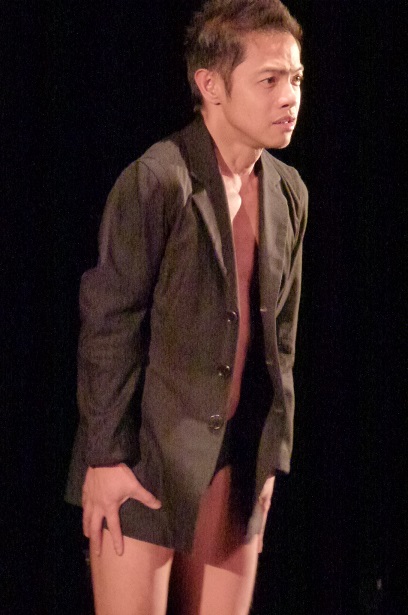

Above: soprano Dina Kuznetsova

Tuesday February 18, 2014 – An evening of Polish songs, presented by New York Festival of Song at Merkin Hall, offered an opportunity to hear music I’d never heard before. Michael Barrett and Steven Blier were at the Steinways as tenor Joseph Kaiser opened the evening with “Nakaz niech ozywcze slonko” from Stanislaw Moniuszko’s Verbum Nobile; to a march-like rhythm, Mr. Kaiser poured forth his rich-lyric tone with some strikingly sustained high notes. Soprano Dina Kuznetsova made her first appearance of the evening singing Edward Pallasz’s “Kiszewska” (a ‘lament of the mother of mankind’); intimate and mysterious at first, this song takes on a quality of deep sadness for which the singer employed a smouldering vibrato.

Four songs by Grazyna Bacewicz represented a wide spectrum of vocal and expressive colours: Ms. Kuznetsova in three of the songs ranged from reflective to chattery, at one point doing some agitated humming as she expressed the numbing horror of having a severe headache. Mr. Kaiser’s rendering of “Oto jest noc”, a song to the moon, was powerfully delivered with some passages of vocalise and a big climactic phrase.

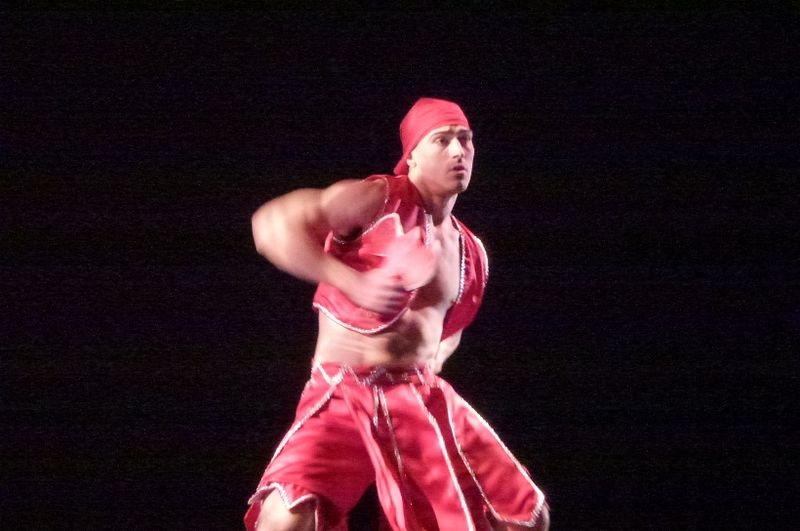

Above: tenor Joseph Kaiser

Each singer represented a song by Mieczyslaw Karlowicz: the tenor in the touchingly melodic “Mów do mnie jeszcze” (‘Keep speaking to me…’) with its rising passion so marvelously captured by the singer; and then the soprano in the composer’s very first published song “Zasmuconej” (‘To a grieving maiden…’) with its simple, poetic melody showing Ms. Kuznetsova’s communicative gifts with distinction.

Mieczyslaw Weinberg’s Seven Yiddish Songs were composed in 1943 to texts by the great Yiddish writer, I. L. Peretz. Weinberg, whose life was lived under the dark clouds of anti-Semitism (his entire family destroyed in a concentration camp with the composer having fled to Russia in 1939), is only now experiencing a renaissance with his 1968 opera THE PASSENGER having been recently performed at Bregenz and Houston and due to be seen in New York City this Summer. This evening’s performance of the Seven Yiddish Songs, Opus 13, was my first live encounter with Weinberg’s music.

The cycle commences with a child-like “la-la-la-la” duet and proceeds with solos for each singer; another duet takes the form of a playful dialogue. Things take a darker turn as Mr. Kaiser sings of an orphaned boy writing a letter to his dead mama; in the closing song “Schluss” the piano punctuates Ms. Kuznetsova’s musings. Both singers excelled in these expressive miniatures.

Two more Moniuszko songs: a flowingly melodic ‘Evening Song’ with an Italianate feel from the tenor, and a ripplingly-accompanied, minor-key ‘Spinning Song’ delivered with charm by Ms. Kuznetsova.

Mr. Blier spoke of Karol Szymanowski’s homosexuality and how it coloured much of the composer’s work. In four songs, the two singers alternated – first the soprano in a quiet, sensuous mood and then Mr. Kaiser singing with increasing passion in a Sicilian-flavored ‘”Zuleikha” (sung in German). Ms. Kuznetsova employs her coloristic gifts in one of the Songs of the Infatuated Muezzin, a cycle inspired by Szymanowski’s visit to North Africa. In ‘Neigh, my horse’ from The Kurpian Songs Mr. Kaiser tells of a rider, en route to his beloved, being distracted by another beauty he meets on the journey; the tenor’s voice rose ringingly to a clarion climax which faded as he sent his riderless horse on to reassure his waiting sweetheart.

The evening ended with an operatically-styled ‘Piper’s Song’ by Ignacy Jan Paderewski where the two voices blended very attractively as the duet moved to its shimmering conclusion.

Despite a bit too much talking – and an un-cooperative microphone – and some distracting comings and goings, the evening was an enjoyable encounter with rarely-heard music and the pleasing experience of hearing Ms. Kuznetsova and Mr. Kaiser lift their voices in expresive song.