In 1968, Lorin Maazel conducted the RING Cycle at Bayreuth and from that cycle, the WALKURE looked especially tempting to me: not only are the ever-thrilling pairing of Leonie Rysanek and James King cast as the Wälsungs and such stalwart Wagnerians as Berit Lindholm, Theo Adam and Josef Greindl featured, but a rare performance as Fricka by Janis Martin – a singer in whom I’ve recently taken a renewed interest and who in December 2014 passed away – drew me to purchase this set. It’s an exciting performance in many ways, and Ms. Martin’s Fricka is one of the best-sung I have heard.

Leonie Rysanek and James King sang Sieglinde and Siegmund together often, including on the commercial release of the entire Cycle conducted by Karl Böhm; the two singers know these roles inside-out but somehow they always manage to make the music seem fresh and genuinely exciting. Rysanek, always a powerhouse singer at The Met, scales down her voice here to suit the more intimate space of the Bayreuth Festspielhaus. She creates many poetic effects but when the emotional temperature of the drama rises, Rysanek – as ever – turns up the voltage. In Act I she produces her trademark hair-curling top notes and the famous scream (at Wieland Wagner’s bidding) as the sword is pulled from the tree.

James King is in superb voice; he sings with tireless generosity – his Sword Monolog one of the finest I’ve heard, with his astonishing cries of “Walse! Walse!” sustained with epic fervor – and he’s always vivid in the expressing the passions of the final pages of Act I. That pillar of Wagnerian basso singing, Josef Greindl, is as ever a strong and fearsome Hunding. The three singers, with vital support from Masetro Maazel (his tempos tending towards speed rather than breadth) make for a truly stimulating rendering of this act.

As Wotan, Theo Adam’s powerful voice greets his favorite daughter; Berit Lindholm is bright and true in Brunnhilde’s battle cry, and then Janis Martin as Fricka arrives to throw a monkey-wrench into her husband’s plans. Ms. Martin, at this point in her career about to transition from mezzo to soprano (in the 1970s she was to be my first in-house Sieglinde, Kundry and Marie in WOZZECK); thus the highest notes of Fricka’s music hold no terrors for her. Her singing is clean, wide-ranging, and impressive. As she and Mr. Adam debate the matters at hand, Lorin Maazel’s orchestra underscores both sides of the argument. Ms. Martin exits, secure in her triumph.

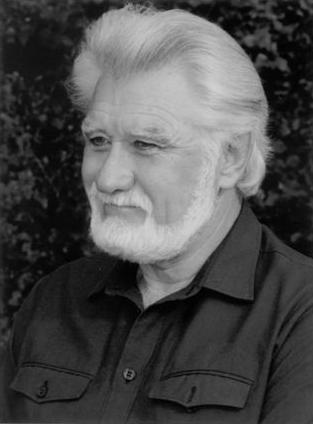

Theo Adam (above) was my very first Wotan at The Met in RHEINGOLD in 1969, and I saw him some 20 years later, still very impressive in WALKURE. His sound per se is not highly individualized – it’s basically darkish and grainy – but he always manages to use it to optimum effect. His long monolog, with keen support from Maazel and increasingly urgent responses from Lindholm, is appropriately central to the drama of the performance.

Rushing on, pursued by Hunding’s hounds, Rysanek and King make much of their scene together. For Ryssanek, moments of lyric tenderness veer off to outbursts of hysteria; King is heroically comforting. Rysanek emits a demented, curdled scream at the sound of Hunding’s approaching horns, and as she swoons, King sings “Schwester! Geliebte” as tenderly as I have ever heard it done.

In the great Todesverkundigung scene (the Annuncation of Death, where Brunnhilde appears as in a vision and warns Siegmund of his impending death in battle), Maazel brings weightiness without impeding the forward flow. A doom-ladened feeling of tension and barely controlled urgency underscores the exchange between soprano and tenor, with Ms. Lindholm expressing increasing desperation as she feels herself losing control of the situation. Maazel brilliantly emphasizes Brunnhilde’s shift of allegiance: a feeling of high drama as she rushes off.

The poignant cello ‘lullabye’ as Siegmund blesses Sieginde’s slumber is taken up by the orchestra with a rich sense of yearning, til Hunding’s horns intrude to terrifying effect. Awakening in a daze before grasping the situation, Rysanek’s mad scene reaches fever pitch. Adam thunders forth Wotan’s intercession, Rysanek screams as Siegmund is slain. After Wotan has dispatched Hunding with great contempt, Adam and Maazel rise to a thunderous finish as Wotan storms away to catch the traitorous Brunnhilde.

