Above: pianist Till Fellner, photo by Jean-Baptiste Millot

~ Author: Ben Weaver

Sunday May 19th, 2019 matinee – Great Performers at Lincoln Center presenting Maestro Manfred Honeck and his Pittsburg Symphony Orchestra in a super-sized concert at Lincoln Center this afternoon: Mahler’s Symphony No. 5 was preceded by Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 5 – two substantial works that rarely share the stage.

Austrian pianist Till Fellner was the soloist for Beethoven’s 1809 magnum opus, the imposing “Emperor” Piano Concerto. By 1809 Beethoven’s hearing was already deteriorated enough that he stopped playing the piano in public. It is the only one of is concertos that he did not premiere himself. After a single chord from the orchestra, the piano enters majestically with an extended solo. This is followed by another single chord from the orchestra and a cadenza-like solo from the piano; and then again – for the third time – before the orchestra finally launches a traditional introduction.

The lovely Adagio is scored sparingly for the piano, muted strings and winds and it leads without a pause into the raucous final Rondo. Mr. Fellner is a magician behind the keyboard. There is an extraordinary sense of simplicity and ease in his playing; even in the most arduous passages, he makes the music sound like it is being played by the gods themselves. But there is nothing simple about his interpretations, which are filled with shadows and light. He makes the music come alive in a way no other living pianist does. Fellner seems to breathe the music into existence. Each live performance I have attended by this extraordinary musician leaves me in awe. Maestro Honeck and the Pittsburg Symphony musicians seemed to be breathing the same music as Mr. Fellner. They were the perfect partners for this exceptional performance.

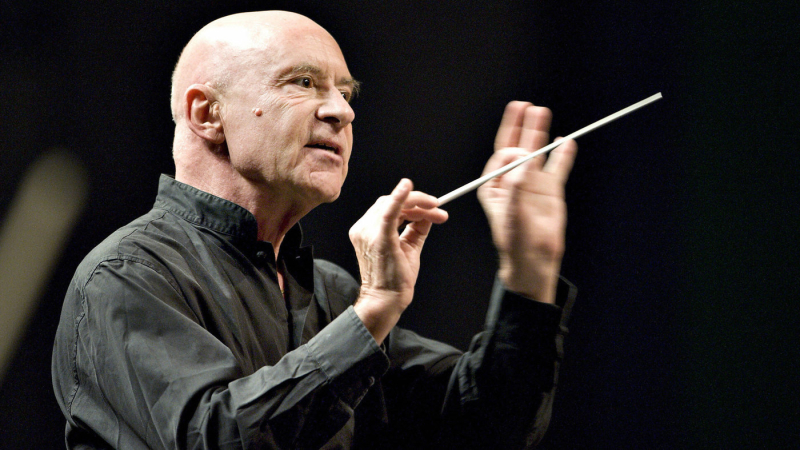

Above: Maestro Honeck, photographed by Reinhold Möller

Gustav Mahler’s mighty Symphony No. 5 received a somewhat mixed performance after the intermission. The star-turn trumpet introduction to the symphony was beautifully done, and Honeck’s tightly-controlled and dark funeral march signaled a great start. And for the Pittsburg Symphony, even at maximum volume, the sound remained wonderfully transparent. What was missing from the 3rd and 4th movements as the symphony shifts from darkness to light with its swirling waltzes, gallops and love songs (the Adagietto was nicely paced, but the climax never materialized) was a sense of fun; everyone still seemed to be stuck in the death-haunted first two movements of the symphony. Fortunately the final Rondo came whizzing in like a Mendelssohnian fairy. Honeck’s lightening of textures was a striking effect here and it brought the work to an appropriately affirming conclusion.

~ Ben Weaver