly withdraws.

The Rhinemaidens enter and receive the ring from Brünnhilde; Ms. Watson is exciting, polishing off her singing to powerful effect before joining Siegfried in his shroud. The angels re-appear with candles which they arrange around the lovers’ bodies. Now the populace fill the stage; the baby is restored to the Rhinemaidens, and all of the children who had been stolen from their parents rush on to be reunited as loving families. They stand, like humanity in all its glory, looking out into the future. It made me cry, actually, while also making me disgusted with the sadists who currently hold sway over our beloved country; may the gods deliver us from evil.

Linda Watson receives a mammoth ovation – she has won me over in the course of the presentation – and Mr.Zakhozhaev is strongly hailed, rightly so. Maestro Paternostro, all of the singers, and indeed everyone on the musical side of things are heartily cheered. The production team are booed, but – while not everything in their concept worked – they saved the day, and much of what they brought forth was thought-provoking, effective…and timely.

One of the most fun bits in the documentary about the preparation for the production is a brief scene in which soprano Sabine Hogrefe (who stepped in for Christine Goerke in a Met performance as Elektra earlier this year) and tenor Leonid Zakhozhaev are rehearsing the final passage of the duet that closes Siegfried. Ms. Hogrefe flings out a bright high-C. At that moment in time, the two singers don’t know if the production will actually happen; they are simply swept along by the irresistible glory of Wagner’s music.

~ Oberon

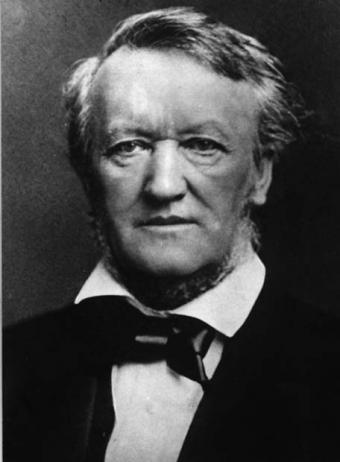

May 22nd, 2018, marked the 205th birthday of Richard Wagner. His operas remain – for me – the most absorbing in the repertoire.

Here are some highlights to celebrate his unique genius:

Anja Silja – Dich teure halle – TANNHAUSER – Cologne Radio 1968

Bernd Weikl as Amfortas – w Jan-Hendrick Rootering – Levine cond – Met bcast 1992

Gertrud Bindernagel sings Isolde’s Liebestod

Nicolai Gedda – In fernem land ~LOHENGRIN – Stockholm 1966

Wagner led a fascinating life. It is said that more books have been written about him than any other historical figure except Jesus.

May 22nd, 2018, marked the 205th birthday of Richard Wagner. His operas remain – for me – the most absorbing in the repertoire.

Here are some highlights to celebrate his unique genius:

Anja Silja – Dich teure halle – TANNHAUSER – Cologne Radio 1968

Bernd Weikl as Amfortas – w Jan-Hendrick Rootering – Levine cond – Met bcast 1992

Gertrud Bindernagel sings Isolde’s Liebestod

Nicolai Gedda – In fernem land ~LOHENGRIN – Stockholm 1966

Wagner led a fascinating life. It is said that more books have been written about him than any other historical figure except Jesus.

As Summer began to transition into Autumn, I found myself with less time for my favorite solitary pastime: listening to recordings of live performances of the operas of Richard Wagner. But I spent a long time with a 1975 Bayreuth GOTTERDAMMERUNG, re-playing certain scenes repeatedly. It’s one of the most exciting performances of that opera I’ve ever heard.

The overall majesty of this GOTTERDAMMERUNG owes a great deal to the masterful conducting of Horst Stein (above). Under his remarkable leadership, the performance drew me in from the opening chord. Not only is the great span of the work honored in all its epic magnificence, but time and again Maestro Stein illuminated what I thought were familiar passages with fresh nuances of colour or dynamic.

As the First Norn, Marga Höffgen’s voice wells up from the mysterious glow of the prelude. Höffgen (pictured above) is authoritative and she sent a shiver up my spine with the line “Die nacht weicht…” (“The night wanes…”) sung with such a prophetically gloomy resonance. Wendy Fine as the Third Norn has a strong sense of urgency in her singing, and Anna Reynolds as the Second Norn is simply superb: in voice, diction and expression she brings a thrilling dimension to this music.

