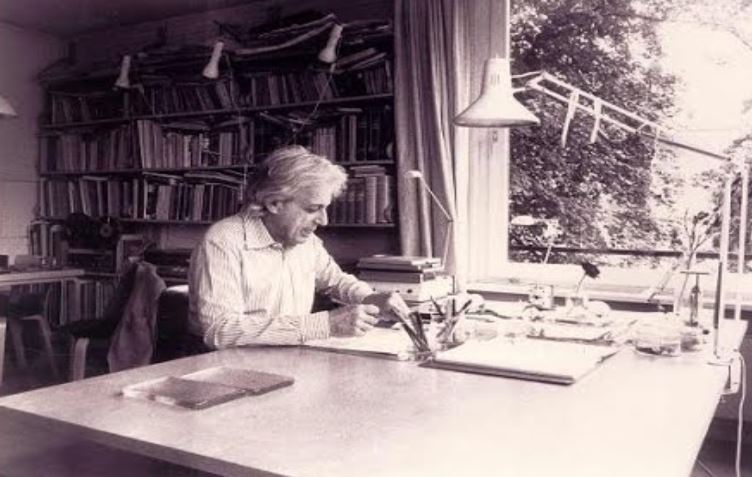

Above: Sasha Cooke in a Stephanie Girard portrait

Author: Oberon

Thursday May 25th, 2023 – Mezzo-soprano Sasha Cooke presenting a program of songs she commissioned from some of the most distinctive composers of our time in a concert at Merkin Hall. This ambitious project was conceived by Ms. Cooke in 2020, at the height of the devastation of COVID-19, and many of the songs reflect a wide range of experiences tied to the pandemic, from the virus’s global effects to intimate, domestic stories of isolation and loneliness. Pianist Kirill Kuzmin was Sasha’s perfect musical partner for the evening.

In approaching the composers and lyricists for this project, Sasha had put no limits on subject matter. Of course, the pandemic was on everyone’s mind, but other important topics were brought forward: California wildfires, school shootings, current US politics, and the internment of Asian immigrants on Angel Island in the 19th and 20th centuries.

The artists took the stage to a sustained round of applause. Sasha looked radiant in a shimmering gown, and within a few moments we were basking in the glow of her wide-ranging voice and her thoughtful way with words.

Caroline Shaw wrote both the music and the words for the evening’s title song, how do i find you. In this lyrical, melodious piece, everything that is dear to me about Sasha’s voice came into play: the warmth of her timbre, the cushioned, unforced low notes and rapturous highs, and the sheer seamlessness of it all. And she is sounding more gorgeous and expressive than ever.

A five-note descending scale is a recurring motif in Ms. Shaw’s song, tailored so perfectly to the words. The music gets quite grand, and then briefly declamatory, before a final passage of sustained tones.

Listen (music by Kamala Sankaram, words by Mark Campbell) features some lovely writing for the piano, and explores a wide tonal range for the voice. There comes a great outpouring, and then a mix of pastel colors at the end. The poet’s words are simple yet infinitely moving: “Listen, as you would to the words of a dying friend…”

Risk Not One (music by Matt Boehler, words by Todd Boss) Sasha jumps right in, and a rhythm develops; The words are urgent: “Go for broke!” Sasha’s voice is big and rich here, and Kirill at the piano has lots of lively notes to play. Glorious singing, with a big finish.

Self-Portrait with Dishevelled Hair (music by Missy Mazzoli, words by Royce Vavrek) Inspired by Rembrant’s painting of the same name, and by the idea that a self-portrait captures a moment in time, the music veers from pensive to animated to moving. “I will paint you a self-portrait of me…so that you and I, separated by centuries, might lock into each other’s gaze.”

Spider (music by John Glover, words by Kelley Rourke) was one of my favorite songs on the program, though – to be honest – all the songs were favorites. The piano begins to ripple as the spider builds her web, and the music is thoughtful. Sasha’s voicing of the words is so clear…and then she begins to hum, like a lullaby.

MasksUsedToBeFun (music by Frances Pollock, words by Emily Roller) was the most political song of the evening. It’s a light-hearted take on serious matters. From a bright start, the words are sometimes sung and sometimes spoken. Full of irony – and finger snapping – the piece rushes along, eventually taking singer and pianist to the brink of madness. The final lines are a hymn to our beloved democracy, followed by a touching piano postlude.

