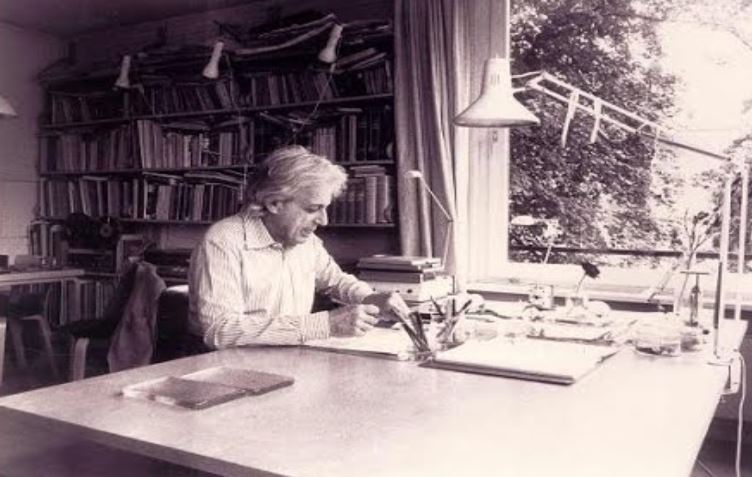

Above: pianist Pedja Mužijević, photographed by Jacob Blickenstaff

~ Author: Oberon

Tuesday June 12th, 2018 – Works by Johannes Brahms, Robert Schumann, and Clara Schumann were on offer as musicians from the Orchestra of St Luke’s joined pianist Pedja Mužijević in this concert at Merkin Hall which is part of a series entitled Facets of Brahms.

Johannes Brahms, Clara Schumann, and Robert Schumann were close friends and confidantes. Schumann had pronounced Brahms the heir of Beethoven, marking him out as third of the Three Bs. Following Schumann’s mental deterioration and his eventual death in an asylum, Brahms and Clara continued a flirtatious friendship that endured for many years.

Johannes Brahms’ Scherzo from the Sonatensatz in C-Minor was the composer’s share in an 1863 collaborative musical gift for the violinist Joseph Joachim; Robert Schumann and Albert Hermann Dietrich each contributed movements of their own.

In this evening’s performance, violinist Krista Bennion Feeney joined Mr. Mužijević. We were seated very close to the stage, and at the Scherzo‘s animated start, the sound of the piano seemed often to overwhelm the violin. Ms. Bennion Feeney is a subtle artist, and it took a few moments for the balance between the two instruments to be achieved. Thereafter, the performance became distinctive, with alternating currents of passion and lyricism. Ms. Bennion Feeney’s arching tonal glow in the central violin theme was most appealing; the piece then moves on to a big finish.

Returning with cellist Myron Lutzke – whose playing with the St Luke’s orchestra has often endeared itself to me – the violinst and pianist gave a wonderfully simpatico rendering of the Schumann Piano Trio No.1, Op. 63. Mr. Lutzke’s dusky timbre and his Olde World cordiality of style seemed beautifully matched to Ms. Bennion Feeney’s superb control of dynamics whilst Mr. Mužijević at the Steinway reveled in the many marvelous piano passages Schumann has provided.

The opening movement is marked, “Mit Energie und Leidenschaft” (‘With energy and passion’). Throughout the first movement, achingly expressive passages from the violin over piano arpeggios alternate with dramatic outbursts. The cello’s incursions are relatively brief but telling. A change of mood near the end builds slowly to a kind of grandeur. Deep tones from the cello then have a calming effect, before another build-up leads to a return to the first theme, now altered and lovingly styled by Ms. Bennion Feeney. The music flows on to a rather unusual minor-key finish.

The second movement has a lively, scherzo-like quality. Its repeated rising theme and sense of rhythmic drive have a wonderfully familiar feeling. The rising motif returns in the Trio section, although here it is slower and more thoughtful. Violin and cello sing up and down the scale, then we zoom back to the original ascending theme, to a sudden ending.

Marked “Langsam, mit inniger Empfindungen” (‘Slowly, with inner feeling’), the third movement ravishes with a poignant violin melody, the cello providing a tender harmony. Things grow more animated; the violin hands over the melody to the cello and their voices entwine. This music drew me in deeply as it lingered sadly, with sustained low cello notes. The movement ends softly, and the three musicians went directly into the Finale, with its joyous song. An exhilarating rush to the finish brought warm applause for the three players.

As the audience members returned to their seats after the interval, it was apparent that our neighbors had stepped out for a cigarette: the smell was dense and unpleasant. We made a quick dash to the balcony where the usher was welcoming. We found a quiet – though chilly – spot from which to enjoy the concert’s second half.

Ms. Bennion Feeney and Mr. Mužijević’s radiant performance of Clara Schumann’s Romances for Violin, Op. 22, assured that Frau Schumann’s music more than held its own when set amidst that of her more celebrated husband and the masterful Brahms.

From its lovely start, the first Andante molto has a sense of yearning, the violinist bringing both depth of tone and gentle subtlety. Lightness of mood marks the Allegretto, with its passing shifts to minor, decorative trills, and a wry ending. A lilting feeling commences the final movement, melodious and – again – modulating between major and minor passages. The piano takes up the melody, and all too soon the Romances have ended.

Ms. Bennion Feeney and Mr. Mužijević rounded out their busy evening with the Brahms Horn Trio, Op. 40, joined by Stewart Rose. Mr. Rose’s tone can be robust or refined, depending on the musical mood of the moment. A few passing fluffed notes go with the territory: as a frustrated horn-player, I know it all too well.

I did find myself wishing that the violinist and horn player had been seated during this piece; I think it makes for a more intimate mix with the piano. The music veers from the pastoral to the poignant, from rich lyricism to sparkling liveliness, and the ‘hunting horn’ motifs in the final Allegro con brio always give me a smile. The three players made this quintessential Brahms work the crowning finale of a very pleasing evening.

~ Oberon