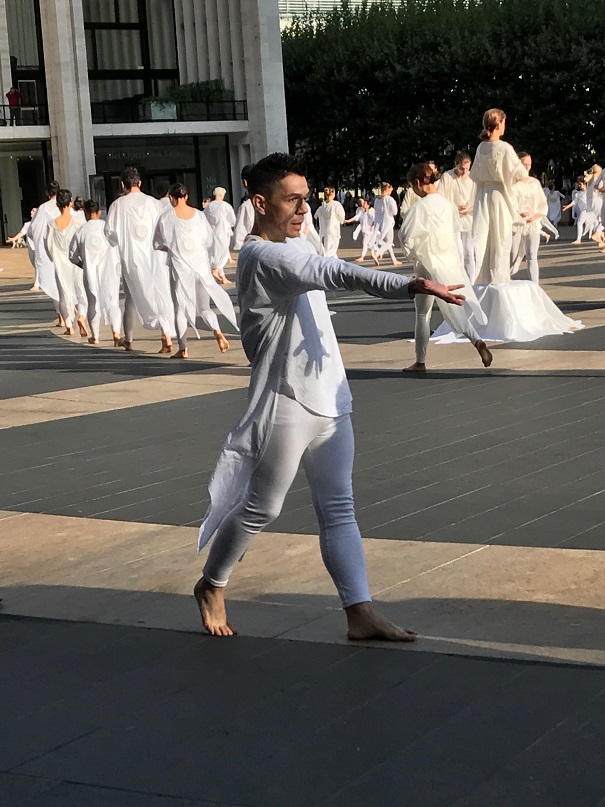

Above: The New York Philharmonic’s concertmaster Frank Huang

~ Author: Oberon

Wednesday November 22nd, 2017 – The announcement of the death of the great Russian baritone Dmitri Hvorostovsky coloured my entire day. It came, by unhappy coincidence, on the anniversary of the assassination of John F Kennedy which took place in 1963: the most disturbing world-event of my youth. That brutal murder – and its aftermath – I still remember so clearly.

This evening, I went as planned to The New York Philharmonic‘s program of Russian and French works. Though I was in the mood for darker, more soul-reaching music, the program – magnificently played – did lift my spirits, if only temporarily.

As far as I know, Mr. Hvorostovsky appeared with The New York Philharmonic for only one program: in 1998, he sang Mahler’s Kindertotenlieder with the orchestra. I was there, and was swept away by the peerless beauty of his voice and by his deeply poetic interpretation. How I wished he could have been with us again tonight. But the program did commence with music from Hvorostovsky’s homeland: a suite from Nicolai Rimsky-Korsakov’s opera The Legend of the Invisible City of Kitezh. It ended up being my best-loved work of the evening and it was brilliantly delivered by the Philharmonic players, under Gianandrea Noseda’s baton.

Hearing music from The Legend of the Invisible City of Kitezh brought back memories of a day in 1983 when I stepped off a bus in Boston on a Sunday afternoon and began walking towards the opera house where the Rimsky-Korsakov opera was being performed at a matinee. Suddenly the sky opened up; no store that was open sold umbrellas. I made a run for it, but was literally drenched from head to toe by the time I got to the theatre. Needless to say, I did not enjoy the performance at all, and left at intermission…still soaking wet.

The suite from The Legend of the Invisible City of Kitezh is in four movements, depicting episodes from the opera: a Hymn to Nature, Fevronia’s wedding procession, the invasion of the Tatars and the subsequent battle, and Fevronia’s Ascension to the Invisible. It begins on a sombre note, with harps adding a touch of magic. Throughout the suite, solo wind passages abound; Maestro Noseda brought out these colouristic facets, and the Philharmonic artists played them delightfully.

A broad viola theme stands out, and the percussionists are kept on their toes with bells, chimes,and glockenspiel in addition to the timpani, bass, and snare drums that come to attention for the battle scenes. The suite was an excellent program-opener.

It’s always a great pleasure when principals from the Philharmonic step into the concerto spotlight. Tonight, concertmaster Frank Huang performed Camille Saint-Saëns’ Violin Concerto No. 3 – my first time hearing it live. The concerto begins without an orchestral introduction; instead, only quiet, darkish chords provide a background for the rather harsh opening phrases of the violin. Mr. Huang’s playing here seemed a little unsettled, with traces of sharpness of pitch. But within seconds, the violinist had settled into the music and gave a really impressive, technically assured performance.

As the concerto’s first movement develops, there are dramatic contrasts between full-bodied, passionate themes and more sedate passages. There is a sense of yearning in the music which Mr. Huang conveyed to perfection. In the Andantino which follows, the composer meshes the solo violin with winds in music with an elegant air.

The concluding movement begins with a slow introduction and some almost jagged interjections from the violin. The Allegro non troppo itself is launched with an up-sweeping motif for the solo violin. Passages of coloratura for the soloist alternate with more lyrical elements; then commences a surprising cantabile, where Mr. Huang’s beauty of tone was ravishingly engaging. Pages of virtuosic writing show off the soloist’s fluent technique, and hints of gypsy passion are thrown in. The leaping violin theme returns and is most welcome. An orchestral chorale is an innovative detour before the concerto sails on to a bravura finish. Mr. Huang was rightly accorded a prolonged ovation from the audience whilst his onstage colleagues tapped their bows and stamped their feet in acclaim.

Above: Gianandrea Noseda

Rachmaninoff’s Symphony No. 3, under Maestro Noseda’s baton, followed the interval. Like so many symphonic works, its a piece I’m not really familiar with, and I must say, I felt slightly disappointed with it musically. It’s all terribly impressive and enjoyable to hear, but the emotions are rarely engaged. Perhaps it was just my mood, but I kept longing for a deeper experience.

That said, the artists of the Philharmonic played it most impressively. And it is to them that I owe thanks for moving or thrilling me on this evening: to Mr. Huang of course, but also to other players who had prominent passages tonight: Sheryl Staples (violin), Yoobin Son and Mindy Kaufman (flute/piccolo), Sherry Sylar (oboe), Pascual Martinez Forteza (clarinet), Kim Laskowski (bassoon), and Amy Zaloto (bass clarinet).

Encouraged by the great success of his Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini (1934), Rachmaninoff started work on his third symphony in the summer of 1935. Leopold Stokowski and the Philadelphia Orchestra gave the premiere on November 6, 1936. It was not well-received by the audience, nor by the press. Perhaps, as with those early auditors, I need to hear it a few more times to cultivate a more positive reaction.

There are countless appealing passages – a cello tutti was especially beautiful – and the final movement’s journey from optimism thru a vale of doubt and the onward via a meditative passage to a ringing conclusion evoked a big response from the Geffen Hall audience.

~ Oberon