Above: the artists of today’s esteemed ensemble – Wu Han, Daniel Hope, Paul Neubauer, and David Finckel – at Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center

~ Author: Oberon

Sunday January 27th, 2019 – Four great musicians joined forces this evening at Alice Tully Hall as Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center continued their season with a program of works by Josef Suk, Johannes Brahms, and Antonín Dvořák.

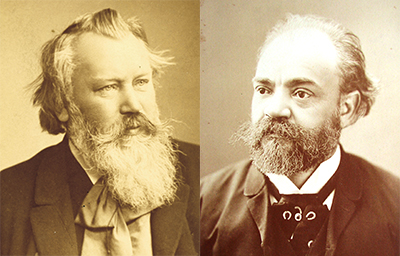

Josef Suk (above), the least-known of the three composers, was a prominent violinist and Dvořák’s son-in-law. Suk’s Quartet in A minor, Op. 1, dates from 1891; it was his first published work.

From its passionate start, with the strings playing a unison theme from which David Finckel’s cello and Daniel Hope’s violin emerge in prominent solo lines, this vivid music abounds in gorgeousness . Wu Han at the Steinway brings the tempo down a bit and a flow of melodies commences. Paul Neubauer’s viola heralds a brief drama – a tempest that soon subsides, though a subtle agitation lingers. Cellist David Finckel’s darkish timbre contrasts with the high silkiness of Mr. Hope’s violin. The strings united provide a rich texture that gives the impression of a full string orchestra in play, whilst Wu Han relishes Suk’s appealing writing for the piano. A passage of soul-filling passion brings the first movement to a glorious end.

The extraordinary softness of Wu Han’s touch at the Steinway lures us into the central Adagio. Then a cello theme of great richness is brought forth by Mr. Finckel, taken up by Mr. Hope’s violin singing sweetly on high, echoed by the Neubauer viola. The strings have a beautifully blended passage: luminous playing from all. With the rippling piano and gleaming violin, a feeling of rapture rises up. The music stops, then the cello and piano lead us into a new dream. Violin and viola harmonize as the cello offers a plucked accompaniment. The Adagio – in which the magical essence of chamber music seems to be sublimely enshrined – reaches its heavenly end, fading into bliss.

But there’s no time for reverie: Wu Han launches the concluding Allegro con fuoco at once, the strings offering sharp accents along the way. Later the pianist produces a high shimmer – a sparkling delicacy over which the strings harmonize. Things turn folkish, with a gypsy dance getting quite expansive before a lull of calm; then on to a grand finish.

This was my second hearing of Josef Suk’s Opus 1 and the second time it has had the same magical effect on my. Why is this composer’s music not heard more often?

Next on the program was Johannes Brahms’ Quartet No. 3, Op. 60 which was written in 1855-56 and revised in 1874. The period in which Brahms began sketching this work was a very difficult time, for his friend Robert Schumann had been confined in a mental hospital; Brahms was in a highly emotional state.

The dramatic, sorrowing phrases that open the Allegro con fuoco attest to Brahms’s troubled spirit. But the music swirls forward on the wings of a piano theme; it becomes almost celebratory but then retreats to a doleful conclusion.

The piano is the motivating force of the ensuing Scherzo; the music is agitated, almost angry. The Andante commences with a long cello solo, expressively played by Mr. Finckel. Mr. Hope then duets with the cello; Mr. Neubauer joins in an entwining string trio; the piano has a lovely part to play. A sense of longing builds.

The concluding Allegro, which begins with a restless motif played by Wu han and Mr. Hope. Far from the traditional upbeat finale, this one by Brahms lingers in a serious, rather pensive mood, ending with an abrupt chord.

After the interval, Dvořák’s Quartet in E-flat major, Op. 87 (1889) was splendidly played. This quartet has its folksong aspects, especially in the outer movements. The opening Allegro con fuoco is thematically abundant, with trade-offs among the string voices and lovely piano passages. After a big, thrilling buildup, the music simmers down; there’s a very effective tremolo motif exchanged by the violin and viola before the first movement comes to its finish.

David Finckel opened the Lento with a poetic cello melody, which is carried onward by Mr. Hope’s violin. The piano has a lyrical part to play here – charmingly rendered by Wu Han – as the themes pass thru sublime modulations. A slow dance commences, with plucked strings, and the movement finds its resolution.

The third movement, Allegro moderato, has the feel of a waltz. From its exciting start, the music presses forward with rustic elements: the piano takes on the aspect of a hammer dulcimer. Mssrs. Hope and Neubauer match subtleties, and the violist has a final say as the movement concludes.

The zesty Finale is a real crowd-pleaser, and, when played as it was tonight, assures itself of a vociferous reaction from an appreciative audience.

For all the excellence of the Brahms and Dvořák, it was the opening Suk that lingered in my mind.

~ Oberon