~ Author: Oberon

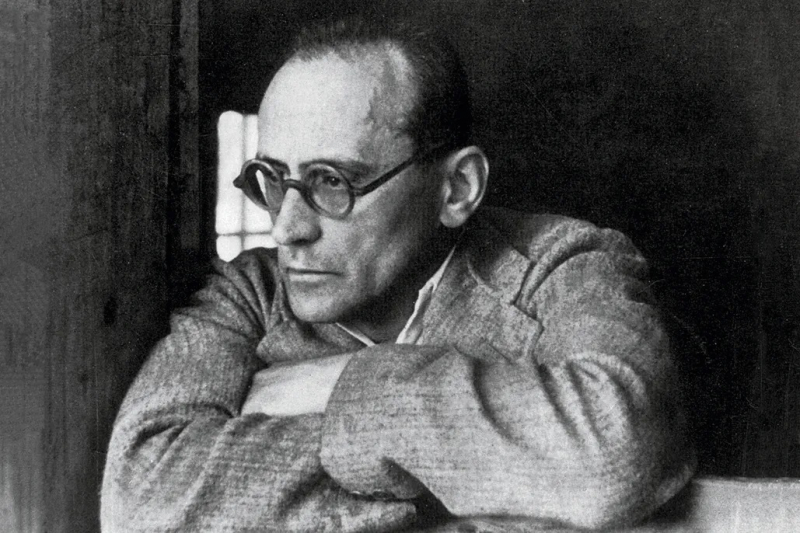

Sunday January 28th, 2024 – Pianist Wu Han and her husband, cellist David Finckel (photo above), are the co-Artistic Directors of Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center. This evening at Alice Tully Hall, they shared the stage to present a well-devised program of works by Debussy, Bruce Adolphe, Shostakovich, and Dvořák.

Claude Debussy’s Sonata for Cello and Piano, composed in 1915, was initially subtitled “Pierrot is angry at the moon“. It is a charming piece in three brief movements. The opening Prologue calls for very subtle piano playing, which Wu Han is always so good at. Skittering music is heard, followed by an awakening of tenderness. The music then goes deep. Plucking cello and staccato notes from the piano decorate the Serenade, which has a jazzy feel. For the Final, swirls of notes from the keyboard and appealing melodic fragments carry the players to a fast finish.

In 1998, Bruce Adolphe wrote Couple for Cello and Piano for Wu Han and David Finckel. The four movements suggest different aspects of an evolving relationship: the first begins dreamily, then accelerates before fading away. A warm, nostalgic feeling arises in the second movement, with the cello digging in. The slow third movement has a sentimental air, and the final section is animated and light-hearted. The composer joined the artists for a bow at the end.

Dmitri Shostakovich’s Sonata in D-minor for Cello and Piano, Op. 40 dates from 1934. A beautiful feeling of restlessness runs thru the opening Allegro moderato; the piano glitters on high, and a lovely cello theme is heard. Plucked notes and staccati spring up, and then the music slows. The following Allegro is a kind of scherzo: a swirling dance with music that slips and slides into an insistent rhythm. The songful Largo commences with a wistful cello theme that sinks to the depths; the piano sounds a steady heartbeat. The music turns dreamy, with the piano evoking feelings of peace. The cello carries us into the minor mode, seeking a quiet ending. At last we reach the final Allegro: a big, folksy dance, full of animation. There is a grand piano ‘cadenza’ which develops a sense of irony. The sprightly cello joins, and all seems well with the world. Wu Han and David Finckel basked in a sustained standing ovation, called back for a second bow as the packed hall resounded with shouts of approval.

In 1889, Antonín Dvořák wrote his Quartet in E-flat major for Piano, Violin, Viola, and Cello, Op. 87. For this finale to the evening’s program, pianist and cellist were joined by Richard Lin (violin) and Timothy Ridout (viola). These two young gentlemen looked very dapper, and they played superbly.

The opening Allegro con fuoco has an urgent start. The piano takes over, leading to an anxious passage before a joyous melody arrives. We hear colorful playing from the violin and viola as they exchange phrases or harmonize, The Finckel cello adds depth to the textures. Mr Lin’s violin sings on high, and Wu Han offers luminous piano phrases. A buzzy tremelo exchange between violin and viola is a delightful touch. Brilliant playing from all!

With a simply gorgeous cello motif, David Finckel opens the Lento, and there is magical duetting here from Mssrs. Lin and Ridout. The music turns passionate…and then charming. Achingly beautiful harmonies tug at our souls; Mr. Finckel then resumes his poignant melody, amiably supported by pizzicati from the violin and viola. There is a marvelous sheen to the sound as a progression of modulations leads us onward and Wu Han’s hypnotic playing casts a heavenly spell.

Now comes the waltz-like opening of the Allegro moderato, grazioso with its gypsy tinge. This movement contains and endless supply of marvels, including sizzling tremelos and rhythmic tapping of the strings. Melodious, dancing phrases carry us onward.

The gypsy spirit prevails into the final Allegro ma non troppo: a veritable celebration of Czech folk dance. Mssrs. Lin and Ridout were simply incredible here, for their beauty of tone and of expression. Together with Wu Han and David Finckel, they made this Dvořák masterpiece an exuberant statement about the power of music to inspire and reassure us in dark times. Tonight, these four artists gave us one of the outstanding musical experiences of recent seasons, reaffirming yet again the invaluable role Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center plays in the life of the City.

~ Oberon