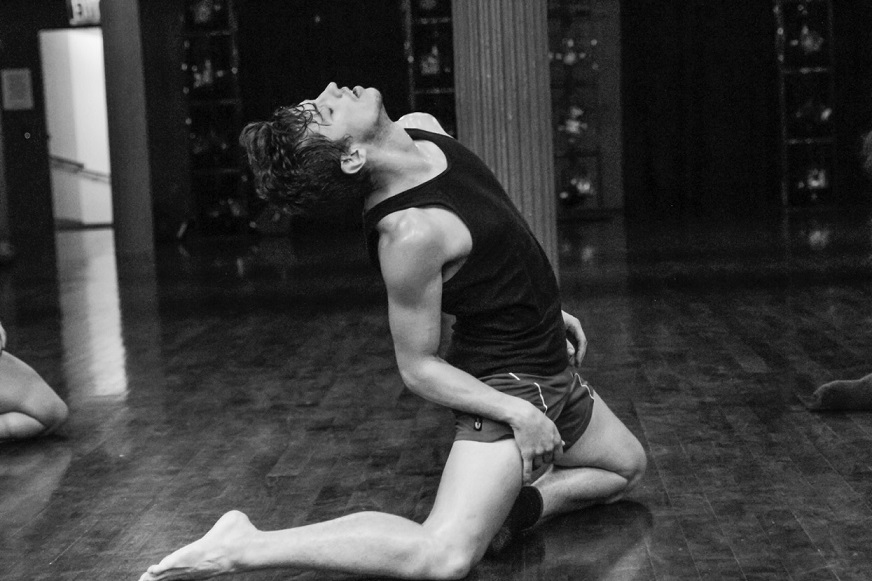

Above: Liane Synek

An excellent Helmwige from Liane Synek (sample her singing here, as Brunnhilde in a passage from a WALKURE performance in Montevideo 1959): she stands out from some rowdy singing by her sister-Valkyries.

Sieglinde’s desperate plea to be slain turns to joy as Brunnhilde informs her that she is with child, giving wing to Leonie Rysanek’s cresting ‘O hehrstes Wunder!’, the crowning moment of one of the soprano’s greatest roles.

The scene is then set for the final father-daughter encounter; both Lindholm and Adam have moments of unsteadiness and the sound-quality is sometimes marred by overload. But both singers are truly engaged in what they are singing, with Theo Adam particularly marvelous in the long Act III passage starting at “So tatest du, was so gern zu tun ich begehrt…” (“So you did what I wanted so much to do…”) Once Brunnhilde has fallen into slumber, the bass-baritone and Maestro Maazel give an emotionally vibrant performance of Wotan’s farewell.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Above: mezzo-soprano Margarita Lilowa

A RHEINGOLD from Vienna 1976 piqued my curiosity – mainly to experience the conducting of Horst Stein whose superb 1975 Bayreuth GOTTERDAMMERNG I wrote about here. I was also wanting to hear Margarita Lilowa’s Erda, having recently really enjoyed her singing as Mary in a recording of FLIEGENDE HOLLANDER, and Peter Hofmann in what is said to be his Vienna debut performance, as Loge.

The recording is clearly not from a broadcast but rather was recorded in-house; the sound varies – some overload in spots, some distancing of the voice, a couple of dropouts – and in quieter passages the breathing of the person making the recording can be heard: an unsettling effect. Also during the Alberich/Mime scene there’s some annoying mike noise. But overall, with steadfast concentration, the performance has many rewards. And chief among them is Maestro Stein’s expert shaping of the score.

The Rhinemaidens are Lotte Rysanek (Leonie’s sister, who sometimes sounds a bit like her famous sibling), Rohangiz Yachmi, and Axelle Gall. Their more attractive moments come in solo lines rather than in a vocal blend. Zoltán Kelemen, the Alberich of the era, is superb here. He paints a full vocal portrait of the dwarf, from his early semi-playful pursuit of the Rhinemaidens thru the rape of the Gold, on to the vanity of his bullying Lord of Nibelheim, his shattering fall into Loge’s trap, and the vividly expressed narrative leading up to the Curse.

Grace Hoffmann and Theo Adam are experienced Wagnerians who inhabit their roles thoroughly. The mezzo’s voice is no longer at its freshest (she was in the twenty-fifth year of her career here) but she is authoritative in characterization. Adam, strong and true of voice, makes a fine impression throughout, especially in his final hailing of Valhalla.

Hannelore Bode’s voice seems too weighty and unwieldy for Freia, but the giants who pursue her are impressive indeed: Karl Ridderbusch and Bengt Rundgren are so completely at home as Fasolt and Fafner, and their dark, ample voices fill the music richly. Hale and hearty one moment, and wonderfully subtle the next, both bassos make all their music vivid. A lyric Froh (Josef Hopferweiser) and an ample-toned Donner (Reid Bunger – his “Heda! Hedo” has a nicely sustained quality) are well-cast.

