Above: the Valkyries on the field of battle in the Teatro Colón’s abbreviated RING Cycle; Maestro Roberto Paternostro is on the podium

~ Author: Oberon

In 2012, the Teatro Colón in Buenos Aires presented the first performances of Cord Garben’s reduction of Richard Wagner’s monumental RING DES NIBELUNGEN; Garben cut the usual run-time of the complete Cycle from fifteen to seven hours, and meant his version to be performed in a single day. I’ve been watching it on DVD, finding it by turns intriguing and maddening.

The production was to have been directed by Katharina Wagner, great-grand-daughter of the composer. In the documentary film that is part of the boxed DVD set, Ms. Wagner arrives at Buenos Aires to start rehearsals and finds that the theatre is behind schedule in the creating of the physical production: sets, costumes, and wigs are not ready. Ms. Wagner decides she cannot work under such conditions. She flies back to Germany, but then returns to Buenos Aires…only to resign from the production.

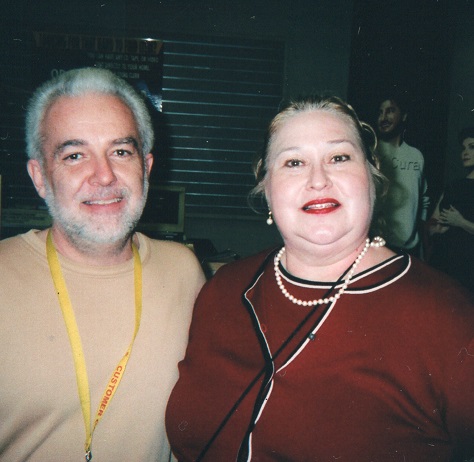

Enter one of La Fura dels Baus’s director/choreographers: Valentina Carrasco. Described by soprano Linda Watson, who plays Brünnhilde, as a ‘spitfire fireball’, Ms. Carrasco and her team take matters in hand and – in just over a month of rehearsals – get the Colón RING stage-worthy. Meanwhile, there have been problems on the musical end of things, too: some of the originally-cast singers have dropped out, and conductor Roberto Paternostro becomes frustrated with the musicians of the Colón orchestra; the Maestro walks out of a rehearsal, calling their playing “a farce”. Somehow it all comes together, and the production is a hit – at least musically.

Ms. Carrasco’s key idea is introduced early in Rheingold; the Rhinemaidens appear to be nannies guarding their treasure: a baby. Bad idea? I thought so at first. But then, babies represent the future…the hopes and dreams of mankind. Alberich steals the ‘golden child’, and by scene three, the Nibelheim scene, he has set up a ‘baby factory’ to increase his ‘wealth’: in a combination torture chamber and nursery, women are continuously and forcibly impregnated, their babies cruelly snatched from them and kept under the eye of sinister nurses. Other pregnant women are seized on the streest and enslaved, giving the term “forced labor” a fresh meaning. It’s a hellish scene, reminding us of the horrors of THE HANDMAID’S TALE.

As the Cycle evolves, we continue to see children as pawns; separated from their parents by the State, the shadow of Trump’s Amerika looms large. And in Siegfried, Fafner keeps some kids in a cage. Talk about self-fulfilling prophecies…

But what about the story-telling? The musical flow? In Rheingold, the narrative is fairly clear, but the characters of Donner, Froh, and – unkindest cut of all – Erda are eliminated altogether. Jukka Rasilainen in his military uniform with medals and gold sash, is a Perónist Wotan. And Simone Schröder, as Fricka, wears her hair in one of Eva Perón’s iconic styles. The musical cuts are scattered; in interviews, the singers speak frequently of the production’s biggest challenge: remembering what has been deleted and what your next line will be.

There’s some really good, characterful singing in Rheingold: Andrew Shore brings with him a sterling reputation as Alberich on the world’s stages, and both Mr. Rasilainen and Ms. Schröder are fine. The Rhinemaidens – Silja Schindler, Uta Christina Georg, and Bernadett Fodor – fare well on a tricky set that includes a water pool and a sandbox; I like Ms. Fodor’s voice especially. Wotan follows Gollum’s example: to get the ring, he bites or hacks off Andrew Shore’s finger with the ring wrapped around it.

Stefan Heibach is a lyrical Loge; he wears a fedora, raincoat, and sunglasses. Kevin Conners excels as Mime – later, in Siegfried, he will excel his own excellence. The giants are impressively sung by Daniel Sumegi (Fasolt) and Gary Jankowski (Fafner), the latter confined to a wheelchair. They are accompanied by a band of young thugs, some wearing soccer togs. I half expected to see Klaus Barbie flitting in and of the Nibelheim torture chamber.

