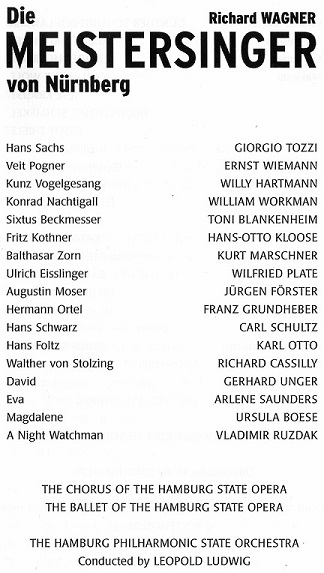

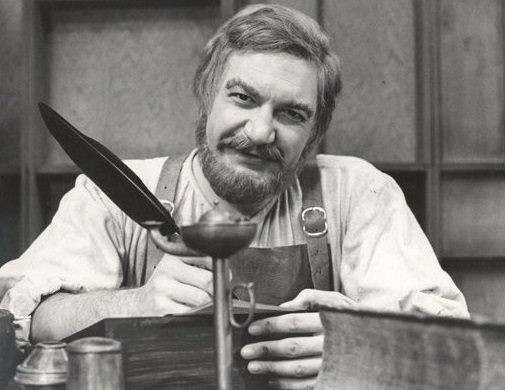

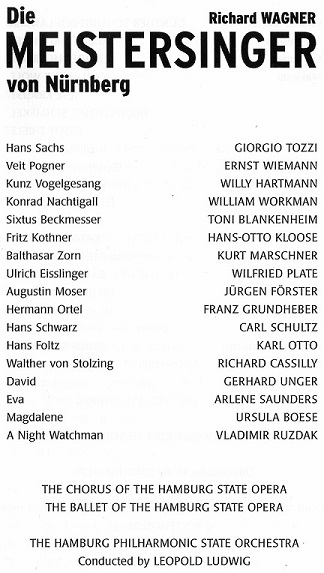

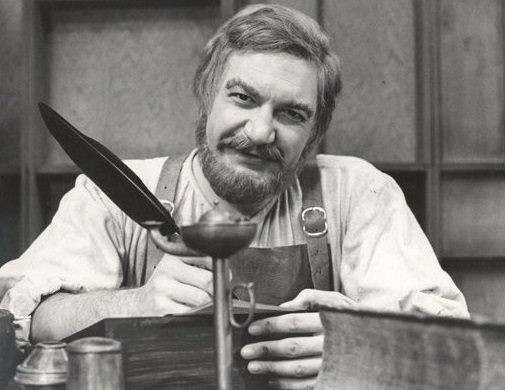

Above: Giorgio Tozzi as Hans Sachs and Richard Cassilly as Walther von Stoltzing

Author: Oberon

I plucked a DVD of Wagner’s Die Meistersinger off the shelf at the Library of the Performing Arts; it was described as a “studio production from the Hamburg State Opera, 1970”. I had no idea what to expect, but I ended up really loving it.

Purists will kvetch over the fact that about 25 minutes of music has been cut, including parts of David’s long monolog in Act I and the Apprentices Dance in Act III. The cuts were apparently made so as to conform to the four hours allotted for a television presentation. Since the David is very fine, and since the overall performance is excellent, it’s too bad that the cuts had to be made. They did not, however, affect my great enjoyment of the performance.

Sets are ‘suggested’ rather than built. The opera is fully staged, in appropriate costumes; the singers appear to be lip-syncing to a pre-made recording, and they all do a splendid job of it…so good, in fact, that you can’t really tell.

Leopold Ludwig leads a stylish reading of the overture; throughout the performance, he sets perfect tempi and ideally balances the comedy and chaos against the intimacy, passion, and humanity that pervade this marvelous opera.

The filming makes us part of the action. In Act I, the lively apprentices tease David whilst setting up for the meeting of the Masters: we are part of their work and their play. The apprentices, by the way, are a handsome bunch of boys, each with his own personality. In live performances, petite women from the chorus are sometimes pressed into service in this ensemble group, so as to sing the higher-lying phrases. Here, the boys seem to tackle those lines in falsetto.

Once the masters have convened, we are right in the thick of their debates: the camera sweeps and zooms in as opinions are expressed and reactions are caught on film. An expert bunch of singing-actors, we get a vivid feeling of each Master as an individual. And later, we even go inside the Marker’s curtained booth as Walther von Stoltzing sings his heart out in his trial song…to no avail.

The conversations, comings and goings, furtive lovers’ meetings, and Beckmesser’s silly serenade (mistaking ‘Lene for Eva) in Act II lead up to a convincingly bumptious “riot”. In Act III, the intimate scene of Sachs urging Stolzing onward in the composing of the “Prize Song”, and of Beckmesser’s pilfering of said song, and of the blessèd joy of the great quintet, gives way to the meadow on St. John’s Day – a vast space with only a gallery for the Masters, a chair for Eva, and the platform from which the “Prize Song” becomes an immortal melody. The triumph of true love is celebrated by all.

