Above: pianist Yefim Bronfman

~ Author: Oberon

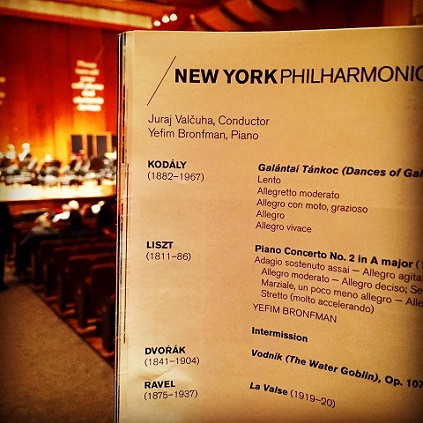

Wednesday December 27th, 2017 – My friend Dmitry and I are fans of Yefim Bronfman, so this evening’s concert by The New York Philharmonic was a perfect classical-music finale for the year 2017.

The evening opened with the overture to Smetana’s opera THE BARTERED BRIDE. I first heard this overture played live when James Levine chose it to open the Metropolitan Opera’s 100th anniversary gala in 1983. The gala (in two parts – matinee and evening) was telecast worldwide, but I was fortunate to have been in the House for the afternoon program. Let’s just say, they don’t make opera galas like that any more.

It was great fun to hear the jolly, rambunctious Smetana overture again tonight under Bramwell Tovey’s baton; the Maestro set an exhilarating, ultra-fast pace for this music, and the Philharmonic artists took up his challenge: they played brilliantly and seemed truly to be having fun into the bargain. The music passes thru many modulations along the way, and solo moments sparkle forth – notably from Sherry Sylar’s oboe – as we are danced along in a lively manner. Really, an ideal concert-opener.

Mr. Bronfman then appeared for the Bartok 2nd piano concerto. Following an ascending flourish from the Steinway, the first movement commences with rather wild brass fanfares. The piano sounds restless, set against winds; the turbulence builds only to subside, and Mr. Brofman’s playing turns subtle. Following another brass and piano build-up, there’s a full stop. Thereafter the music seems more melodious, though droll and ironic. The brass get quite noisy before the pianist silences them with a cadenza that flows up and down the keyboard. After a passage for flutes and piano, the soloist plays a double rising motif.

Pensive strings introduce the the Adagio which develops into a marvelous duet for piano and timpani. Here Mr. Bronfman and timpanist Marcus Rhoten created an incredible atmosphere: moody and a bit ominous. Suddenly things perk up without warning and we are in a scherzo-like realm with an agitato feeling and with the pianist finding unusual delicacies. Mr. Bronfman then commences a remarkable pianissimo trill that goes on and on over misterioso strings.

For the concerto’s finale, Bartók gets almost jazzy – in a slightly darkish way – and we hear from the trumpets; a feeling of a kind of war dance evolves. Another piano/percussion duet crops up – this time it’s Steinway vs bass drum – before the music turns unexpectedly dreamy. But the dream is short-lived as the trumpets re-awaken and the concerto ends brightly. Mr. Bronfman was well in his element throughout, his playing agile and multi-hued, with fine dynamic contrasts. The orchestra did their soloist proud.

By way of perfect contrast to his grand-scale playing of the Bartók, Mr. Bronfman chose for an encore Chopin’s Étude in E Major, Op.10, No.3. The opening melody of this work, thought to have been Chopin’s favorite among the études, was later the source of a vocal song arranged by the soprano Félia Litvinne and recorded famously by Litvinne’s pupil, the tragic Germaine Lubin. This evening, Mr. Bronfman’s poetic rendering of the full étude cast a thoughtful spell over the hall. This magical experience, like so many others in recent years, was sadly spoilt in its most poignant passage by the ringing of a cellphone. Yet Mr. Bronfman continued, unperturbed, and left me a beautiful memory to cherish.

Above: Bramwell Tovey

Following the interval, an exciting performance of Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exposition (in the Ravel orchestration) again found the orchestra on peak form. Opening with a brass chorale Promenade, which recurs with variations during the first seven movements, the suite conjures up visions of the works of Viktor Hartmann. Upon Hartmann’s death in 1874 at the young age of 39, an exhibition of his work was mounted at St. Petersburg. Mussorgsky visited the exhibit and was inspired by what he saw to write a set of miniatures for piano. In 1922, Maurice Ravel orchestrated the pieces.

A huge orchestra is in play, including five percussionists, two harps, and celesta. The ponderous Gnome, the child-like and playful Tuileries, the plodding Ox-Cart, the mini-scherzo of the Ballet of Unhatched Chicks, the bustling Marketplace at Limoges, the Roman Catacombs (deep brass), and the fanciful Hut of Baba-Yaga are all evoked in coloristic settings which the Philharmonic players delivered with evident affection.

The movement which most impressed me was Il Vecchio Castello (The Old Castle) in which flutes, oboe, and bassoon were joined by the mellow, distinctive voice of the alto saxophone. This music was so evocative that I got lost in it.

The suite ends on a grand note with The Great Gate of Kiev. Sumptuously played, it brought a year full of music to an imperial finish.

~ Oberon