Horst Stein’s spacious reading of the Dawn Music has a triumphant ring, heralding the only truly happy scene in the entire opera. Catarina Ligendza and Jean Cox as Brunnhilde and Siegfried are splendidly matched, she showing a full-bodied sense of lyricism whilst the tenor’s strong, sustained singing will be a boon to the entire performance. Stein builds the rapture of their duet exctingly, a big vocal outpouring worthy of the passions they express…passions soon doomed to betray them.

Above: Jean Cox rehearsing at Bayreuth with Wolfgang Wagner

A wonderful rocking feeling pervades Stein’s reading of the Rhne Journey; we feel like we’re in Siegfried’s boat, along for the joyride. The threesome we meet at the Gibichung Hall are as strong a trio as one could hope for: power and pride of voice from Franz Mazura (Gunther), rich lyricism from Janis Martin (Gutrune), and the start of a masterful performance of Hagen from Karl Ridderbusch.

Ms. Martin (above, with Claudio Abbado) started out singing smallish roles at The Met, eventually having a major career as a Wagnerian soprano. She was my first Sieglinde, Kundry, and Marie in WOZZECK, and she really makes her mark here as Gutrune. She, Mazura, and Ridderbusch share a strong sense of verbal detailing, keeping the dramatic situation in sizzling high-profile; Cox and Mazura are very powerful in the Blood Brotherhood scene; they sail off to the Valkyrie Rock, leaving Ridderbusch to deliver a simply magnificent rendering of Hagen’s Watch, thrillingly abetted by Maestro Stein.

Above: Anna Reynolds

The scene is now set for some truly remarkable singing in the confrontation between Brunnhilde and her sister Waltraute, played by Anna Reynolds. Ms. Reynolds is a great favorite of mine; she was my first RHEINGOLD Fricka (conducted by Herbert von Karajan at a Metropolitan Opera matinee…his only Met broadcast), and a few seasons later I had the good fortune to also experience her WALKURE Fricka. All of the things I love about Reynolds’ singing are in ample evidence in this GOTTERDAMMERUNG: her timbre is truly beautiful, her registers even; she is dynamically alert and verbally keen, a very subtle colourist with a sense of majestic authority, later overcome by despair as Brunnhilde refuses to part woth the Ring. The argument between Reynolds and Ligendza is masterfully developed by Maestro Stein, Ligendza standing her ground with firm-voiced dignity. Reynolds concludes the scene on a splendid top A-natural and rushes away.

As the flames surrounding her abode leap up. Ligendza brings great lyric joy to her anticipated reunion with Siegfried; her despair at his betrayal and her realization of his deceit are finely delineated by Stein and his orchestra; the conflict and Siegfried’s brutal seizing of the Ring are excitingly realized by the singers and conductor.

Above: Gustav Neidlinger, a fabulous Alberich

Maestro Stein commences the second act with a throbbingly sinister prelude which leads to the appearance of Alberich (Gustav Neidlinger), manifesting himself in a dream to his son Hagen. This is one of my favorite scenes in the RING Cycle, and Neidlinger and Ridderbusch give it a tremendous impact, their singing and verbal nuances meshing to great expressive effect. Neidlinger (famed for his portrayal Alberich on the classic Georg Solti commercial RING) so vividly captures the restless insistence of the dwarf, desperate of regain the ring and depending on Hagen to achieve it. Throughout the scene, the two singers receive superb support from Stein.

Janis Martin makes the absolute most of every line Wagner gives to Gutrune, and then Karl Ridderbusch unleashes a tremendous “Hoi ho!”, grandly summoning his vassals to celebrate the arrival of Gunther’s bride. The chorus’s excitement seems genuine as they sing “Gross gluck und Heil!”; of course, the festive throng soon fall into epic puzzlement as the downcast Brunnhilde appears, escorted by Gunther. Mazura’s potent singing and rugged sense of nobility will make his downfall all the more tragic. The chorus, amazed by Brunnhilde’s stupor, whisper “Was ist ehr?” (“What ails her?”); the answer comes soon enough.

