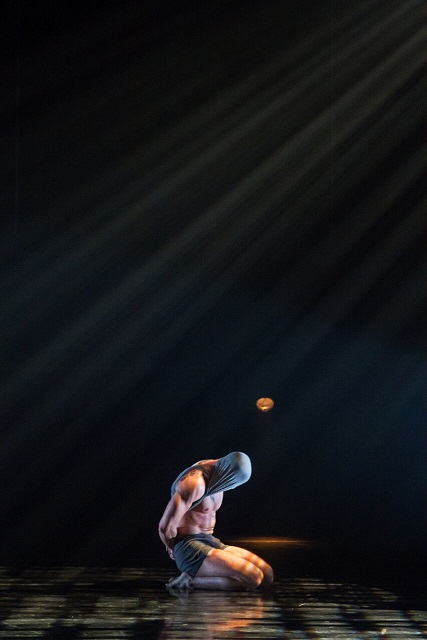

Above: the Schumann Quartet

Sunday February 26th, 2017 – Following last week’s Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center‘s program centering on joy-filled music by Felix Mendelssohn, we were back at Alice Tully Hall to experience the great composer’s more melancholy moods. With music of Bach and Schumann also on offer, we became acquainted with Schumann String Quartet, and could admire once again three artists whose CMS performances to date have given particular pleasure: violinist Danbi Um, cellist Jakob Koranyi, and pianist Juho Pohjonen.

Mr. Pohjonen (above) opened the evening with Bach’s Chromatic Fantasy and Fugue in D minor for Keyboard, BWV 903. The Finnish pianist’s elegance of technique and his Olde World mystique always summon up for me visions of pianists from bygone days performing in the drawing rooms of Paris, Budapest, or Vienna. But for all those dreamworld allusions, Mr. Pohjonen’s playing has vibrant immediacy and is very much of our time.

Mr. Pohjonen, in a program note, describes the Chromatic Fantasy as “labyrinthine”, and that it most surely is; but it’s a wonderful work to get lost in, and as the pianist drew us along the music’s sometimes eccentric, almost improvisational pathways, we could only marvel at the gradations of both subtlety and passion in his playing.

The Schumann Quartet intrigued us from the very opening notes of their rendering of Mendelssohn’s Fugue in E-flat major. From her first phrase, violist Liisa Randalu drew us in; the three Schumann brothers – Erik and Ken (violins), and Mark (cello) – take up the wistful melody in turn. The music becomes gently animated, with the four voices blending serenely. Poignant colours from the rising violin and the honeyed resonance of the cello frame Ms. Randalu’s expressive playing. These textures will become key elements in the Schumann Quartet’s performance of the composer’s Quartet in F-minor, which followed immediately.

Mendelssohn’s last completed major work, the F-minor quartet was composed in 1847. On returning to Frankfurt from a tiring stay in London in early May, the composer soon learned that Fanny, his beloved sister, had died of a stroke. Mendelssohn struggled that summer with work on numerous projects, but was only able to complete this final quartet, dedicated to Fanny’s memory. On November 4th, he died following a series of strokes. He was 38 years old.

The F-minor quartet opens with scurrying attacks and a sense of restless energy. The music softens to a nervous pulsing as the cello sings from lyrical depths, with the luminous violin overhead. The movement then accelerates to a striking finish. The “scherzo” ironically mixes passionate phrases with delicate commentary. Viola and cello rumble darkly in the brief trio passage, then the tempest stirs up again before a little coda vanishes into thin air.

A simple song that Mendelssohn and Fanny had shared in happier times memorializes their bond in the touching Adagio, which commences with a descending cello passage. The recollections evoked by the song, which is a sweet melody in its own right, are now tinged with sadness. Superbly controlled tone from Erik Schumann’s violin was most affecting; the pulsing cello then heralds a surge of despairing passion.

The finale is restless, at times verging on dissonant. Passing notions of lyricism are swept away, and wild passages for the violin warn of an impending disaster. This is a composer on the brink.

The Schumann Quartet’s very impressive playing of this disturbing yet strangely beautiful piece earned them a very warm acclamation from the Tully Hall crowd. It is pleasing to know that they will be back with us next season in this same lovely space to share other aspects of their artistry – music from The Roaring Twenties on March 4th, 2018, and a full Schumann Quartet evening on April 29th, 2018, when they’ll play works of Haydn, Bartok, Reimann, and Schumann.

Following the interval, Mr. Pohjonen offered Robert Schumann’s Arabesque in C major for Piano, Op. 18. This episodic piece has a narrative aspect, though none is stated or even implied. Mr. Pohjonen relished the melodious themes that rise up, veering from major to minor as the Arabesque flows forward. Subtle passages become treasurable in this pianist’s interpretation, and the poetic finish of the work was lovingly expressed.