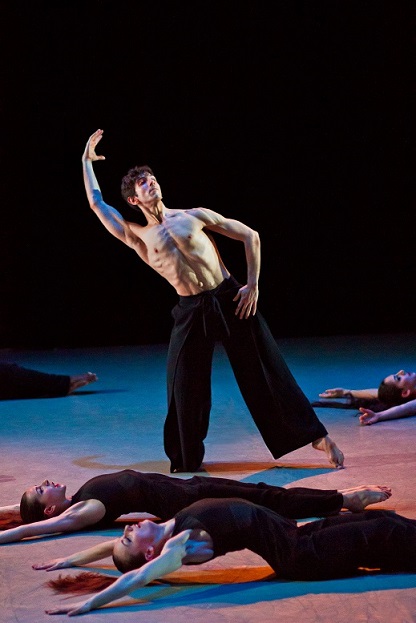

Above: tenor Peter Hofmann

Peter Hofmann’s Loge has a baritonal quality, and he blusters a bit but soon settles in to give a sturdy if not very imaginative performance of the Lord of Fire. The Nibelheim scene finds Adam, Hofmann, and Kelemen all at their keenest in sense of dramatic nuance, and Heinz Zednik is a capital Mime, well-voiced and inflecting the text with eerie colours.

Ms. Lilowa’s Erda, sounding from a distance at first, comes into focus after her first line or two and has a round-toned, steady voice, making the most of her brief but important scene.

Horst Stein’s overall vision of the score seems nearly ideal to me, and there are a number of particularly satisfying passages: his underscoring of the big lyric themes in Loge’s narrative, the detailing of the orchestral parts at Loge’s mention of Freia’s apples, the descent to Nibelheim. And once in Alberich’s domain, Stein shows keen mastery of nuance, both in colorfully supporting the dialogue and in a truly ominous “dragon” theme for Alberich’s transformation. Throughout the performance, it’s Stein who keeps us keenly focused on this marvelous score.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

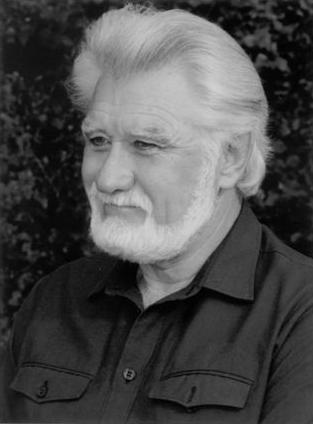

Above: Sir Donald McIntyre

Another RHEINGOLD – a recording of a performance I actually attended – is from a Met broadcast of February 15th, 1975. It’s interesting to compare my reactions to the recording with what I had written in my opera diary on the day of the performance, some forty years earlier.

The 1974-75 season was a rich one for me; I was living (though not enrolled) at Sarah Lawrence College with TJ. We’d had our summer on Cape Cod together and, as we prepared to part company and resume our separate lives, we found we’d become so attached to one another that, only a few days after I’d returned to the tiny town and he’d moved into the college dorm, we threw caution to the wind and I went down and got a temp job at IBM in Westchester County and slept with him in his twin bed (he had drawn, luckily, one of the few ‘private’ room on the entire campus). We went down to Manhattan for the opera and the ballet three or four times a week.

The Met were doing the RING Cycle that season, with Sixten Ehrling conducting. The virtues (or not) of his readings of the scores were hotly debated by the fans; he was sometimes booed when entering the pit, and sometimes cheered when he took his bows at the end of each opera. I thought at the time his conducting was “maybe lacking in grandeur, but well-paced and considerate of the singers.” Listening to it now, his RHEINGOLD seems perfectly fine, with many very satisfying passages…despite some fluffs from the horns here and there.