Catarina Ligendza shows very slight traces of vocal fatigue in this strenuous act, but scarecly enough to be a demerit to the overall impact of her portrayal. Even when somewhat taxed, she plunges bravely onward. The swearing of the oaths – potently underscored by Stein – finds the soprano a bit stressed here and there, and Mr. Cox fudges the brief high-C. But none of this really detracts from the overall thrill of the performance. As Siegfried and Gutrune leave to prepare for the ceremony, Ligendza is back on fine form in expressing Brunnhilde’s uncomprehending woe and then her unbridled fury. Mazura limns Gunther’s shame with disturbing intensity and when Brunnhilde heaps insults in him, he is filled with self-loathing. Ligendza, Mazura, and Ridderbusch then join in the final trio which bristles with dramatic fire, fanned marvelously by Maestro Stein and the orchestra.

The excellence continues with Act III: Horst Stein’s scene-painting is colourful and detailed, and I love his trio of Rhinemaidens: they blend very well, and you can hear each voice distinctly in the harmonies. Elisabeth Volkmann (Woglinde) sings so prettily, and Inger Paustian (Wellgunde) makes a fine impression as she spies the ring on Siegfried’s finger.

I’m particularly happy to have this souvenir of Sylvia Anderson (above), a singer I heard at New York City Opera in the 1970s as Octavian and as Giovanna Seymour in ANNA BOLENA. As Flosshilde, she gives a lovely mellow depth to the Rhinemaidens’ trios; it’s really nice hearing her voice again.

Unlike some Siegfrieds, Jean Cox has plenty of voice left to spend going into Act III. He really sings: no barking or hoarseness. Calling out to the hunting party from which he has wandered, Cox produces a walloping long high-C, a note most Siegfriends can’t even hit at this point in a long evening; it’s not beautiful, but it’s such a heroic touch.

In the ensuing scene, building up to the murder of Siegfried, Ridderbush is simply superb and Mazura remarkably vivid in lines that some baritones throw away. Siegfried’s narrative has a real lilt to it, and Cox is first-rate: yest abother distinctive passage from this imperturbable performer. The orchestral playing continues to shine, movingly supporting the tenor as he regains his senses after Hagen’s spear-thrust has laid him low. This leads to a grand and glorious rendering of the Funeral March by Stein and his tireless players.

Back at the Gibichung Hall, Janis Martin is again very impressive as she awaits the return of the men. The ensuing scene, with her horror at Siegfried’s demise, Hagen’s crude cruelty, and Gunther’s shame and remorse, is filled with tremendous tension: brilliant work from Martin, Mazura and Ridderbusch, ideally underscored by the valiant Maestro.

And now it’s left to Catarina Ligendza (above) to bring this mighty performance to a close with the Immolation Scene. She summons up impressive reserves for this big sing, and although traces of strain are detectable here and there, the overall sweep of the music and the fine support she gets from Stein send her sailing forward. In the great benedictive phrase “Ruhe…ruhe du Gott!” Ligendza is splendid. She then greets Grane with a fabulous top B-flat and finishes very strongly indeed. Maestro Stein brings his masterful interpretation of this epic work to a close with stunning aural vistas of fire, flood, and redemption.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

A performance of DER FLIEGENDE HOLLANDER from Vienna 1972 piqued my curiosity, mainly because of the presence of Cornell MacNeil in the title-role. MacNeil first sang the Dutchman in a series of performamces at the Met in 1968, conducted by Berislav Klobucar. His Sentas were Leonie Rysanek, Regine Crespin, and Ludmila Dvorakova. At the time my opera-going friends and I hoped that this would mark the first of many forays into the German repertoire for the voiceful baritone: we imagined him as Kurwenal, Telramund, Wolfram, Amfortas, Hans Sachs, the Wotans, Barak, Orestes, and Jochanaan. But aside from performances as the Dutchman in Seattle in 1972 and then in Vienna in the same year, MacNeil never again sang a German role to my knowledge.

MacNeil’s a most impressive Dutchman on this Vienna issue; if his monolog lacks the palpable sense of mystery and poetic longing that the greatest interpreters bring to this music, his power is ample and his sense of vocal commitment unerring. He is well-matched in Act I by the Daland of Manfred Schenk who sings strongly; the two men’s long duet here always strikes me as Wagner at his most Verdian; their singing of it is grand yet human. Adolf Dallapozza is a clear-voiced Steersman and the chorus respond heartily to conductor Otmar Suitner’s rollicking tempo for their casting-off chorus which ends the act.

Suitner sets Act II deftly in motion with the whirring of the spinning wheels; the choral voices seem girlish.

