~ Author: Shoshana Klein

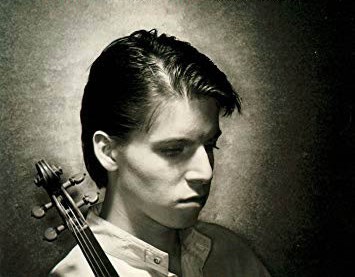

Above: composer Lera Auerbach takes a bow, applauded by the conductor, Manfred Honeck. Photo by the author.

Wednesday December 3rd, 2025 – I have (mostly) fond memories of hearing the Pittsburgh Symphony regularly when I was in undergrad – as a music student, you’re expected to attend often – what better way to learn from your teachers than to hear them perform live every weekend?

There have been some notable roster changes since then – concertmaster Noah Bendix-Bagley left for Berlin, prompting a long search for someone to fill those large (though young) shoes. A few years ago, principal bassoonist Nancy Goeres retired – I was excited to hear her replacement, Julia Harguindey. More recently, Lorna McGhee, principal flute, left for Boston, which is a huge loss for the wind section–every time I heard her I was amazed at her tone. In much more niche news, I miss my oboe teacher, Scott Bell, trustily sitting second throughout my years there. He’s happily retired and likely busy playing Bridge. Really, much of the orchestra has turned over since 2018 or so, and not to their detriment!

The evening’s program:

LERA AUERBACH Frozen Dreams (NY Premiere)

RACHMANINOFF Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini

SHOSTAKOVICH Symphony No. 5

This extremely standard program started off with one thing less well–known: the commissioned piece Frozen Dreams by Lera Auerbach. The composer framed the piece in an interesting and philosophical way in the program notes – the tension between music being both static and different for every listener. The piece had great textures and rhythms – marimba or waterphone paired with string pizzicato was a great effect – and the piece used pitch bends, lots of string harmonics texturing, and some complicated hocketing – almost all executed very well.

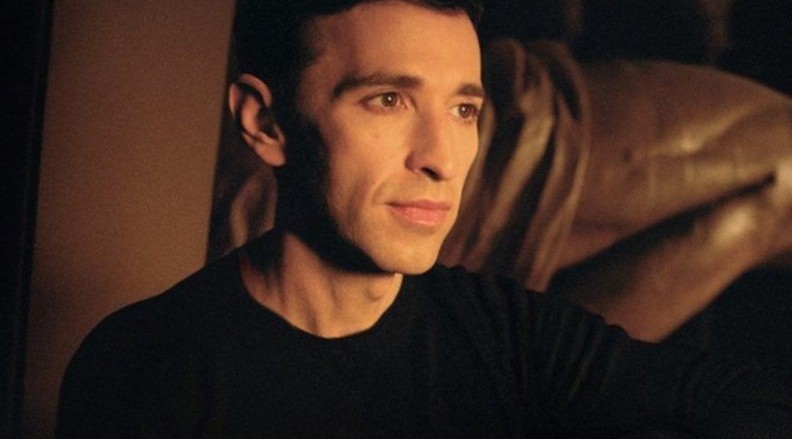

The Rachmaninoff started off a little stronger than I was expecting – not as timidly as it could in order to build, and not at all slow either, one of the earlier variations almost leaving the winds behind. Pianist Seong-Jin Cho was great – I don’t know of him but he seems masterful, especially with the full bodied orchestra behind him. I always forget how the familiar themes of this piece sneak their way in. The piece briefly showed off Max Blair, sounding great as always as assistant principal, as did English horn player Tim Daniels.

The flagship movement – the sappy climax of the piece – was balanced well, not at all over the top but still engaging, from both soloist and orchestra. A well-deserved encore was a delicate Chopin Waltz (C-sharp minor). Cho played it very subdued with sparingly used builds towards important moments – really a treat.

Shostakovich’s 5th Symphony hits differed in our own brand of fascism – I always end up reading program notes, even when I know the history of a piece. These were particularly well done, explaining the controversy between this piece being a “propaganda symphony” and an act of defiance and truth in Soviet Russia.

The first movement gives opportunities to hear most of the winds. Those who have been there forever still sound amazing and look exactly the same as I remember, and the new bassoonist and guest principal flute player sounded great.

The second movement took me by surprise – conductor Manfred Honeck took a lot of liberty with the time, stretching things and breathing a lot of life into it. Perhaps some of this was not having listened to the piece in quite a while, but it felt fresh and exciting.

Cynthia DeAlmeida – with whom I am well acquainted and got to say a quick hello to afterward, does get a mention for her solo in the 3rd movement – very worth paying attention to (even if you’re not in undergrad trying to soak up as much oboe playing as you can), with a very present and shimmery tone. Mike Rusinek took over the solo on the clarinet with a much more translucent sound. Pittsburgh’s strength has always been its soloistic and individual solo wind players, and that certainly hasn’t changed.

The fourth movement started fast to my ear – I heard a story about Bernstein and this piece, that he misread or misinterpreted a tempo marking and ended up doing the accelerando at the end of the piece in double time (who knows if this is accurate, but it does end very fast in his recording). This interpretation started fast and ended very slowly! I always thought the speed up added to the feeling of frenzy, that there was something to cover up, emotionally – but I guess intentional slowness could do the same thing.

In conclusion, the PSO is still a wind-forward orchestra and even better than before with some turnover. I know some of my enjoyment of this concert was nostalgia, but I can’t help but be impressed!

~ Shoshana Klein