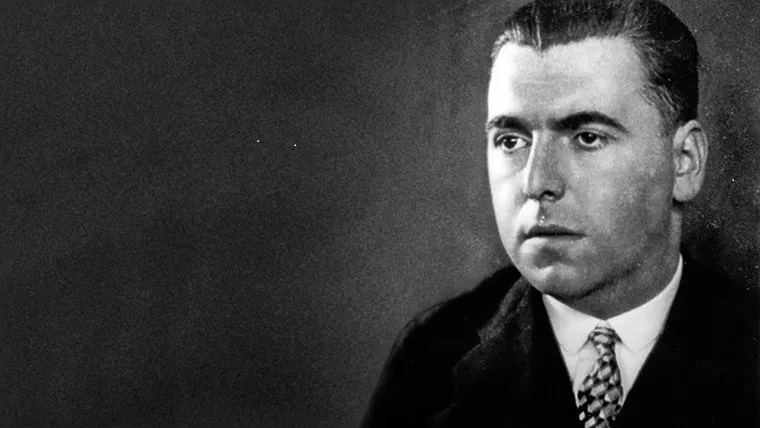

Above: cellist Michal Korman and harpist Sivan Magen

~ Author: Oberon

Thursday February 27th, 2025 – My previous encounter with the Israeli Chamber Project, in April of 2024, was nothing short of revelatory. Read about that concert here. Hoping to be similarly transported tonight, I was settling in when I realized there was no heat in the hall. It was so uncomfortable that I actually considered leaving at the intermission. Thank goodness I stayed, as the concluding Shostakovich was simply spectacular.

This evening’s program, entitled ORPHEUS’ HARP, featured four works in which the Project’s harpist, Sivan Magen, regaled us with his extraordinary artistry. Completing the program were piano trios by Shostakovich and Paul Ben-Haim.

To open the concert, Mr. Magen was joined by violinist Itamar Zorman and the lovely cellist, Michal Korman, for Orpheus, Symphonic Poem for Violin, Cello and Harp by Franz Liszt/Camille Saint-Saëns. String chords sound, soon joined by the rhapsodic harp: Mr. Magen’s playing is truly delectable, his mastery of dynamics and his agility are spellbinding. The music begins to flow, with alternating currents of major and minor. The plush blend of timbres is a balm to the ear: the unison strings are rapturous, the harp magical. Large scale tremelos from cello and violin lend a sense of drama. The cello goes deep, heralding a lamenting passage; through a series of chords, the piece reaches a pianissimo conclusion.

Jacques Ibert’s Two Interludes for Clarinet, Cello and Harp dates from 1946. Tibi Cziger’s clarinet joins Ms. Korman and Mr. Magen in the wistful opening of the Andante espressivo; the music becomes increasingly sensuous, with the dusky sound of the Korman cello wonderfully alluring. Mr. Cziger’s rich timbre, his savorable piani, and his ravishing trills are entwined with Mr. Magen’s entrancing harp passages. The second interlude, Allegro vivo, has a Spanish lilt; it is music both lively and mysterious. The cello sounds sexy, the clarinet enticing, the harp exotic; their harmonies are so evocative.

Paul Ben-Haim’s Variations on a Hebrew Melody for Piano Trio was composed in 1939. Read about the Munich-born composer here. Pianist Assaff Weisman joins Mr. Zorman and Ms. Korman in the work’s tumultuous opening; the doom-ladened cello, sizzling violin, and darkling piano create a creepy – even ominous – atmosphere. Unison, sighing strings give way to an enchanting piano solo, wherein Mr. Weisman slowly darkens the atmosphere before a rise of passion brings forth his trills and high filigree. Mr. Zorman introduces a dance filled with mood swings; the music turns waltzy. The piano sneaks up on us, suddenly sounding alarms. This is fabulous music, marked by an epic piano glissando.

The violin plays high over cello staccati, the pianist regales us with more magic before launching another dance, which comes to a dramatic halt. Mr. Weisman now introduces Ms. Korman, whose cello takes up a poignant lullaby in which Mr. Zorman joins. The music turns dreamy as this bittersweet work reaches its sublime finish.

Following the interval, Robert Schumann’s Three Fantasy Pieces, Op. 73 for Clarinet and Harp were presented by Mssrs. Cziger and Magen. In the first movement we could enjoy the clarinetist’s dulcet tone and his elegant finesse. The music is spellbinding; Mr. Magen’s playing is nothing less than sublime, and the music finds a magical finish. Fanciful harping and lyrical themes from the clarinet mesh in the second movement, which proceeds with some expert coloratura from Mr. Cziger. The third song has an exuberant start which calms to a melodic flow. An interlude veers into minor mode before we come to a swift, sweet finish. The communication between the two artists was delightful to watch from my front-row seat.

Mssrs. Magen and Weisman then took up Carlos Salzedo‘s Sonata for Harp and Piano which dates from 1922. A harpist himself, the composer ironically played the piano for the work’s premiere. The music leans towards modernism; from its fast, fun start, the piano plays a major role. A delicious sense of mystery develops, with subtle, intriguing harp motifs and trilling from both, as the instruments converse. Dynamic variety keeps the music ever-engaging; drama takes over with some extroverted keyboard passages, and then subtleties emerge. Mr. Weisman regales us with cascades of notes, and Mr. Magen has a passage with ‘prepared’ strings that alter the mood. Melismas herald an ethereal, pianissimo mood wherein a mystical atmosphere pervades. Some very delicate plucking follows; after a brief speed-up, a pacing motif leads to a dirge until some violent slashings seem to portend a dramatic finish; instead the music fades, as if it had all been a dream.

The concert ended with a thrilling rendering of Dmitri Shostakovich’s Piano Trio No. 1 in C-minor, Op. 8, played to perfection by Ms. Korman and Mssrs. Zorman and Weisman. Cast in a single movement, this music has an immediate beauty; a pensive start turns playful as the fiddle commences a dance. Order is restored, but then things again get jaunty…and briefly urgent. A charming violin passage leaves Ms. Korman to a heartfelt cello solo, with the delicate piano lending support as Mr. Zorman then takes over, his high register shining. A more animated mood evolves, and Mr. Weisman’s playing gets quite grand. Buzzing strings intrude, and some wild violin measures turn into a dialogue with cello.

There is a full stop, and then a caressive melody is passed from violin to piano before the cello joins. In cantabile mode, Mr. Zorman sounds divine…and then Ms. Korman takes up the theme, with the Weisman piano adding more colours. Lush, melodious music for the strings is embellished with shimmering sounds from the piano. Passion now rises, almost to madness; epic grandeur leads on to a swift finish.

This concert reassured me of the power of music – especially when it’s so gorgeously played – to sustain us in an increasingly dismal world. I fear so much will be lost to us in the months ahead, but music can always help us find light in the darkness. Thank you, artists of the Israeli Chamber Project, for a truly uplifting evening.

~ Oberon