In a marvelous bit of casting, Margarita Lilowa (above) is a full-voiced, warm-toned Mary. She brings vocal appeal to a role that is often assigned to ‘character’ singers or aging Wagneriennes.

Janis Martin (above), an American mezzo-turned-soprano, loomed large in my opera-going career. A Met Auditions winner in 1962 (she sang Dalila’s “Mon coeur s’ouvre a ta voix” at the Winners’ Concert), Martin sang nearly 150 performances at the Metropolitan Opera, commencing in 1962 as Flora Bervoix in TRAVIATA. As a young opera-lover, I heard her many times on the Texaco broadcasts. She eventually moved on to “medium-sized” roles: Siebel, Nicklausse, Lola in CAVALLERIA RUSTICANA. She left The Met in 1965 and built a career abroad, moving into soprano territory. She returned to The Met and from 1974 thru 1977; in thse seasons, she was my first in-house Kundry, Marie in WOZZECK, and Sieglinde. Another hiatus, and then she was back at Lincoln Center from 1988-1992, singing the Witch in HANSEL & GRETEL, the Dyer’s Wife in FRAU OHNE SCHATTEN, Senta, the Foreign Princess in RUSALKA, and two performances of TOSCA. An interesiting footnote from her second Met TOSCA:

“Because of an injury sustained at her previous performance of Tosca on 10/20/93, Janis Martin did not leap from the battlement at the end of the opera but committed suicide by stabbing herself with the knife she had retained after killing Scarpia in Act II."

Janis Martin sang a single WALKURE Brunnhilde at the Met in 1997, her final performance there. Elsewhere during her career she sang Ariadne, Isolde, and Ortrud.

On this Vienna HOLLANDER, Ms. Martin is thoroughly impressive. She is able to produce a clear, soft lyricism in the more refective passages of Senta’s Ballad and then cut loose with authoritative intensity at the climax.

Like Janis Martin, tenor William Cochran first came to notice as a Met Auditions winner in 1968. At the Winners’ Concert he and co-winner Jessye Norman sang the “Wintersturme” and “Du bist der lenz” from Act I of WALKURE. After singing several performances of Vogelgesang in MEISTERSINGER at The Met in 1968, Cochran went off to build his career and reputation, returning in 1984-1985 for two performances of Bacchus in ARIADNE AUF NAXOS (including a broadcast). You can hear him here in the final scene of Act I of WALKURE with Eileen Farrell. On this Vienna HOLLANDER he’s Erik, the most bel canto of the major Wagnerian tenor roles. He sings clearly and has a feel for the Italianate flow of this two arias.

The scene where Erik describes his nightmare to Senta and she becomes increasingly intense in her reactions – since his nightmare signals her dream come true – is finely played by Cochran and Ms. Martin. And suddenly the object of her obsession appears before her. Mr. Schenk sings his jovial, folkish aria very well – he has no idea where all this is leading. And then Ms. Martin and Mr. MacNeil embark on their great duet, a very taxing piece for both in terms of breath-support, a tessitura that lies high, and the need for expressiveness throughout. MacNeil has a couple off-pitch moments and the soprano is just a trifle tense (but still sucessful) on her highest notes. With Mr. Schenk they drive the trio forward, Ms. Marrtin setting the pace with her high-strung pledge of eternal devotion. There’s no break now leading into the final scene of the opera.

The boisterous chorus and booted dance-steps of Daland’s crew and their call to the Dutchman’s crew to join them are met with eerie silence at first; later when the ghostly sailors begin their hellish chant, the opposing forces mingle violently. Mr. Cochran’s sturdy singing of Erik’s plea cannot dissuade Senta and after hearing Mr. MacNeil’s farewell – laced with heartbreak – and his revelation of his true identity, Ms. Martin sails clearly thru Senta’s high-lying pledge of eternal faithfulness. Maestro Suitner curiously omits the redemption theme from the opera’s closing moments.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Sheer curiosity prompted me to order this disc of excerpts from DIE WALKURE. From the details provided, this peformance seems to have been a broadcast from the Royal Albert Hall of a concert version of the opera, with the orchestra of the Royal Opera House under the baton of Sir Georg Solti. The excerpts are rather oddly chosen: an excellent rendering of Siegmund’s Sword monolog from Act I finds tenor Ernst Kozub at his considerable best. The appetite is whetted for a continuation of the scene, but instead we jump to the final few minutes of Act I, with Claire Watson an urgent Sieglinde and Mr. Kozub ever-impressive.

