~ Author: Oberon

Sunday August 20th, 2017 matinee – Francesco Cavalli (above) wrote about 30 operas, and of them LA CALISTO has become a favorite with contemporary audiences. Premiered in 1651, the opera’s brief and richly-varied musical numbers – and its sensuous, lusty characters – seem wonderfully fresh and relevant to us today, especially in a performance such as was offered this afternoon by the enterprising dell’Arte Opera Ensemble down at the La MaMa Theater.

A brief synopsis of the opera will help sort out the twists of plot and the infatuations and motivations of the various characters:

THE PROLOGUE

Nature and Eternity celebrate those mortals who have climbed the path to immortality. Destiny insists that the name of Calisto be added to the list.

THE OPERA

A thunderbolt hurled by Giove has gone awry and decimated a portion of the valley of Arcadia. The god comes down with his sidekick Mercurio to inspect the damage They find the nymph Calisto, desperately seeking water. Giove causes a stream to gush up. He then attempts to seduce Calisto, who is a follower of Diana – the goddess of the hunt – and a staunch virgin. She rejects Giove’s advances, but later succumbs when he disguises himself as Diana. Meanwhile, the real Diana, because of her vow of chastity, cannot return the love of the handsome shepherd boy Endimione. Diana relies on the help of her attendant nymph, Linfea, who desires a husband but spurns the advances of a young satyr.

On Mount Lycaeus, Endimione sings to the moon, the symbol of Diana. As he sleeps, Diana covers him with kisses. He awakes and they sing of their love. Jove’s infidelity is discovered by his wife Juno, while Diana’s secret is found out by Pane, the god of the forest, who has long desired her. Endimione is persecuted by Pane and his satyrs.

The Furies turn Calisto into a bear at the command of the indignant Juno. Giove sadly confesses all to Calisto: she must live the rest of her life as a bear, but eventually he will raise her to the stars. Diana rescues Endmione and they agree that, while their kissing-fest was enjoyable, they will leave it at that. Giove and Mercurio celebrate Calisto’s ascension to her heavenly home in the constellation Ursa Major

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Sung in the original Italian, with English surtitles, the dell’Arte production is directed with wit and affection by Brittany Goodwin, who let the bawdiness of certain scenes play out without lapsing into vulgarity. The costumes by Claire Townsend mix modern-day wear with fantasy elements. The scenic design is by You-Shin Chen, and the atmospheric lighting by Dante Olivia Smith.

The score was played by an expert period-instrument ensemble led by Charles Weaver, with Mr. Weaver and Adam Cockerham playing lutes, violinists Dongmyung Ahn and Sarah Kenner, cellist Matt Zucker, and Jeffrey Grossman at the harpsichord. Their unfailing grace and perceptive dramatic accents brought Cavalli’s music into our time in all its glory.

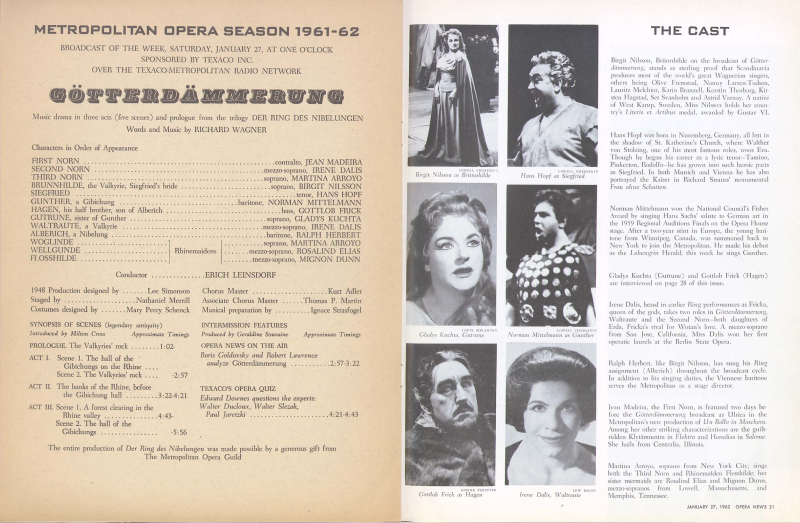

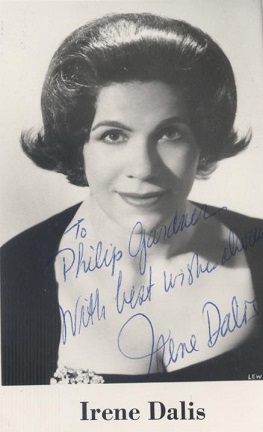

Vocally, the afternoon got off to a splendid start as Allison Gish (above, in a backstage portrait) intoned the lines of La Natura with a voice that evoked thoughts of the great contraltos of bygone days.

