Above: Stuart Skelton and Eva-Maria Westbroek as Siegmund and Sieglinde/a Met Opera photo

~ Author: Oberon

Saturday March 30th, 2019 matinee – I admit that I am not feeling excited about the Met’s current RING Cycle performances. Much as I have been starved for Wagner in recent Met seasons, and despite the RING being very high on my list of favorite works, a lot of the casting this time around is uninspiring. And, if the free-standing RHEINGOLD I saw recently was any indication, Philippe Jordan’s Wagner conducting doesn’t really send me. So I went to this afternoon’s WALKURE simply because it’s WALKURE.

En route to the theater, I encountered Michael Volle, the alternate Wotan, heading for the Met’s stage door in the passageway under Lincoln Center. I wondered if there would be a cast change, but – after a delayed start of fifteen minutes – the performance commenced with the announced cast.

I did not stay for the third act; after debating with myself, I decided to leave before enduring another prolonged intermission. Then on the train going home, I thought: “What if that was your last WALKURE…ever?”

Blasts of frigid air (common up in the Family Circle boxes) continued throughout the performance; whilst waiting for the House to go dark, we heard a gorgeous cacophony of Wagnerian leitmotifs from the musicians warming up.

The singers today ranged from stellar to acceptable, but Maestro Jordan seemed far more impressive here than in the RHEINGOLD, and the orchestra playing was – for the most part – thrilling, both in its overall resonance and in the many featured opportunities; the cello (especially before “Kühlende Labung gab mir der Quell“), the clarinet (as the mead is tasted, and later in the prelude to the Todesverkundigung ), the somber horns and heartbeat timpani in that magnificent Annunciation of Death…and countless other phrases.

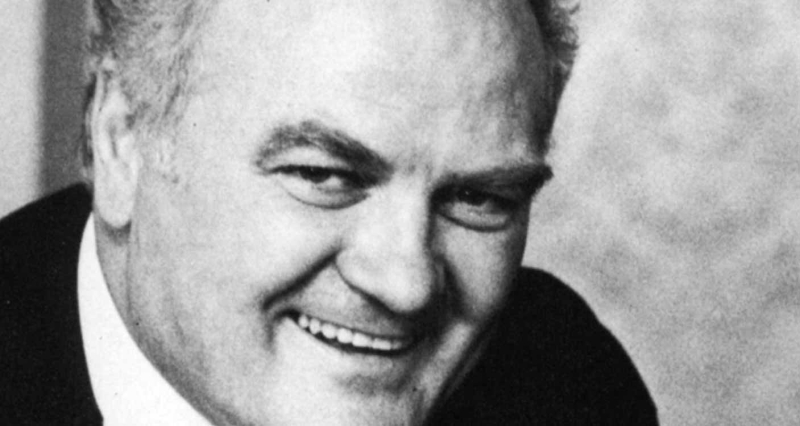

Stuart Skelton’s Siegmund seemed to me to stand firmly in the top echelon of the role’s interpreters of the last half-century, alongside Jon Vickers and James King. Both musically and as a character, this role suits Mr. Skelton far better than Otello. His Siegmund has both power and poetry. The son of a god, he is deeper and more thoughtful than he might seem on the surface; for, in his own way, Siegmund has great nobility…and great humanity. In finding and liberating Sieglinde, he finds a joy and purpose in life hitherto denied him; that it will last less than a day makes him all the more poignant. His overwhelming tenderness towards his sister-bride, his awe in encountering Brunnhilde, and his helpless rage at his father’s deceit are all vividly expressed in his music. And Mr. Skelton took all of this to heart: with generous lyricism, warmth of tone, and vivid declamation, he brought Siegmund palpably to life, making him the central figure of the opera.

Mr. Skelton’s Sword Monolog in Act I was among the very finest I have ever heard. But even before that, he had so many wonderful passages of clear-voiced, expressive singing: ” Kühlende Labung…”, and the great subtlety and feeling of resignation he brought to “Nun weißt du, fragende Frau, warum ich Friedmund nicht heiße!”