Then suddenly we are in Act III, with Ms. Watson being first consoled and then inflamed by the sturdy Brunnhilde of Anita Välkki. Especially fine here are the mezzos and altos among the Valkyries as they warn Brunnhilde that her plan to aid Sieglinde’s escape may falter: Maureen Guy, Monica Sinclair, and Elizabeth Bainbridge are simply super.

The main reason to acquire this disc was to hear Forbes Robinson (above), a Covent Garden stalwart and noted Handelian, as Wotan. Back in the 1960s and 70s when I subscribed to the British magazine OPERA, Robinson’s name was everywhere. I was very curious to hear what sort of Wotan he might have been, and the answer – based on this sampling – is: marvelous! His voice is ample, rich, and warm, and he comes storming on in Act III to chastise his beloved daughter. Once the Valkyries have departed, Miss Välkki and Mr. Robinson give a truly moving performance of the opera’s great final scene, abetted with grandeur by Maestro Solti. If the soprano strays from pitch once or twice, her lovely take on Brunnhilde’s mixture of vulnerability and plucky courage is very finely expressed. The basso’s is surely one of the steadiest and most vocally pleasing Wotans I’ve ever heard, making me wish that the second act, with the god’s great monolog, had also been preserved. Robinson’s performance here amounts to a revelation, actually.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Above: conductor Eugen Jochum

And now that Autumn is slipping into Winter, I set out to select a complete live performance of TRISTAN UND ISOLDE from the several on offer at Opera Depot. I wanted to delve deeper into this opera, which over the years has somehow managed to elude my thorough devotion; my plan was to choose a recording that would hopefully inspire me, and study the score while listening.

After much weighing of pros and cons (it actually took me a couple weeks to make a final choice) I narrowed the list down to three recordings; then the Depot offered one of their 50%-off sales and I made my purchase: the performance is from the Bayreuth Festival 1953, conducted by Eugen Jochum. Within moments of putting the on the first disc, I knew I’d made a perfect choice. It’s a first-class performance in every regard, and the sound quality is very fine indeed.

Maestro Jochum is the great underlying force of this performance. From the opening measures of the prelude, with their pregnant pauses, Jochum steers a monumental course thru this score. The first voice we hear is that of a young sailor, singing from high in the rigging. The tenor is Eugene Tobin, who recently passed away. He does a beautiful job with this plaintive song: a song with a sting in its tail that rouses Isolde from her state of depressed lethargy. And we are off!

Astrid Varnay (above) is for me a very uneven singer. Aside from her recording of ELEKTRA on the Koch label, I don’t have any of her commercial recordings; but I have started to appreciate her more on these Opera Depot releases. I mulled over whether she was the Isolde I wanted to have, and indeed for the first few moments when she starts to sing, I thought that the ‘matronly’ quality I sometimes hear in her singing would be a detriment. But soon she is warmed up and she goes on to give a thrilling performance in every regard. Her lower and mid-range are on exceptional form, and the top notes trumpet out. Her dynamic control is impressive as is her shading of the text.

Ira Malaniuk (above) makes a superb impression as Brangaene, musically and textually detailed and urgently expressive. Her singing throughout Act I is compelling, and she brings a caressive softness to some passages, drawing us in.

Ramon Vinay (above) is both powerfully masculine and poetic as Tristan. As his faithful friend Kurwenal, Gustav Neidlinger barks a bit as he chides Brangaene; later he will reveal his depth of musicality and a gruff tenderness of tragic stature.

We’ve now met the main characters for Act I: Malaniuk returns from her unsuccessful errand to Tristan, and Varnay, at first subtle and then passionate, prepares to unfold her Narrative. Here the soprano is marvelous, the text vividly coloured and the singing rich and secure. Especially gorgeous is her rendering of “Er sah mir in die Augen…” as she describes the troubling glance of the wounded Tantris. Then onwards to a spear-like top B and a blazing, overwhelming curse.

Malaniuk responds with excelling lyricism and a nice, steady top G: the interchanges between her and Varnay tingle with both vocal inspiration and verbal acuity as they discuss the various potions: here Malaniuk’s singing senses the mystery and peril. It’s all thoroughly absorbing.

