Above: the Shanghai Quartet

~ Author: Oberon

Tuesday March 27th, 2018 – The last concert of Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center‘s Winter festival, entitled Chamber Music Vienna.

Ignaz Schuppenzigh (1776-1830) is credited with pioneering the ‘chamber music series’. Schuppenzigh was a violinist and a friend of Beethoven who presented over a hundred chamber music concerts in Vienna between 1823 and 1828. Works of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven were prominently featured in the programming, and it is precisely those three composers whose music we heard this evening.

But tonight’s concert had a deeper significance, for it duplicated exactly the program Schuppenzigh offered in Vienna on March 26th, 1827 – the very day that Beethoven passed away. In fact, it has been determined that the moving Largo con espressione from Beethoven’s Trio in G major, Op. 1, No, 2, was being played the exact time of the great man’s passing.

The Shanghai Quartet opened this evening’s concert with Haydn’s Quartet in G major for Strings, Hob. III:81, Op. 77, No. 1 (1799). The Shanghai have their own distinctive sound, cool and concise, suited well to both their Haydn and Mozart offerings on this program.

The opening movement of the G major quartet, marked Allegro moderato, has a feeling of perpetual motion, somewhere between a march and a dance. There are ingratiating modulations and the writing is quite florid. By contrast, the Adagio, with its unison opening, has an almost operatic feeling. Courtly, and with gracious harmonies, the first violin sings forth and then engages in a duet with the deepening cello. Rising modulations – with the cello ever-prominent – bring a da capo which, with varying harmonics, reaches an emotional level I don’t often feel in Haydn’s music. The Shanghai made much of this movement’s sheer beauty.

The Minuet has the genuine air of a scherzo; it’s fun, with swirls of notes carrying the violin on high. The swift, unison start of the Finale: Presto brings some very nimble playing from the Shanghai’s 1st violinist, Weigang Li; the music becomes genuinely exhilarating.

Next came Mozart: his Quartet in D-major for Strings, K. 575, is one of the “Prussian” quartets (dating from 1789) and as such features the cello as a nod to the cello-playing king, Friedrick Wilhelm II. In the opening Allegretto, it is the cello that presents the second theme; here, and throughout the piece, the Shanghai’s Nicholas Tzavaras shone.

While the Andante clearly showcases the cello, Mozart doesn’t shirk on opportunities for the violist – Honggang Li – or the violins, Weigang Li and Yi-Wen Jiang. Mr. Tzavaras is really in his element with the melodies, and at one point a matched phrase is passed from voice to voice. Quite inventive.

Following the light, jesting feeling of the Menuetto (Allegretto), the concluding Allegretto‘s theme takes the cello to its high register. A decorative canon pops up before we reach the finale.

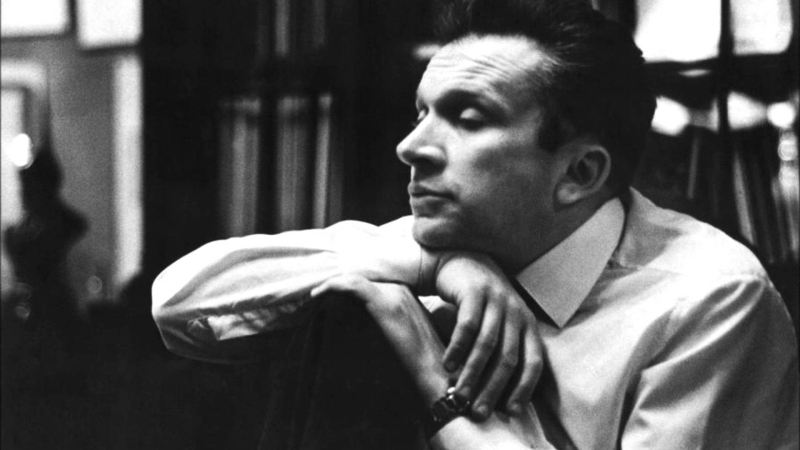

Above: Beethoven’s tomb in Vienna’s Central Cemetary

The evening ended with Beethoven’s Trio in G major for Piano, Violin, and Cello, Op. 1, No. 2. Pianist Gilbert Kalish, violinist Arnaud Sussmann, and cellist Paul Watkins took the stage for a first-rate performance of this work from a still-young composer.

Following a slow introduction, in which the lovely blend of the strings and the stylish Steinway work of Mr. Kalish heralded delights to come, the first movement goes Allegro in quite a lively, sometimes folkish manner. The writing has its witty aspects, but the two women in front of us decided they’d never heard anything so hilarious, and they struck up a running conversation, laced with chuckles. Shushing was to no avail.

Arnaud Sussmann’s absolutely gorgeous tone made a glowing impact in the Largo con espressione, inter-weaving with the bounteous beauty of Mr. Watkins’s cello to irresistible effect as refined romance bloomed from the keyboard. This Largo is considered to be Beethoven’s first great slow movement.

Following the Scherzo, which bounces from major to minor and back, light-weight agitation marks the Finale: Presto. One violin motif seems like a pre-echo from Rossini’s GUILLAUME TELL overture. With its rhythmic vitality and breezy, devil-may-care lilt, the Presto comes to a vivacious end.

~ Oberon