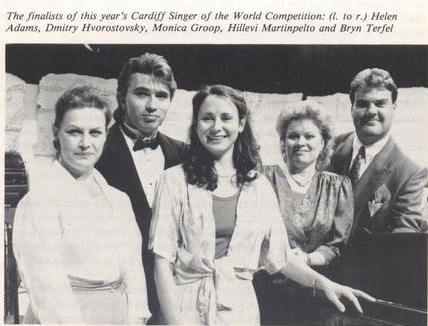

Above, the Miró Quartet: Daniel Ching and William Fedkenheuer (violins), Joshua Grindele (cello), and John Largess (viola). Photo by Naova Ikegami.

~ Author: Oberon

Thursday October 25th, 2019 – For their concert at Weill Hall this evening, the Miró Quartet honored the history of string quartet performance in America by replicating a program performed by the country’s first professional touring string quartet – the Kneisel Quartet – over a hundred years ago.

Franz Kneisel, then concertmaster of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, founded his quartet in 1885. The program offered tonight by the Miró was first performed by the Kneisel in 1910 during the Kneisel Quartet’s 25th anniversary season. The Miró Quartet are celebrating their own 25th anniversary this season, so the connection has layers of meaning.

The first half of tonight’s concert was beset with extraneous distractions; following an over-long interval, the Miró took the chill off a hall that had become frigid due to A/C overload with their sizzling performance of Schubert’s Death and the Maiden.

Mozart’s “Hunt” quartet, K.458, opened the evening. The Miró’s violinists faced one another, with the cellist and violist in the middle. Right from the music’s joyous start, a wonderful vitality could be felt in the quartet’s music-making. Daniel Ching’s trill tickled the ear, and a five-note motif was passed from player to player with wit and sparkle. A gracious interlude and a paragraph in the minor key were so persuasively delivered.

The cordial mood the Miró had established was then spoilt by late seating. It took a while for things to re-settle in the hall. There were more latecomers allowed in later. Very distracting.

The Menuetto: Moderato profited from lovely depth of tone from each player. The ensuing Adagio has the feel of a melancholy bel canto aria, with a tender melody sung first by the violin and then taken up by the cello. As the movement continued, with exquisite playing from Mr. Ching, the sound of quiet snoring crept into our collective consciousness. I could not tell if the players could hear it or not. At any rate, they carried on with the sprightly start of the final Allegro assai, the cellist reveling in his rich tone, everything lively and appealing.

The Kneisel Quartet were advocates for contemporary works of their day; thus music by Reinhold Glière and César Franck was on the program; it felt odd to hear only parts of string quartets by these two composers, but it seems that the idea of playing individual movements of works was not frowned upon in 1910.

Each of the three remaining works on the program’s first half was prefaced by a spoken introduction from one of the players. As there was a very thorough program note about the content of the concert, the talking seemed unnecessary.

The Glière Andante (his Opus 1, #2) and the Franck Scherzo were delightfully played. The Glière is a ‘theme-and-variations’ affair, launched by the viola and cello playing pizzicati under sustained tones from the violins. A gently rocking feeling takes over, with decorative fiorature from the violin; then the music turns fast and furious, with the brisk, deep cello bringing a sense of urgency. Ethereal sounds from the violin next lend a pensive air – very subtle playing here – and then a dance springs up, with plucking lower voices and shivering violins.

The Franck Scherzo, the shortest movement of his lengthy D-major Quartet, brought forth mutes for the violins, lending the charming piece a magical lightness akin to Mendelssohn’s faerie music.

In another departure from ‘normal’ string quartet programming, the unusual inclusion of a work for cello and piano on tonight’s program points up yet again how things were sometimes done back in the day. Pianist Stephanie Ho joined the Miró’s cellist Joshua Gindele tonight for Adrien-François Servais’ Fantasie sur deux air Russes.

The cellist and pianist are long-time friends and colleagues, so their playing was beautifully meshed and simpatico. Ms. Ho commenced the work with a solemn opening piano statement. The first cello melody, oddly familiar, was lushly played. And then, with a delicious trill from Mr. Gindele, a dance strikes up, and it soon turning into a gallop. The cello goes very high, and then very low. Following some hesitations, a sad waltz develops. This leads to a virtuoso competition between cello and piano…great fun! After a few small detours, comes the brilliant finish. The two musicians embraced as the audience warmly applauded their expert performance.

Returning after the prolonged interval, the Miró Quartet swept aside any and all distractions or concerns with a thrilling rendering of Schubert’s immortal Death and the Maiden.

The opening Allegro drew vibrant playing from the Miró. The individuality of the players’ respective timbres achieves a surprisingly coherent, compelling blend: they make this familiar music sound fresh – and what more can we ask? Their rhythmic surety and variety of dynamics make their playing irresistible.

The sublime Andante con moto, which introduces the doleful “Death” theme, moved me deeply with its air of hushed lamenting. The emotional ebb and flow of this movement seemed to well up from Mr. Gindele’s richly resonant cello, suffusing the whole with a spiritual glow.

The Scherzo is quite brief; we don’t know if Wagner intentionally lifted one rhythmic motif here to serve as a leitmotif for Nibelheim in his opera DAS RHEINGOLD, but it always gives me a smile.

Now the finale is reached, with Mr. Ching festooning the music with precise filigree over the passion and drive of his colleagues’ playing. A high-velocity rush suddenly shifts into hyper-gear as the music careens almost recklessly to its end.

Playing at the peak of their powers, the dazzling Miró artists turned the concluding Presto into the crowning glory of this outstanding musical experience. Though “death’ is in the work’s title, the word I kept scrawling in my notes about the Miró’s playing was: “…alive..!”

~ Oberon