The mysterious, uneasy orchestral prelude to the Monolog set the mood for our tenor, who caught every nuance of the text and brought vocal colors into play with masterful modulations of dynamic. Sublime tenderness at “…ein Weib sah’ ich, wonnig und hehr...” was followed moments later by Mr. Skelton’s phenomenal sustaining of the cries of ” Wälse! Wälse!“, so tonally steady and true, whilst the orchestra generated white heat. The trumpet then rang out with the Sword Motif. Magnificent moments!

The tenor’s energy seemed to flag momentarily after these arduous pages of dramatic singing, but he quickly attained peak level again with a beautifully poetic “Winterstürme“. From thence, Mr. Skelton and his Sieglinde, Eva-Maria Westbroek, gave a strikingly passionate account of the final pages of Act I, from the growing excitement as they begin to realize who they are, (Skelton’s “Du bist das bild das ich in mir barg” – “Yours is the image I held in my heart!”…yet another perfect moment) thru the drawing of the sword from the tree, and their escape into the night.

Ms. Westbroek’s singing overcame the distractions of a widening vibrato and insecurity at the top of her range by sheer willpower: her passionate commitment to the music and to the character made her vocal flaws seem irrelevant. The soprano’s rendering of the narrative “Der Männer Sippe” had its vocal ups and downs, but underlying her singing was this deep raging fire: a hope for freedom…and love. This more than compensated for a lack of ‘ring’ in her upper notes. “Du bist der Lenz” likewise had many lovely touches along the way: and then the A-flat loomed. She got it.

Sieglinde describes the sensation of having heard Siegmund’s voice before, as a child; and then, at “Doch nein! Ich hörte sie neulich” (“But no, I heard it of late…”) Ms. Westbroek suddenly cut loose vocally, as if liberated. This launched a magnificent outpouring of emotion and song from both singers as the sibling-lovers surrendered to the inevitable. The soprano staked out a long, resounding top-A as she named Siegmund. And the music rolled on, in an unstoppable flood of hope and desire.

A titanic ovation rocked the house and, as has long been a tradition at this point, the two singers – Ms. Westbroek and Mr. Skelton – stepped out for a bow as the crowd went wild. Günther Groissböck, our excellent Hunding, joined them and the applause re-doubled. It seemed like old times.

Mr. Groissböck (above) is not a cavernous-toned basso in the manner of Martti Talvela or Matti Salminen; the Groissböck Hunding is leaner and meaner. His voice has power, authority, and insinuation. Having patiently listened to Siegmund’s tale of woe, the basso kicks out the blocks with “Ich weiß ein wildes Geschlecht!” and delivers a knockout punch with “Mein Haus hütet, Wölfing, dich heute…” Bravissimo!

Jamie Barton’s Fricka was prodigiously sung; the top notes sometimes have a slightly desperate feel, and to me her over-use of chest voice runs counter to the character: she is the queen of the gods, not a desperate, ex-communicated Sicilian peasant. Barton’s parting lines to Brunnhilde were more to the point: a self-righteous woman calmly dealing from a position of power; a wife who has the upper hand.

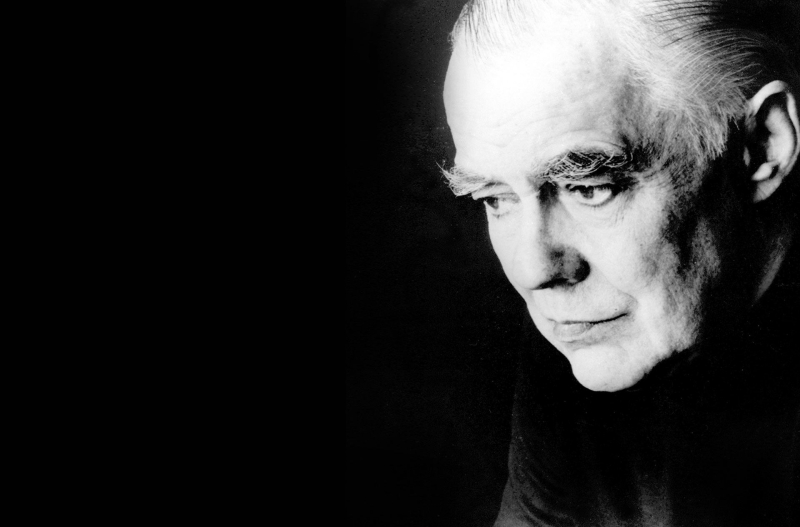

Greer Grimsley’s voice is now rather time-worn, but he knows the role of Wotan inside-out and makes a vibrant impression through his deep understanding of the character, using the words as a dramatic springboard, and hurling vocal thunderbolts at just the right moments. His long monolog in Act II was rich in detail and feeling, and his dismissal of Hunding was a memorable moment: “Geh!” first as a quiet command, then in a snarling fit of rage.

