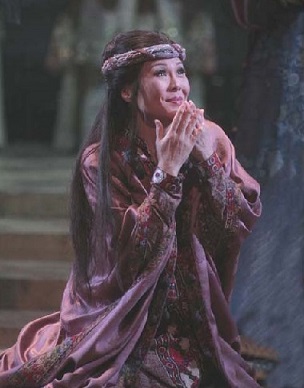

Above: pianist Benjamin Grosvenor

Author: Ben Weaver

Thursday November 17th, 2022 – The Orchestra of St. Luke’s and conductor Harry Bicket continued their multi-season traversal of the works of Felix Mendelssohn on Thursday evening at Carnegie Hall.

British pianist Benjamin Grosvenor was the soloist in Mendelssohn’s Piano Concerto No. 1 in G-minor, Op. 25, composed in 1831. The 22-year-old composer’s Piano Concerto is not a standard piece in the concerto repertoire and that’s rather inexplicable. It’s a well-crafted work, with wonderful melodies, wide range of moods, and plenty for a soloist to dig into. A stormy opening from the orchestra and a quick, dramatic entry for the soloist set the tone for a wild ride. Grosvenor is an accomplished pianist and his dazzling playing was never lacking in beauty and excitement. The concerto is written without a pause between movements, effortlessly flowing from the tumultuous first to the lyrical second movement. One thing that stands out is the lack of sentimentality from Mendelssohn: he is earnest without cheap effects, and Grosvenor reflected that wonderfully. An especially lovely passage in the Andante movement passes the melody from the piano to lower strings, and here Grosvenor and the string players of the orchestra were spellbinding. A seamless transition into a quirky final movement was nicely handled, and Grosvenor continued his dazzling playing. Perhaps only a bit of humor was lacking in the whole proceeding, but I’ll place the blame for his on Maestro Bicket because this also marred an otherwise wonderful performance of Mendelssohn’s most famous work, incidental music to A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

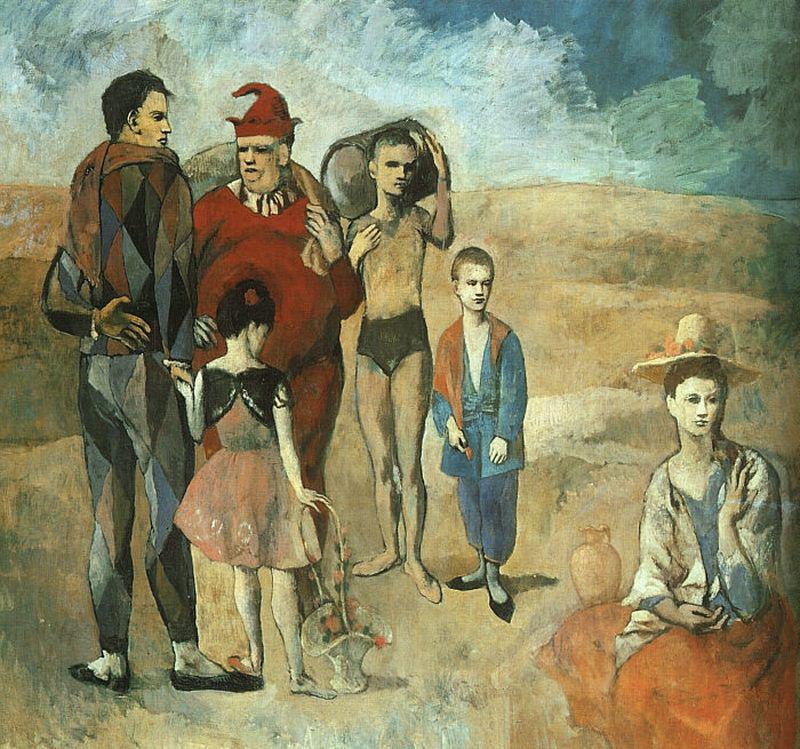

Mendelssohn composed the famous Concert Overture when he was 18 years old and it became a staple of the concert repertoire quickly: a magnificent work filled with whimsy, drama, and endlessly hummable tunes, it conquered the world. 15 years later Mendelssohn was commissioned to write additional music for Shakespeare’s play and – remarkably – the now mature composer managed to time-travel to his youth and compose a score as magical as the Overture had been. After a shimmering playing of the Overture, Bicket and the Orchestra of St. Luke’s launched into the Scherzo – a lively wind section driven ode to fairies (excellent playing by the flutes especially).

Hiding among the players all along was actor David Hyde Pierce, appearing seemingly from nowhere as Puck: which is, obviously, the best way for Puck to appear. Hyde Pierce’s performance of selected sections of the text were delightful: by turns dramatic (Titania shocked to discover her husband’s tricks), a wryly delightful Puck, and gravely pompous Oberon, the real ass of the play. The veteran actor and comedian of TV, film, and stage, moved effortlessly from one mood to the next, sometimes without taking a breath. A marvelous performance! I have always enjoyed Mendelssohn’s music for these melodramas in the work, and so many recordings omit them, alas. So it was a pleasure to hear this music, especially as sensitively played as it was.

Soprano Elena Villalón and mezzo-soprano Cecelia Hall were most excellent Fairies, one wishes Mendelssohn had written more music for the singers. Members of the The Choir of the Trinity Wall Street were also excellent in their music; I especially appreciated their very clear diction.

The Orchestra of St. Luke’s played extremely well all night. The only difficulties came in the beautiful Notturno. Featuring extensive writing for the horns, perhaps the players got tired. The only thing missing in the whole – as I mentioned above – was a sense of humor in the proceedings. The dramatic and lyrical passages were magnificent, but a somewhat lighter touch would have been welcome. Since this afflicted both the Piano Concerto and A Midsummer Night’s Dream, I’ll place this squarely on the shoulders of Maestro Bicket. Maybe he was just having one of those days; let’s blame it on a spell.

~ Ben Weaver