The cast is superb in every regard. Each singer has the measure of his or her role, both vocally and in characterization. There’s little in terms of theatricality to come between us and these folks as real townspeople, and the story unfolds with complete naturalness.

Giorgio Tozzi is for me simply a perfect Hans Sachs; he was, in fact, the very first singer I saw in this role at The Met in 1968. More than that, Tozzi played a huge part in my developing passion for opera: the first basso voice I came to love, his arias from NABUCCO and SIMON BOCCANEGRA were on the first operatic LP set I every acquired; he was Don Giovanni in the first opera I attended at the (Old) Met, and later he was my first Daland and Jacopo Fiesco. I saw Tozzi onstage for the last time as Oroveso in NORMA at Hartford, CT, in 1978; he was so vivid as the almost deranged high priest of the Druids.

Here in this MEISTERSINGER film, Tozzi (above) is everything I want in a Sachs: vocally at ease in every aspect of the wide-ranging music, his singing warm, his portrayal so human and so rich in detail. His two monologs (Flieder– and Wahn-) are beautifully sung and deeply felt, and his impassioned final address to the citizens of Nuremberg – a warning against the intrusion of foreign powers on their daily lives – rings true today. It is so pleasing to have Tozzi’s magnificent Sachs preserved for the ages.

Arlene Saunders (above, as Eva) is another singer to whom I feel a strong attachment, as well as a sense of gratitude: over a span of time, I saw Ms. Saunders singing four vastly different roles, making a memorable impression in each. First was her Anne Trulove when the Hamburg Opera brought THE RAKE’S PROGRESS came to The Met in 1967; Ms. Saunders’ pealing lyricism in her aria and ‘cabaletta‘ left such a lovely impression. Later, she was a surprisingly thrilling Minnie in FANCIULLA DEL WEST at New York City Opera, a movingly vulnerable and hopeful Elsa in LOHENGRIN at Hartford’s Bushnell Auditorium, and strikingly beautiful, touching, and wonderfully-sung Marschallin at Boston.

In this Hamburg MEISTERSINGER, we first see Saunders’ adorable face looking up from her prayer-book in church, secretly thrilled by the attention of the tall knight who is captivated by her. From there to the end, Ms. Saunders endears and charms us in every moment of the role of Eva.

Richard Cassilly (above, with Ms. Saunders as Eva) is an imposing and big-voiced Stolzing; he towers over his beloved Ev’chen, and indeed over most everyone in the film. Often seeming stiff and dour, the tenor blossoms into smiles whenever Eva is near. The knight’s pride, insecurity, and hopefulness are all expressed in Mr. Cassilly’s acting; as to his singing, it is big, warm, and winning. The scene of the ‘birth’ of the “Prize Song” – and of Eva’s hearing it for the first time – is very moving to an old romantic like myself.

Toni Blankenheim (above, with Giorgio Tozzi as Sachs at the end of Act I) scores in one of his greatest roles, Beckmesser. In the hands of such an imaginative singing-actor, this annoyingly vain character finally moves us in Blankenheim’s portrayal of his defeat. The baritone also convinces us that he is actually playing the lute. (There is apparently a similar filmed production from Hamburg of Berg’s WOZZECK with Blankenheim in the title-role and Sena Jurinac as Marie; I want to see it!)

Above: Gerhard Unger and Ursula Boese as David and Magdalene

Petite of build, tenor Gerhard Unger with his boyish face does not seem out of place among the apprentices. Unger is a first-rate, “voicey” character singer and an impetuous actor. As his slightly older betrothed, Magdalene, Ursula Boese is wise and warm-hearted whilst also being a sly conspirator in getting everything to go well for Eva and Stolzing. Both Unger and Boese sing very well indeed.

Basso Ernst Wiemann (above) sang nearly 75 performances at The Met from 1961 to 1969, including the roles of Fafner, Hunding, Hagen, the Commendatore, Rocco, King Henry, and Daland in broadcasts of these operas that I was hearing for the very first time. As Pogner in this film of MEISTERSINGER, Wiemann displays his ample, seasoned basso tones in a warmly paternal portrayal.

The one singer in a major role with whom I was totally unfamiliar is Hans-Otto Kloose (above), who plays an upbeat, gregarious Kothner. In both his portrayal and his singing, Mr. Kloose excels. He was a beloved member of the Hamburg State Opera ensemble for thirty years, starting in 1960, giving more than 1,800 performances with the Company. For all that, I cannot seem to find other samples of his singing.

The Meistersingers include both veterans and jünglings: among the latter, Franz Grundheber is an extremely handsome Hermann Ortel. As a final link among the singers in this film to some of my earliest operatic memories, Vladimir Ruzdak, who sang Valentin in my first FAUST at the Old Met, appears here as a baritonal Nightwatchman.

“All’s well as ends better,” as they say in The Shire. Sachs is crowned with a laurel wreath by Eva at the feast of St. John’s Day in Olde Nürnberg.

~ Oberon