(During a Q & A after the performance, a woman in the audience asked why “we” (left wingers) don’t reach out to “them” (the right wingers). The answer is simple: “they” are inflexible, cannot be reasoned with, nor think of anything other than imposing their beliefs on everyone else, and getting their own way – by hook or by crook. That’s why “we” end up “talking to ourselves”, as the woman so blithely put it.)

Everything Will Be Okay (music by Christopher Cerrone, words by John K. Samson) was another favorite of mine; it tells of the recovery of a lost ‘treasure’. The song grows from a low start via simple voice and piano lines to a more dramatic passage before finding a tranquil ending, as peace of mind is restored.

After the Fires (music by Lembit Beecher, words by Liza Balkan) is a poetic narrative recalling the California fires of 2020, wherein the writer tells of returning home after the devastation. “There’s a feeling of memories having been erased along with the place.” The music covers a wide dynamic range, and the role of the piano is key. The song becomes very reflective, and finishes with a sense of quiet resignation. I loved watching Sasha sing this piece.

(A Bad Case of) Kids (music by Andrew Marshall, lyrics by Todd Boss) is a drunken song, and Sasha’s take on it made me think of Flicka von Stade’s hilarious PERICHOLE aria. A poor bloke is stuck at home with the kids all day, day after day. He pleads: “Find me a bed on the topmost floor, far from the cries of the maternity ward!” Sasha and Kirill had a blast with this song, which is quite operatic at times. The music rolls along, like something out of a music hall revue: a vivid finale to the concert’s first half.

The Work of Angels (music by Huang Ruo, words by David Henry Hwang), which tells of Angel Island and the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, where Asian immigrants were held, some for months…or even years. Of course this made me think of my beloved Wei, and the ongoing threats to Asians in this country. The singing is intimate, contrasting with some grand passages for the piano. The sound of the words becomes hesitant, as if afraid to speak of the things that happened to these people. It was some of the most poignant music we heard tonight, and it ends with a wordless vocalise.

Altitude (music by Timo Andres, words by Lola Ridge), an enigmatic and strangely captivating song, in which Sasha almost compulsively repeats words whilst Kirill plays dotty accents. Then Sasha concludes this unique song in a gorgeous high phrase.

Still Waiting (music by Joel Thompson, words by Gene Scheer) is the harrowing tale of a mother in this age of school shootings. Reassuring at first, humming to herself, the woman misses a text from her daughter telling of a shooter in the school, followed by a second text: “”I’m OK, We’re evacuating. I love you.” This brings a huge outpouring of voice. In the final unaccompanied passage, Sasha almost lost control. I imagine this song is very difficult for a mother to sing, but it needs to be heard.

In the Q & A at the program’s end, Sasha spoke of her difficulty in deciding what should follow Still Waiting. She chose That Night (music by Hilary Purrington, words by Mark Campbell), a long and rambling paean to the vitality and chaos of New York City life. It was a lot of fun to watch Sasha toss off the words; despite all the extroversion, the song has a thoughtful finish.

Inward Things is Nico Muhly’s setting of a text by the 17th century English poet and theologian, Thomas Traherne. Muhly fashioned the piece so compellingly, and Sasha brought opulent tone and an engaging dynamic palette to bear on this beauteous music. The song’s end was especially sublime.

Dear Colleagues (music by Rene Orth, words by Colleen Murphy) details the abundant problems masses of people faced during the pandemic while trying to work from home where kids, pets, and daily domestic stuff keep interrupting. The song is a working mother’s melodrama, which Sasha sang and acted with flair, whilst Kirill relished the choice piano interjections. The song has a hilarious ending.

The Hazelnut Tree (words and music by Gabriel Kahane) tells of emerging from the confines of the indoors, of newspapers and television screens, into the natural world where we can find the true beauty of life. Mr. Kahane gives the words a fine melodic flow, which Sasha voiced so persuasively.

Where Once We Sang (music by Jimmy López Bellido, words by Mark Campbell) marked the end of the evening. From the title, we knew what it would be about: lost time, lost opportunity…the pandemic months depriving musicians, dancers, and performing artists of their reason for living. Some were taken from us, others gave up. And by the time it was deemed safe again, the lost days were irretrievable.

From the song’s unaccompanied start, Sasha conveyed everything those of us for whom music is our lifeblood felt and feared throughout those dark days. The song grows in fervor, which is then becalmed, and a sense of hope and quiet rapture settles over us.

What I will always remember about this evening is the great pleasure of having been in that space with that voice.

~ Oberon