In a scene which anticipates Wagner’s GOTTERDAMMERUNG Norns (even down to having a contralto sing first), Ms. Gish’s La Natura is joined by Elyse Kakacek as L’Eternità and Jungje Xu as Il Destino. Ms. Kakacek looked striking as she sang from the mezzanine; the voice is full and wide-ranging, pinging out into the theater space. Jungje Xu’s voice is lyrical, and she sang very well as she pleaded Destiny’s case for giving Calisto a place in the heavens. When these three singers blended voices, the effect was superb. Later in the opera, they portrayed the stream which sprang up to quench Calisto’s thirst, and – later still – were Furies, minions of the goddess Juno, who revel in a scene where they torment Calisto.

Above: Emily Hughes as Calisto, with her fellow archers of Diana’s entourage, in a Brian Long photo. Ms. Hughes was the lovely focal-point of the story; with her clear, appealing timbre and a charming streak of vulnerability in her personification of the role, the young soprano made Jupiter’s infatuation entirely understandable. Her long aria in the opera’s second half was particularly pleasing.

Mason Jarboe as Giove (Jupiter) – handsome in appearance and authoritative of voice – was an ideal matching of singer to role. My only wish was that he’d had more to sing. The same might be said of tenor Brady DelVecchio as Mercurio; his characterful singing, easy stage demeanor, and pimp-like persona were much appreciated. Both gentlemen savoured their every moment onstage.

Above: Emily Hughes as Calisto with Adria Caffaro, who appears both as Diana and as Giove disguised as Diana. Ms. Caffaro was able to subtly differentiate vocally between her two roles; the voice is warm, sizable and pliant, with a touch of earthiness. And she exuded goddess-like confidence. After an episode of heated kissing between Calisto and Giove in his Diana guise, Ms. Caffaro returns as ‘Diana herself’ and is amused – and then annoyed – by Calisto’s description of ‘their’ smooching session and the implication that Diana might have same-sex desires: Ms. Caffaro here turned fiery, making the scene one of the highlights of the afternoon.

Above: Padraic Costello as Endimione. Mr. Costello’s honeyed counter-tenor and gift for persuasive phrasing fell graciously on the ear. His portrayal of the shepherd, infatuated with Diana, was as expressive as his singing. As the most human character in the story, and the one for whom love is truly all, Mr. Costello was as moving in his sincerity as in the beauty of sound he produced.

Above: Joyce Yin as Linfea, one of Diana’s handmaidens who is torn between preserving her chastity and losing it. Satirino, a lusty satyr, offers to solve Linfea’s dilemma for her, but she fends him off. Ms. Yin’s voice is clear and assertive, pealing forth to express her excitement. Stage-wise, she was a bundle of energy, and very amusing when she ‘remembered’ to strike the required archer’s poses.

Above: Raymond Storms as Pane. This is the opera’s second counter-tenor role and Mr. Storms excelled in the music, which veered from passionate declaration to soft, sweet turns of phrase. His acting was spot-on as yet another frustrated lover of Diana (she’s so popular!).