Varnay is imperious, grandiose as she bids Kurwenal obey his future queen and send Tristan to her at once. She then gives her orders to Brangaene, describing the potions with great intensity; their conversation again bristles with foreboding, and Varnay’s low-A at “Todestrank!” is another marvel. Maestro Jochum now draws forth the ominous build-up to the encounter between Isolde and Tristan.

This scene, which begins with a formal exchange, is perfectly underscored by Jochum’s orchestra: the buildup of tension and passion is spine-tingling, and how cunningly Varnay expresses her reasons for not having killed Tristan. As the drinking of the potion looms – with a loud interjection from the sailors – Varnay’s vocal sorcery and Vinay’s moving sense of nobility are captivating. They drink; their doom is sealed: a flood of tenderness followed by the desperate confusion of the ship’s landing and the lovers torn asunder.

As the acronical second act opens, Malaniuk’s continued perfection and Varnay’s successful lightening of the voice as they discuss Melot keep tension high. Then Brangaene/Malaniuk seeks desperately to dissuade her mistress from extinguishing the torch. Jochum’s thrilling impulsiveness as the lovers finally meet – with Varnay striking some big top-Cs – slowly settles down, and the conductor and his players steep the interlude in a misty perfume. In the love duet, the singers become poets; their urgency waxes and wanes, tenderness and rapture build and then evaporate. Malaniuk’s voice floats her warning over Jochum’s dreamy orchestra. A heroic outpouring from Varnay and Vinay…and then fate intervenes.

Ludwig Weber (above) with his huge, inky voice – full of heartbreak – is very impressive as King Marke, with a flood of painful tenderness as his narrative ends. As Tristan invites Isolde to join him in the realm of darkness, Jochum and Vinay blend is a redolent expressiveness. Then Tristan surrenders himself to Melot’s blade and in a flash, the tragedy is fulfilled.

In his doom-ladened rendering of the opening chords of Act III, Jochum again strikes at the soul. The cor anglais solo is gorgeously played. Gerhard Stolze – well-known for his Loge and Herod – shows off his lyrical aspect as the Shepherd. Gustav Neidlinger’s Kurwenal assumes epic vocal proportions here, deeply moving and drenched with humanity. And Neidlinger’s great joy as Tristan awakens is truly touching.

As madness creeps in and overtakes Tristan, Ramon Vinay veers with aching intensity from wild abandoned to fevered calm. Following a stentorian outburst, Tristan collapses; yet again Neidlinger moves us in expressing his fear that his master has died. Vinay intones a gentle “Wie, se selig”. Then the rising ecstacy as Tristan senses the approach of Isolde’s ship. The shepherd pipes up! Incredible optimism and joy: Kurwenal urges Tristan to live. But in vain: with a single rough-tender “Isolde!”, Tristan expires.

The first hints of the Liebestod are heard in the orchestra. As the steersman, a young Theo Adam (later to become an excellent Wotan and Hans Sachs), warns of the approach of another ship. Jochum now marvelously underscores Kurwenal/Neidlnger’s magnificent death. Ludwig Weber and Ira Malaniuk have their final expressions, all awash with futile despair. And then Jochum and Varnay unite for an overwhelming Liebestod.

These recordings are available from Opera Depot.

Above: Richard Wagner

Having taken a break from listening to Wagner at home while I was wrapped up with attending the RING operas at The Met, I picked up where I’d left off in playing CDs that my friend Dmitry has graciously made for me. These live recordings all come from a valuable source, Opera Depot, and this latest round of Wagnerian adventures kicks off with a 1966 performance of FLIEGENDE HOLLANDER from Covent Garden.

HOLLANDER was not the first Wagner opera I ever experienced in the theatre, but my first encounter with it (in 1968) was a memorable event with Leonie Rysanek (singing despite a high fever) magnificent as Senta, and Walter Cassel, James King and Giorgio Tozzi as the male principals.

Above: Dame Gwyneth Jones

For this 1966 performance from London, Sir Georg Solti is on the podium, stirring up a vivid performance that comes across excitingly in this recording which is in pretty good broadcast sound, with the voices prominent.

David Ward is a bass-oriented Dutchman and his singing is moving in its passion and despair, fierce in anger and with a touching human quality in the more reflective passages. He and his Senta, Dame Gwyneth Jones, manage the strenuous demands of their long duet very well: both the tessitura and the emotional weight of this duet test the greatest of singers and if there are slight signs of effort here and there in this recording, the overall effect is powerful.

