~ Author: Oberon

Sunday February 26th, 2025 – A packed house at Alice Tully Hall for this evening’s concert of works by Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven presented by Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center. For me, it was a revelatory experience since I was hearing – for the first time – the Viano Quartet. Founded in 2015, the group soared to prominence after winning first prize at the 2019 Banff International String Quartet Competition.

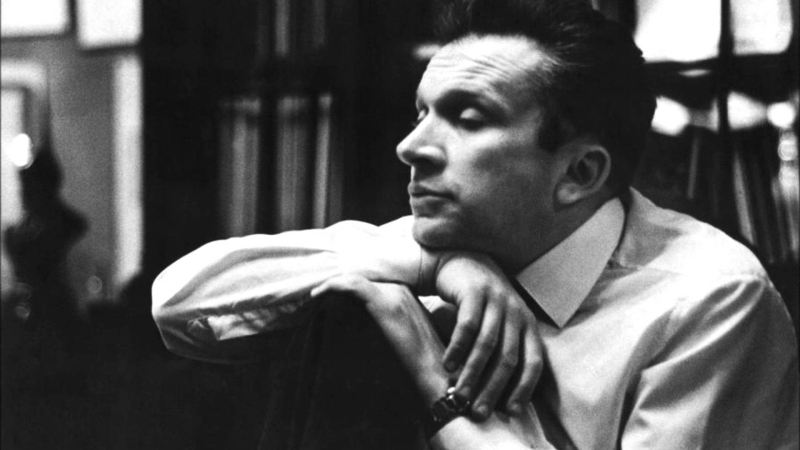

Above, the artists of the Viano Quartet: Tate Zawadiuk, Aiden Kane, Lucy Wang, and Hao Zhou. They opened this evening’s program with Haydn’s Quartet in F-major. Op. 77, No. 2, which dates from 1799. This was the last quartet the composer wrote.

The opening Allegro moderato has a gracious start; this is music that’s full of charm. It speeds up, with delightful swift passages alternating with more lyrical ones. Each voice of the Viano Quartet has its say, and each is distinctive; but the magic is in the way they are blended. An excursion into minor mode brings new emotional responses before resuming the opening mood; the movement finds a brisk finish.

The Menuetto, placed second, has a swift, witty start. Mood swings between major and minor are gorgeously negotiated by the players, whilst ironic pauses and cunning rhythmic figurations are added delights. An interlude, filled with sweet harmonies, leads on – with more clever hesitations – to a sudden finish: all so deftly played..

The Andante opens with violinist Hao Zhou and cellist Tate Zawadiuk engaged in a courtly duo; they are such wonderfully attentive and expressive artists, as pleasing to watch as to hear. The other voices join, with Mr. Zhou and Ms. Wang offering harmonized violin passages. The playing from all is detailed, but never fussy. Hao Zhou plays a decorative theme over a melodious blend from Mlles. Wang and Kane (the quartet’s excellent violist) and Mr. Zawadiuk; the latter then takes up the melody, sounding supremely lovely. Zhou then plays an exquisite ‘accompanied’ cadenza, bringing the Andante to a serene finish.

An emphatic chord kicks off the scampering Vivace assai; Zhou’s virtuosity here is so impressive, inspiring vivid animation from his colleagues. A whimsical section – like a rhythmic game – leads on to the uninhibited finale of what was destined to be Haydn’s last completed quartet. Simply terrific music-making from the Viano players, who were called back for a second bow; in the 25-minute span of the Haydn, they had soared into my upper echelon of favorite quartets.

Maintaining their high standards, the Viano Quartet then offered magnificent Mozart: the Quintet in E-flat major, K. 614, was the Master’s final chamber work, composed in April 1791, the year of his death.

Joining the quartet, one of the Society’s best-loved artists, Arnaud Sussmann, brought his viola into the scheme of things; for the program’s concluding Beethoven, he would return in his more customary role as violinist.

Mozart commences his quintet with an Allegro di molto, launched by the two violas; Mr. Sussmann and Ms. Kane immediately formed a most congenial duo, communicating artfully, and harmonizing to perfection. As this indescribably delicious movement continued, Hao Zhou displayed his silken tone and impeccable technique to striking effect.

The Andante has a prim and proper start; a theme with four variations ensues. Mr. Zawadiuk’s cello playing is particularly fine here, his tone the basis for alluring harmonies; Ms. Kane’s likewise has a special glow. The music’s enticing little pauses tempt the imagination.

The Menuetto breezes along, with repetitive descending phrases lending a playful air. A waltz-like passage ensues, with Mssrs. Sussmann and Zawadiuk setting the pace and communicating amiably.

Mozart’s finale feels like an hommage to Haydn. It has a sprightly start, and offers some perfect opportunities to savour Hao Zhou’s sweet and subtle tone. With playful pauses along the way, this Allegro leaves us pondering – as so often – what wonders Mozart might have wrought had he lived as long as Haydn did.

Following the interval, Mr. Sussmann joined cellist Paul Watkins and pianist Gilles Vonsattel for a perfect rendering of Beethoven next-to-last trio: his Opus 70, No, 2. The piece has a poignant start, with cello, violin, and piano introduced in turn. The timbres of the Sussmann violin and the Watkins cello compliment one another ideally in a duetting flow and in phrases passed back and forth. Meanwhile, from the Steinway, Mr. Vonsattel’s shimmering sounds provide a luminous contrast to the blendings of the strings. The movement has a curious finish.

With the second movement, an Allegretto, Beethoven seems to honor both Mozart and Haydn; it opens with a rather sentimental melody; then animated string passages waft over a tinkling piano accompaniment. Amusing as this was, it went on a bit longer than my interest span could sustain; yet the playing was pristine.

Another Allegretto opens with Mr. Sussmann in a violin melody played over lulling piano motifs; the Watkins cello joins the blend as sheer beauty prevails. The music gets quite quiet.

The finale gets off to a fun start with all three musicians on top form, Mr. Vonsattel especially impressive in the music Beethoven has given him; for here, after the strings have been slightly dominant in the first three movements, the piano part offers us stunning passages in which to savour the virtuosity and grandeur of the Vonsattel artistry.

As sometimes happens to me, even in the music of the greatest masters, a sense of detours and culs-de-sacs began to creep in. An ending seems to loom, only to recede as the music soldiers on.

But it was all so wonderfully played, as – in fact – was the entire program.

~ Oberon