A lot of water has flowed under the bridge of time since Christine Goerke gave her revelatory performances of the Dyer’s Wife in FRAU OHNE SCHATTEN at The Met in 2013. At that time, the huge Met contract she was offered following her triumph seemed both exciting and amply justified. But the ensuing seasons, during which Goerke has put her voice to unstinting use in the most demanding repertory, have taken a toll: notes above the staff are thinned out and approximated now, the power of the voice has lessened, and today there were passing pitch difficulties in the mid-range. Perhaps to compensate, the soprano seemed to be over-enunciating the text, spitting out and biting off her words.

The soprano got off to a rocky start with a helter-skelter Battle Cry. But Ms. Goerke settled in for the opera’s heart and soul: the Todesverkundigung (Annunciation of Death), where the music lies very much in her comfort zone. Maestro Jordan took this scene a bit faster than I’d have liked, and sometimes let the voices be covered. The music is full of foreboding as Brunnhilde tells Siegmund he will die in the coming fight against Hunding, after which she will bear him to Valhalla; there, as Ms. Goerke beautifully tells him, he will be greeted by Wish-Maidens who will serve and delight him.

When Siegmund asks if Sieglinde can come with him into the afterlife, Brunnhilde/Goerke replies – meltingly lovely of tone – “Erdenluft muß sie noch athmen” (“Earthly air must she keep breathing…”). Siegmund then rejects the bliss of Valhalla. When Brunnhilde chides him for placing his love for this “poor, ailing woman” above the glory of immortality, Siegmund’s reply is one of the great crushing dismissals in all opera:

“So young and fair you shine before me,

yet how cold and hard is your heart!

If you can only mock me,

then take yourself hence,

you cruel, merciless maid!

Or if you hunger for my distress,

then freely feast on my woe;

let my grief quicken your envious heart:

But of Valhalla’s loveless raptures

speak no more to me!”

No mortal has ever answered Brunnhilde thus; now, moved by Siegmund’s plight and her eyes opened to her father’s deceit, Brunnhilde vows that Siegmund shall win the coming fight.

This leaves the stage now to Mr. Skelton’s Siegmund. Gearing up for the battle, he looks upon the sleeping Sieglinde and sings – with infinite tenderness: “So slumber on, till the fight be fought, and we find our peace and joy!”

The ominous blaring of Hunding’s hunting horns is heard. And the fight is on! The voices of Skelton and Groissböck – so alive in the House – threaten one another. The orchestra storms wildly. Brunnhilde shields Siegmund, but Wotan suddenly appears out of nowhere, shatters Siegmund’s sword, and Hunding slays his enemy with a spear thrust. Pausing only to dispatch Hunding, Wotan/Grimsley turns his wrath on his disobedient daughter, who has fled with Sieglinde and the pieces of the shattered sword:

“But Brünnhilde! Woe to that traitor!

Dearly shall she pay for her crime,

if my steed o’ertakes her in flight!”

Metropolitan Opera House

March 30th, 2019 matinee

DIE WALKÜRE

Richard Wagner

Brünnhilde..............Christine Goerke

Siegmund................Stuart Skelton

Sieglinde...............Eva-Maria Westbroek

Wotan...................Greer Grimsley

Fricka..................Jamie Barton

Hunding.................Günther Groissböck

Gerhilde................Kelly Cae Hogan

Grimgerde...............Maya Lahyani

Helmwige................Jessica Faselt

Ortlinde................Wendy Bryn-Harmer

Rossweisse..............Mary Phillips

Schwertleite............Daryl Freedman

Siegrune................Eve Gigliotti

Waltraute...............Renée Tatum

Conductor...............Philippe Jordan

~ Oberon