Dame Gwyneth, just two years after her break-through performance at The Garden in TROVATORE casts out the powerful top notes before her final sacrificial leap thrillingly; earlier, in the Ballad she is engrossing in her use of piano singing and creates a haunting picture of the obsessed girl. The soprano’s well-known tendency to approach notes with a rather woozy attack before stabilizing the tone is sometimes in evidence; I find it endearing.

The great basso Gottlob Frick is a wonderful Daland, and tenor Vilem Pribyl holds up well in the demanding role of Erik; his third act aria – which recalls Bellini in its melodic flow – is passionately sung. Elizabeth Bainbridge and Kenneth MacDonald give sturdy performances as Mary and the Steersman.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

A WALKURE Act I from Bayreuth 1971 finds conductor Horst Stein (above) giving a great sense of urgency to the opening ‘chase’ music. Helge Brilioth, probably better known for his Tristan and Siegfried, sounds a bit rough-hewn at first as Siegmund but summons up some poetry later in the act. Dame Gwyneth Jones as Sieglinde shows both contemplative lyricism and the power of a future Brunnhilde; her singing is emotional without breaking the musical frame. Karl Ridderbusch is a darkly voluminous Hunding; despite a few moments of sharpness here and there, he makes a strong impression.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~“

The Swedish singer Berit Lindholm (above) was one of a group of sopranos – Rita Hunter, Ingrid Bjoner, Caterina Ligendza and Dame Gwyneth Jones were some of the others – who increasingly tackled the great Wagnerian roles as Birgit Nilsson’s career wound down. In 1976 Lindholm sang Brunnhilde in a performance of GOTTERDAMMERUNG at Covent Garden conducted by Sir Colin Davis, and she does quite well by the role, bringing a more feminine and vulnerable quality to her interpretation than Nilsson did. Lindholm reaches a fine peak as Act I moves toward its inexorable climax with the meeting between Brunnhilde and Waltraute, followed by the false Gunther’s rape of the ring.

Interestingly, though both the recording and the Covent Garden website list Yvonne Minton as Waltraute in this performance, there is some question that she might have been replaced last-minute by Gillian Knight; in fact, some listings for this recording on other releases do show Knight singing Waltraute. A delicious mystery, since whichever mezzo it is is impressive indeed. (I’ve left an inquiry on the Opera Depot listing, perhaps someone can shed further light…)

Jean Cox certainly has an authentic Wagnerian voice though at times in Act I his singing falls a shade below pitch. The wonderful basso Bengt Rundgren sounds fine as Hagen in Act I, and his half-siblings are Siegmund Nimsgern – later a Bayreuth Wotan – as Gunther, and Hanna Lisowska as Gutrune, a role she repeated at the Met when the ‘Levine’ Cycle was filmed for posterity.

As an admirer of the Norn scene, I’m very pleased with the three women who sing this fantastic music here: Patricia Payne, Elizabeth Connell and Pauline Tinsley. Ms. Payne is steady and sure of voice and what a delight to hear a future Isolde (Ms. Connell) and Kundry (Ms. Tinsley) in these roles; Ms. Tinsley dips impressively into her chest voice at one point, an unusual and exciting effect.

Sir Colin Davis builds the great span of the prologue/Act I persuasively; a few minor orchestral blips here and there are barely worth mentioning. Once Waltraute arrives at Brunnhilde’s Rock the conductor attains a heightened level of dramatic intensity and the act ends excitingly.

Act II opens with the mysterious conversation between Alberich and his slumbering son, Hagen. Zoltán Kelemen, who was Karajan’s Alberich when the conductor inaugurated his RING Cycle at The Met (a project from which the maestro withdrew after the first two operas) makes a fine effect, and Mr. Rundgren maintains his sturdily sung Hagen throughout this act. Jean Cox is very authoritative as he declaims his oath on Hagen’s spear; any misgivings about him from Act I are swept away here. Berit Lindholm may lack the trumpeting, fearlessly sustained high notes of the more famous Nilsson, but her Brunnhilde is exciting in its own right, with her anguished cries of ‘Verrat! Verrat!’ (“Betrayed!”) a particularly strong moment.