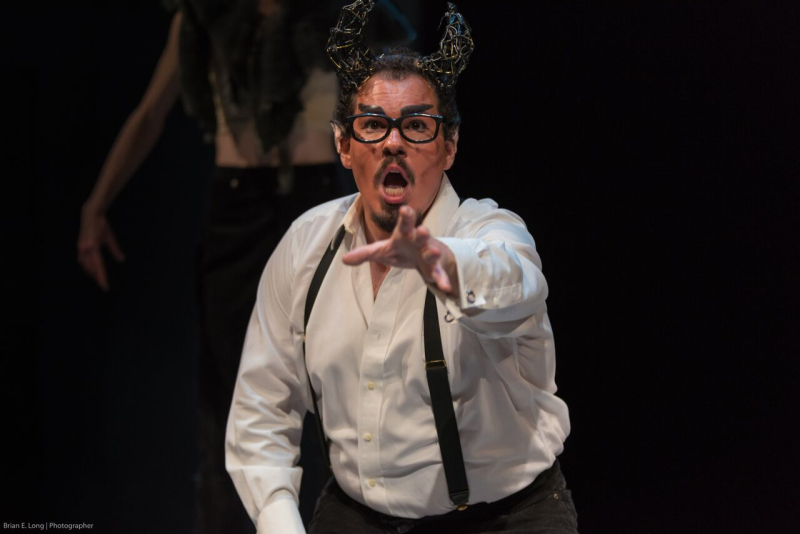

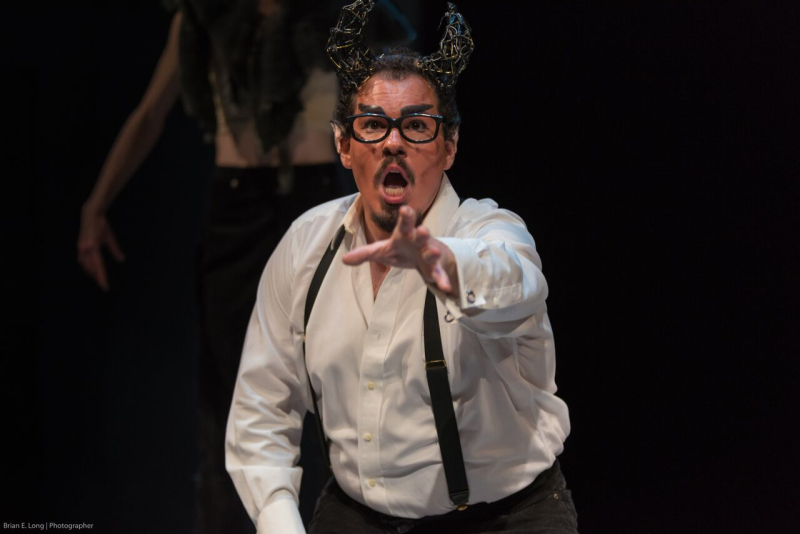

Pane’s pals are Shawn Palmer as Satirino (the satyr who tried to have his way with Linfea earlier) and Angky Budiardjono as Silvano. This trio’s scenes recall the rustics in MIDSUMMER NIGHT’S DREAM…and all three are actors who can sing.

Ms. Palmer looked androgynous with her lithe, long-legged figure and glossy blue bob-wig. Her cantering walk and occasional pawing of the ground revealed her animal nature. Her rather long dramatic aria showed a deeper side to the character, and she sang it so well.

Mr. Budiardjono’s singing was wide-ranging and ample-toned, a very pleasing sound to be sure. In Part II of the opera, Mssrs. Storms and Budiardjono have a duet that really showed off their talents; Ms. Palmer then joined them in a trio that was sheer fun to see and hear.

Sophie Delphis as the goddess Giunone, wife of Jove, did not descend from the heavens until the start of Part II. Clad in an elaborate haute couture dress, spike heels, and a flame-red hat, Ms. Delphis’ appearance was as striking as her singing and acting. A complete immersion into the character made her every note, word, and movement vivid. In a vindictive rage upon learning her husband has been unfaithful, Ms. Delphis unleashed her anger like a sylvan Santuzza. The voice has a real bite to it.

Diana’s archers also served as stagehands, quickly maneuvering floor platforms into different configurations and nimbly transforming swaths of long, hanging sheer-white fabric into clouds, canopies, or pillars.

The afternoon flew by; all too soon we were hearing what seemed to be a choral finale with all the characters mingling voices as Giove showed Calisto the firmament…her future home. But the voices fade away and the opera ends on a parlando passage from Giove.

Production photos by Brian Long.

~ Oberon

![Herbert-Ralph-02[d] Herbert-Ralph-02[d]](https://oberonsglade.blog/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/16f3be8a8b10525d86c91d3a72842754.jpg)