Musically, the first act of Walküre, one of the most perfect acts in the entire operatic repertoire, is hacked apart. The arranger is especially unkind to Sieglinde, which is unfortunate as the role is very finely taken by soprano Marion Ammann. Ms. Ammann is an excellent singing-actress, gamely entering into the director’s concept of the role: she is indeed her husband’s ‘property’, for Hunding has kept her tethered to the floor on a short rope with a rough noose around her neck. She has been unable to stand erect for such a long time that, when Siegmund sets her free, she can barely walk. Ms. Ammann’s vocalism makes the substantial cuts in ‘Der Männer Sippe’ all the sadder. Stig Andersen, remembered for his Met Siegfrieds in the year 2000, is an excellent companion to Ms. Ammann. The pulling of the sword from the tree seems like an after-thought here. Daniel Sumegi, a paunchy Hunding, wears a wife-beater t-shirt. He sounds creepy, and he plays the character as truly revolting. We feel no shred of sympathy for this Hunding.

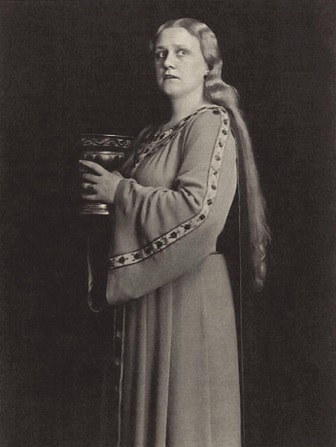

Linda Watson as Brünnhilde doesn’t sing ‘Ho-Jo-To-Ho‘ to open Act II of Walküre; Cord Garben simply jumps from Wotan’s fantastic opening lines to mid-Wotan/Fricka duet. Ms. Schröder loses a lot of Fricka’s music but does well with that which is left to her.

Mr. Rasilainen navigates the cuts in Wotan’s monologue successfully – all too soon, it’s “Das ende.” Ms. Watson’s singing of the passage where Brünnhilde weighs Wotan’s new instructions is excellent, and beautifully filmed. The pursued Wälsungs arrive, and Ms. Ammann is really thrilling in this scene of Sieglinde’s guilt and her love for her brother; her singing is expressive and passionate. Mr. Andersen is moving in Siegmund’s lines throughout Act II. The weight of the world is on him; all he wants is to be with Sieglinde. He and Ms. Watson are very effective in the Todesverkündigung (‘Annunciation of Death‘) which is staged with heartfelt simplicity. Now the cuts come fast and furious. Hunding fells Siegmund, then lets his thugs kick the hapless man to death.

As Walküre moves to its conclusion, the production becomes truly affecting. The parting of Wotan and Brünnhilde is heart-rendingly intimate and beautifully acted by Ms. Watson and Mr. Rasilainen. After Wotan has kissed away his daughter’s divinity, she sinks to the floor. White-clad angels appear and surround her slumbering form with candles – a gorgeous image:

As the Magic Fire music plays, Mr. Rasilainen as Wotan removes his military jacket and other signs of his power and command; he almost seems to age before our eyes. As the music of Walküre reaches its solemn end, he walks slowly away from the glowing Valkyrie rock: the king of the gods is now the Wanderer.

As the applause welcoming Maestro Paternostro back to the podium for Siegfried fades, someone in the audience shouts “Viva Wagner!” I was feeling about the same at this point.

This Siegfried is populated by convincing singing-actors. Cord Garben’s cuts are judicious in this opera, probably the most difficult of the four to compress. We get just enough of the Siegfried/Mime banter, with tenors Leonid Zakhozhaev and Kevin Conners very much at home as hero and dwarf respectively. Much is made of the fact that Mime is both Siegfried’s father and mother – Mr. Conners dons a blonde drag wig to accentuate his maternal characteristics. Nothung is discussed – and later re-forged – but the riddle scene for the Wanderer and Mime is completely excised.

The horn-call and solo serve as in interlude, leading us to Fafner’s cave, where Act II centers on Siegfried and Fafner. The wheelchair-bound, drowsy giant is surrounded by his entourage while his child-slaves observe the action from behind bars. There’s a rumble; Siegfried wounds Fafner. Their ensuing dialogue is excellently voiced by Mr. Zakhozhaev and by basso Fernando Rado, who is credited as the Siegfried Fafner, even thought the fellow in the wheelchair looks a lot like Gary Jankowski, who sang the role in Rheingold.

In one of the production’s serious visual lapses, the Forest Bird appears as a furry green muppet. Silly. Wotan wanders in, aged and weary; Siegfried breaks his grandfather’s spear by hand, sending the old man on his way.

