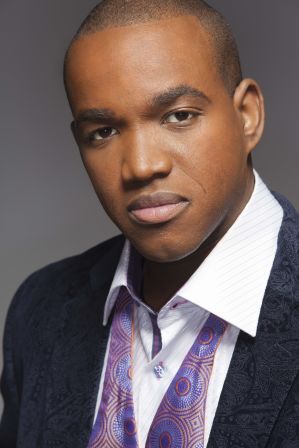

Above: Maestro Andris Nelsons; photo by Fadi Kheir

Author: Ben Weaver

Tuesday April 25th, 2023 – The Boston Symphony Orchestra, under the baton of their music director Andris Nelsons, returned to Carnegie Hall last week. The concert of April 25th, 2023 was a marvelous evening of music by Mozart, Adès, and Sibelius, featuring two outstanding soloist artists.

The great Anne-Sophie Mutter (above, photo by Fadi Kheir) performed two works: Mozart’s Violin Concerto No. 1 in B-flat major, KV 207 and the New York premiere of Thomas Adès’ Air (Homage to Sibelius) for Violin and Orchestra.

Mozart’s violin concertos have been part of Mutter’s repertoire for her entire career; it’s music she has played and internalized, and performances she has perfected, through the years. The magical performance on Tuesday night of the 1st Concerto, composed in 1773, was essentially perfect. Mutter’s golden, rich, steady tone never wavered; the soulfulness of her playing made the audience lean in. Mozart’s virtuosic writing gave Mutter no difficulties; she dispatched every run, double stop, and trill with absolute ease.

The new composition by Adès, Air (Homage to Sibelius), is a very different work from Mozart. Composed for Ms. Mutter in 2022, it’s a single-movement, semi-minimalist work (running about 13 mins) that lets the soloist stay in the upper reaches of the instrument for almost its entire run time. While the soloist played a canon – Ms. Mutter’s perfect control and steadiness were wondrous to hear – the orchestra shifted the landscape through orchestration and rhythms. Maestro Nelsons shepherded the forces around Ms. Mutter beautifully, the BSO letting the music ebb and flow. While Mr. Adès explicitly says Air is an homage to Sibelius, I heard more Arvo Pärt and John Adams than Sibelius.

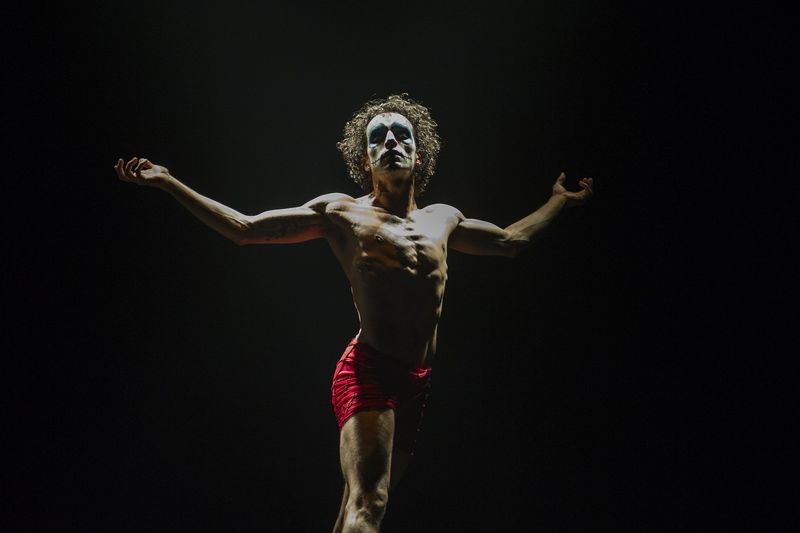

Above: soprano Golda Schultz sings Sibelius; photo by Fad Kheir

Two works by Sibelius book-ended the evening’s program. The vocal tone poem Luonnotar, Op. 70, is one of Sibelius’ most mystical and magical works. With text taken from the first “song” of the Finnish epic national poem Kalevala (a work that inspired several other major works from Sibelius), it tells the story of the (non-religious) Creation. The huge leaps and range of the vocal writing makes Luonnotar one of the most demanding works for a soprano, and South African soprano Golda Schultz was mesmerizing. Her rich voice is even throughout the range, even in the uppermost reaches it remains creamy and ravishing. Her breath control ensured she never ran out of air for Sibelius’ long and achingly beautiful melodies. Maestro Nelsons was sensitive to never let the orchestra drown out the singer. This is a work I wish would be performed more often.

Above: Maestro Nelsons and the BSO; photo by Fadi Kheir

The concert ended with an expansive performance of Sibelius’ Symphony No. 5 in E-flat major, Op. 82. Sibelius’ sound-world is really like no other. I don’t think there is another composer who composed music of such surging coldness and brilliant light. You can feel the winds sweeping across the snow and the icy water glistening in the Sun. The episodic nature of Sibelius’ writing, in the hands of lesser conductors, can be difficult to stitch together. Maestro Nelsons managed it beautifully, and the Boston Symphony – which has a long history of playing Sibelius – responded to every nuance. The orchestra’s marvelous brass section deserves special recognition here because the very exposed writing for the horns in the first and third movements was played perfectly by the ensemble. The final movement, one of Sibelius’ most famous compositions, with the majestic tolling of the horns and sweeping melody from the strings, is one of those rare truly breathtaking glories of music. It’s interesting that this overwhelming section – supposedly inspired by a flock of swans he watched passing overhead – is only played in all its Romantic glory once. When it is repeated in the second half of the movement, it changes to a darker, almost sinister tone. And the work ends with 4 chords and 2 unisons – broken by pauses. A stark and startling conclusion.

The Boston Symphony is second to none playing Sibelius; years ago Sir Colin Davis – one of the great exponents of the Finnish bard’s music – played and recorded his works with the BSO extensively. Andris Nelsons doesn’t miss a beat.

Performance photos by Fadi Kheir, courtesy of Carnegie Hall

~ Ben Weaver