Whether she is the Waltraute or not, Gillian Knight is definitely one of the Rhinemaidens, joined in melodious harmonies by Valerie Masterson and Eiddwen Harrhy for the opening scene of Act III. There’s some vividly silly giggling from this trio, and Ms. Masterson in particular sounds lovely – an augury of her eventual status as a fabulous Cleopatra.

Mr. Cox has impressive reserves to carry him thru Siegfried’s taxing narrative – he’s at his best here – and if Ms. Lindholm’s voice doesn’t totally dominate the Immolation Scene, she’s very persuasive in the more reflective passages of Brunnhilde’s great concluding aria. Sir Colin Davis had built the opera steadily and with a sure sense of the music’s architecture; he saves a brilliant stroke for the end of the opera when he does not take the ‘traditional’ pause before the reprise of the ‘redemption thru love’ theme but instead sails forth into it with impetuous fervor.

There were times while listening to this performance when I wondered if this was a broadcast performance or was recorded in-house. The voices do not always have the prominence we associate with broadcast sound, but perhaps the micorphones were oddly placed. At any rate, GOTTERDAMMERUNG has again made its mark as the culmination of the great drama of The RING.

Click on the image to enlarge.

Late in the evening of February 12, 1883, Richard Wagner sat down at his piano in the Palazzo Vendramin, Venice, and played the Rhinemaidens’ Song from DAS RHEINGOLD. Wagner had been in poor health for weeks, and had come south with his family from Bayreuth following the 1882 festival to recuperate in the warmer climate of Italy. Cosima was with him that night as he finished the Rhinemaiden theme, and he said to her: “I am fond of them, these creatures of the deep with their longings.”

The next day, February 13th, Wagner felt unwell and decided to stay in his room; Cosima heard him talking to himself and shuffling thru his papers. She went down to luncheon with the children but suddenly the maid rushed in saying that Wagner was calling for his wife. Cosima dashed blindly from the dining room, running head-long into a doorframe which did not deter her. She reached her husband’s side just as he was collapsing of heart failure. His pocket watch fell to the floor. “My watch!” he exclaimed as the life drained out of him. For hours on end, Cosima remained in the room, cradling Wagner’s body. At last she was prevailed upon to return to reality for the sake of her children. Wagner’s coffin was transported back to Bayreuth and he was buried in the garden at Wahnfried. Cosima lived on for nearly fifty years before joining her husband in his resting place.

My friend Kokyat was recently in Venice and he very kindly stopped to photograph the Palazzo Vendramin for me. As someone with a mortal dislike of travel, I’m so grateful to have these images of one of the very few places that I would actually love to visit; Bayreuth is another fantasy destination. If only I could simply be there without having to get there.

The Palazzo Vendramin houses a Wagner museum in the rooms where the composer lived during his last weeks; the main floor of the building is given over to a casino. When Kokyat walked in, he was urged to buy chips and gamble but he declined.

Cosima Wagner kept a detailed diary throughout her marriage to the great composer. The story of his playing of the Rhinemaiden music on the evening before his death marked the journal’s last entry. Although she lived on for decades, her diary ended with her husband’s death.

All photos by Kokyat.

December 23, 2011 – Today is the birthday of Mathilde Wesendonck (above) who wrote five poems which Richard Wagner set to music in 1857-1858; the cycle became known as the Wesendonck Lieder. At the time, Wagner and his wife Minna lived together in the Asyl, a small cottage on the estate of Otto Wesendonck, Mathilde’s husband. It is unclear whether Wagner and Mathilde actually had an intimate physical relationship but the composer certainly was infatuated with her, causing his mentally unstable wife to erupt in jealous fits.

The poems themselves are wistful and dreamlike; their language reflects the emotional intensity of the Romantic style which by that time was highly developed. Wagner called two of the songs in the cycle “studies” for TRISTAN UND ISOLDE: in Träume we hear the roots of the love duet from the opera’s second act, and Im Treibhaus uses themes later developed in the prelude to Act 3. The chromatic-harmonic style of TRISTAN suffuses all five songs and creates the musical unity of the cycle.

Wagner initially wrote the songs for female voice and piano alone, but later produced a fully orchestrated version of Träume, which was performed by a chamber orchestra under Mathilde’s window on the occasion of her birthday in 1857. The orchestration of the whole cycle was later completed by Felix Mottl, the famed Wagnerian conductor.

Tiana Lemnitz sings the cycle’s opening song, Der Engel here.

“An angel came down to me

on shining wings

and bore my spirit heavenward.”