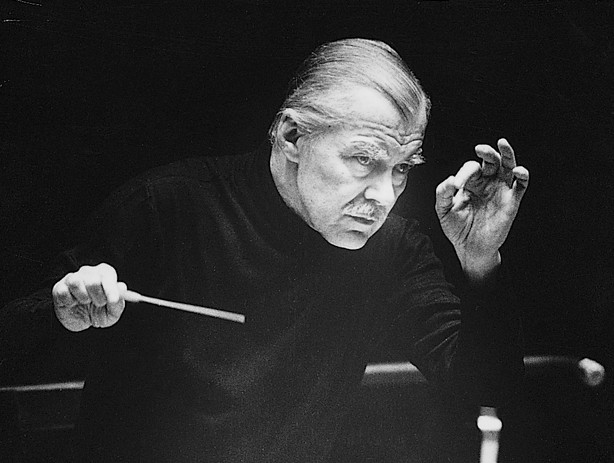

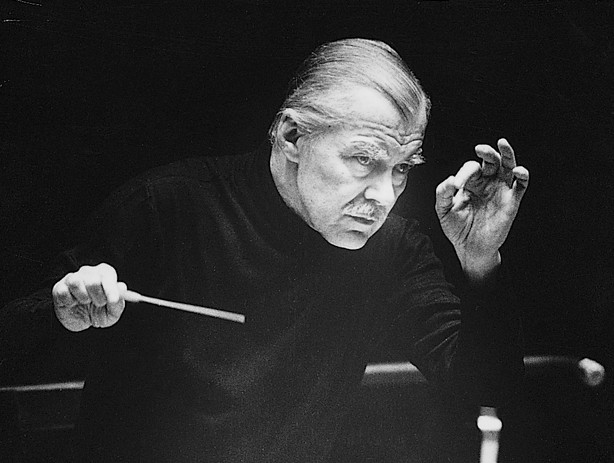

Above: Sixten Ehrling

(Note: in 1998, when I started working at Tower Records, I met Maestro Ehrling and his charming wife, a former ballerina. The first day I met him, he was in a cantankerous mood because all the clerks were busy and he was in a rush. I stepped up, greeted him with a little bow, and immediately began to talk to him about his RING Cycle. He became a regular customer and regaled me with all sorts of wonderful stories about the singers he had worked with. He also liked to correct my pronunciation; when I referred to Wotan’s daughter as “Broon-HILL-da” he yelled: “BROON-hil-d…” I ended up really enjoying our little friendship, and missed him when he became too ill to come to the store…though he’d often send his wife to us, with strict instructions as to what to buy for him. He passed away in 2005.)

Christine Weidinger, Marcia Baldwin, and – especially – Batyah Godfrey are good Rhinemaidens; they raise the performance level starting with the first appearance of the ‘gold’ motif. Marius Rintzler seems at first to be a bass-oriented Alberich (though later his topmost notes are wonderfully secure) and he becomes actually scary as his plan to steal the treasure takes over his mind. Abetted by Ehrling, the scene of the rape of the gold is dramatically vivid.

Ehrling scores again in his super-reading of the descent to Nibeheim. Rintzler as Alberich, in his own domain, lords it fabulously over his brother and his slaves. Later, betrayed, Rintzler’s performance rings true in its desperation and his powerful declaiming of the curse.

The opera’s second scene shows Ehrling at his best, with a nice sense of propulsion and excellent support of his singers. This matinee marked the Met debut of Donald McIntyre as Wotan; he would become known and beloved worldwide a few years later when the Chereau RING was filmed for international telecast at the Bayreuth Festival. On this afternoon in 1975, he makes a superb impression: he begins a bit sleepily (Fricka has just awakened him) but once he claps eyes on the finished Valhalla, his godliness rises to full stature. His singing throughout is generously sustained; by turns imperious and subtle, he makes an ever-commanding dramatic impression. McIntyre’s final scene, hailing the new home of the gods and dismissing the Rhinemaidens who plead from below for the return of the ring, is really exciting.

Mignon Dunn, always a great favorite of mine, is an immediately distinctive Fricka. The role is rather brief, but Mignon makes the most of every opportunity, and her gift for vocal seduction manifests itself near the end, as she lures Wotan’s thoughts away from the mysterious Erda and turns them instead towards Valhalla (where she hopes to keep him on a tighter tether…but, it doesn’t work.)

Glade Peterson, as Loge, seems rather declamatory at first. His ample voice serves him well in the monolog, despite some moments of errant pitch. He lacks a bit of the subtlety that can make Loge’s music so entrancing. As the hapless Mime, Ragnar Ulfung is both note-conscious and characterful; he makes a string impression though once or twice he too wanders off-pitch.

The giants are simply great: John Macurdy’s Fafner is darkly effective – he has less to sing than his brother Fasolt, but he will eventually get the upper hand…violently. Bengt Rundgren as the more tender-hearted of the two is truly authoritative, with page after page of finely inflected basso singing.

Mary Ellen Pracht, a Met stalwart, does well as Freia, and William Dooley is a splendid Donner…his dramatic, full-voiced cries of “Heda, Hedo!” are in fact a high point if the opera, and are punctuated by a fantastical thunder-blast. Tenor Kolbjørn Høiseth is rather a fuller-toned Froh than we sometimes hear; there’s something rather ‘slow’ about his delivery. (A few days later, he sang a single Loge at The Met, and then a single Siegmund.)

In the house, the amplifying of Erda’s Warning ruined the moment musically, but this does not affect the broadcast which is picked up directly from the stage mikes. And so Lili Chookasian makes an absolutely stunning effect with her rich, deep tones. Where are such voices as hers today? After “Alles was ist, endet!” and “Meide den Ring!”, one feels chills running up and down the spine. Magnificent!