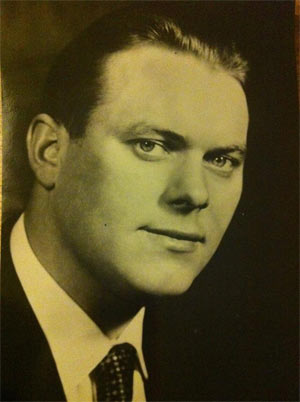

Friday October 28th, 2016 – Gianandrea Noseda (above) conducting the London Symphony at Geffen Hall, with works by Wagner and Shostakovich book-ending a performance of the Ravel G-major piano concerto by Yuja Wang. The concert was part of the Lincoln Center Great Performers series.

The evening began with the orchestra making an “entrance”. This pretentious ritual should be abandoned, and tonight’s audience weren’t buying it: there was about 5 seconds of applause and then the majority of the players had to find their places in silence. It was all mildly embarrassing. After the intermission, they tried it again and, after a smattering of hand-claps, silence again prevailed.

I’m so accustomed to hearing the overture to DIE MEISTERSINGER played from the Metropolitan Opera House’s pit that the massed sound of The London players onstage at Geffen tonight came as a jolt. To me, Gianandrea Noseda’s choice of pacing in the opening theme seemed too slow. The sound was very dense and I missed the layering of voices that can make this music so fascinating. The playing was marvelous, and the impression grandiose, but much of the time it seemed like sonic over-kill: exciting in its own way, but not finding an emotional center.

Above: Yuja Wang

I love a well-contrasted program, but following the Wagner overture with Ravel’s charmingly jazzy and often delicate G-major piano concerto – an idea that seemed ideal on paper – didn’t quite come off. The Ravel, dazzlingly played by Yuja Wang, seemed oddly inconsequential – for all its delights.

Commencing in the ‘toy piano’ register, the opening Allegramente proceeds thru varying moods – from magically mystery to bluesy languor – with the piano line woven among gentle coloristic passages from the winds and harp. In the Adagio, introspective yet subtly passionate, we’re reminded of the beautiful ‘beach’ pas de deux that Jerome Robbins created for his ballet “In G Major“. Boisterous interjections from wind instruments attempt to jar the pianist from her mission in the concluding Allegro assai, but the music rushes onward to a final exclamation point.

Yuja Wang performed the concerto superbly, making a particularly lovely impression with the extraordinary delicacy of her playing in the Adagio. In the animation of the finale, she blazed away with marvelous energy, causing the audience to explode in cheers and tumultuous applause at her final jubilant gesture. Ms. Wang is a musician who brings a rock-star’s pizazz to classical music; but far from being just a stage-crafty icon, she has the technique and artistry to stand with the best of today’s pianists.

This evening, Yuja Wang played three encores. This delighted the crowd, but in the midst of a symphonic concert, one encore suffices…or two, at a stretch; in a solo recital, you can keep encoring til the wee hours, as Marilyn Horne did at Salzburg in 1984. Ms. Wang’s third recall brought her most intriguing playing of the evening an: arrangement of Schubert’s Gretchen am Spinnrade which was hypnotic in its restlessness and its melodious mood of quiet desperation.

Is Shostakovich’s fifth symphony the greatest symphony ever written? It certainly seemed that way tonight, and though one wonders what the composer might have written had he not been in need of paying penance to Stalin following the dictator’s displeasure with LADY MACBETH OF MTSENSK, the result of Shostakovich’s desire to please under threatening circumstances resulted in this titanic masterpiece.

Maestro Noseda and The London players served up this astounding music in a performance that was thrilling from first note to last. Commencing with solo clarinet and moving on to a passage with piano and deep brass, the opening Moderato becomes extremely noisy..and then subsides. The pairing of flute and horn is a stroke of genius, with the clarinet and high violin picking up the melodic thread. The misterioso flute casts a spell.

In the Allegretto, solo winds pop up before Shostakovich commences a waltz. Irony and wit hover overall, with featured passages for a procession of instruments: violin, flute, trumpet, a bassoon duo. Plucking strings bring a fresh texture.

The dolorous opening of the Largo dispels any thoughts of lightness that the Allegretto might have stirred up. In this third movement, the brass do not play at all. Weeping strings, and the mingling of harp and flute lead to a rising sense of passion coloured by desolation. This evolves into a theme for oboe and violins. A lonely clarinet and a forlorn flute speak to us before a grand build-up commences with the strings in unison really digging into it. The music wafts into a high haze of despair, the harp trying to console. Just as the whispering final phrase was vanishing into thin air, someone’s device made an annoying intrusion: another great musical moment smudged by thoughtlessness.

The fourth movement, with its driven sense of propulsive grandeur, is thought to have marked Shostakovich’s triumph over the woes besetting him; but it has also been described as “forced rejoicing”. Whichever may be the case, the glorious horn theme, the aching strings, and the slow build-up to the epic finish certainly raised the spirits tonight. The cymbalist’s exuberant clashes at the end took on a celebratory feel.

It was reported that, at this symphony’s 1937 premiere, members of the audience began to weep openly during the Largo. Today, some 80 years on, there is still much to weep over in the world: religious and political forces continue to divide mankind; our planet is slowly being ravaged; racism, sexism, ageism, homophobia, and casual violence pervade the headlines daily. As we seem to slip deeper and deeper into some terrible abyss, it is in music, art, poetry, dance, and great literature that we may seek consolation. Tonight, the Shostakovich felt like an affirmation of faith in humanity, and we must cling to that against all odds.