The candles are still glowing around Brünnhilde’s rock. Fortunately, the opera’s dumbest line – “Das ist kein mann!” – is cut. The ecstatic genius of Wagner at “Heil dir, sonne!” finds Linda Watson at her best; she maintains peak form as cuts carry her directly to “Ewig war ich“. Brünnhilde resists, so Mr. Zakhozhaev woos her with ardent, lyrical singing. Capitulation: “Radiant love! Laughing death!” Ms. Watson falls short of the high-C. It doesn’t matter. Together, the lovers blow out the last remaining candle. The audience bursts into massive applause.

One of my favorite RING scenes, The Norns, is cut altogether. Instead, Götterdämmerung opens with the Dawn Duet; the couple seem to be living in a balconied duplex apartment in the low-rent district. Both singers are excellent here, mining the lyricism of their vocal lines music and well-supported by Maestro Paternostro and the orchestra. Ms. Watson and Mr. Zakhozhaev have this music in their blood; the soprano creates another vocal high-point as she calls on the gods to witness her love for Siegfried.

At the Gibichung Hall, Mr. Sumegi is a chilling Hagen, and he has Gutrune (Sabine Hogrefe) and Gunther (Gerard Kim) completely under his thumb. Mr. Shore’s Alberich briefly menaces Hagen. Then Zakhozhaev/Siegfred strolls in; Sumegi/Hagen is impressive as he describes how the Tarnhelm works. Mr. Zakhozhaev sings the toast to his wife expressively, but he nearly chokes on the polluted potion. Once drugged, he kisses Gutrune passionately. Siegfried’s blood-brotherhood with Gunther is mentioned almost in passing, and the two men are off to secure Brünnhilde for Gunther as Ms. Hogrefe’s cuddly, adorable Gutrune anticipates her union with Siegfried. Mr. Sumegi’s deals darkly with Hagen’s Watch.

As the Waltraute scene is cut entirely, we remain at the Gibichung Hall; Brünnhilde, dressed in a very odd, constraining bridal gown, is led in like a dog by Gunther. The whole business of “…how did you get that ring?…” is quickly dispatched, and Brünnhilde goes wild, ripping off her wedding gown and over-turning furniture. There’s no “Oath”…just Brünnhilde, Gunther, and Hagen plotting in an exciting trio.

On a golf course, Siegfried practices his swing; no Rhinemaidens here, but some caddies instead. Jarred back to reality by another potion, Siegfried extols Brünnhilde. Hagen attacks him with a golf club. Mr. Zakhozhaev sings his tender farewell to his true wife. He dies a slow death, bleeding from the mouth. During the Funeral March, his body lies alone on the stage until at last he is borne away.

In the scene of Gutrune awaiting her groom’s return, Ms. Hogrefe is quite touching; she screams when Hagen’s deceit is revealed. Hagen bullies his siblings, finally fighting with – and killing – Gunther. Brünnhilde arrives, and explains the facts to Gutrune; the set slowly turns as Gunther is carried off.

Brünnhilde is alone with Siegfried’s body. The Immolation Scene, very effective in Ms. Watson’s interpretation, becomes an intimate rather than a public ceremony: the soprano’s singing of “Wie sonne lauter...” touched me deeply; as she sang, ‘angels’ covered Siegfried with a red shroud. A vision of Wotan appears, and he looks down on how things have played out; at “Ruhe, ruhe, du Gott!” the now-powerlessgod slowly withdraws.

The Rhinemaidens enter and receive the ring from Brünnhilde; Ms. Watson is exciting, polishing off her singing to powerful effect before joining Siegfried in his shroud. The angels re-appear with candles which they arrange around the lovers’ bodies. Now the populace fill the stage; the baby is restored to the Rhinemaidens, and all of the children who had been stolen from their parents rush on to be reunited as loving families. They stand, like humanity in all its glory, looking out into the future. It made me cry, actually, while also making me disgusted with the sadists who currently hold sway over our beloved country; may the gods deliver us from evil.

Linda Watson receives a mammoth ovation – she has won me over in the course of the presentation – and Mr.Zakhozhaev is strongly hailed, rightly so. Maestro Paternostro, all of the singers, and indeed everyone on the musical side of things are heartily cheered. The production team are booed, but – while not everything in their concept worked – they saved the day, and much of what they brought forth was thought-provoking, effective…and timely.

One of the most fun bits in the documentary about the preparation for the production is a brief scene in which soprano Sabine Hogrefe (who stepped in for Christine Goerke in a Met performance as Elektra earlier this year) and tenor Leonid Zakhozhaev are rehearsing the final passage of the duet that closes Siegfried. Ms. Hogrefe flings out a bright high-C. At that moment in time, the two singers don’t know if the production will actually happen; they are simply swept along by the irresistible glory of Wagner’s music.

~ Oberon