Juho Pohjonen returned with his colleagues Danbi Um and Jakob Koranyi for Schumann’s Trio No. 1 D minor for Piano, Violin, and Cello, Op. 63.

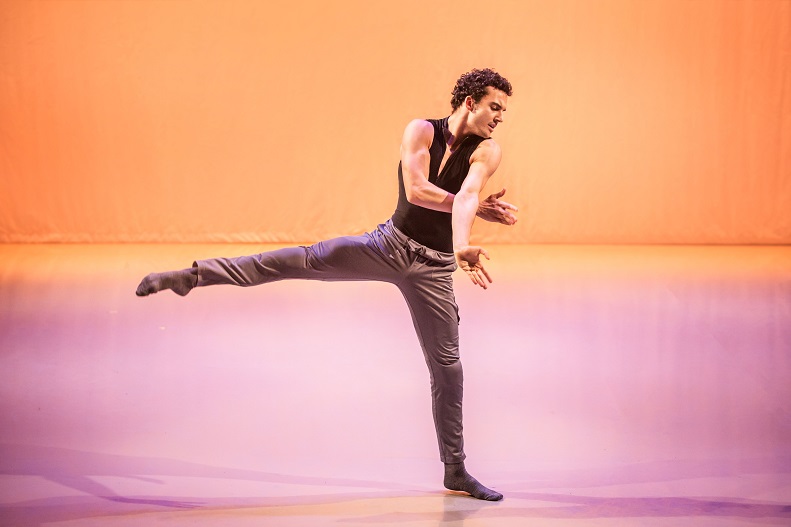

Above: Danbi Um, photo by Vanessa Briceño

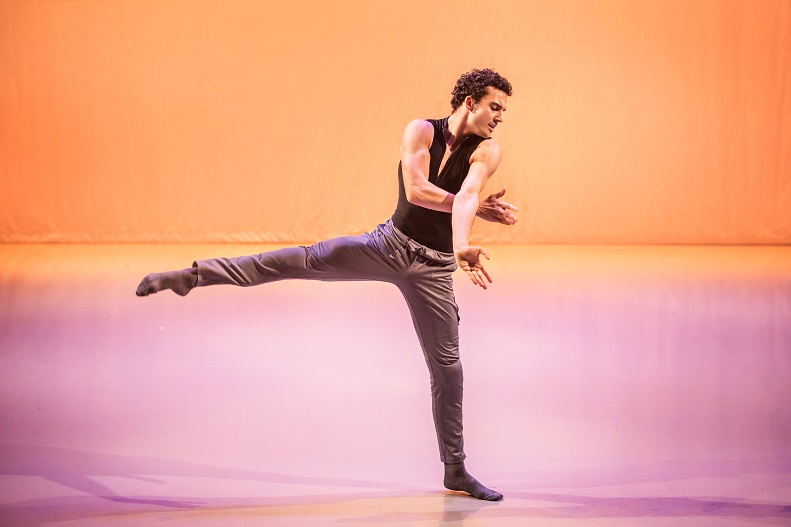

Above: Jakob Koranyi, photo by Anna-Lena Ahlström

Ms. Um, lithe and lovely in a fair burgundy-hued gown, displayed the sweetness of tone that makes listening to her so enjoyable; Messrs Koranyi and Pohjonen are masters of dynamic nuance, and thus the three together delivered page after page of radiant, colorful playing.

The D-minor trio’s opening movement calls for rippling arpeggios from the pianist, expertly set forth by Mr. Pohjonen. Ms. Um and Mr. Koranyi harmonize and converse in passages which switch from lyrical yearning to emphatic declamation. A pause, and a new theme emerges: delicate at first, then turning passionate. A sense of agitation prevails in this movement, despite ‘settled’ moments: the three musicians captured these shifts of mood so well, and they savored the rather unexpected ending.

Marked “Lebhaft, doch nicht zu rasch” (‘Lively, but not rushed’), the scherzo has the feel of a scuffing, skipping dance. Rising and falling scales glow in the calmer interlude; but the dance soon strikes up again…and comes to a sudden halt.

The trio’s third movement embarks on a disconsolate violin passage, played with affecting expressiveness and lovely control by Ms. Um. When Mr. Koranyi’s cello joins in, this simple melody becomes increasingly touching. A gently urgent central section reverts to the slow, sad gorgeousness so evocatively sustained by our three musicians, the cello sounding from the depths.

The tuneful finale seems almost joyous, but shadows can still hover. The playing is marvelously integrated, becoming tender – almost dreamy – with smoothly rippling piano and the violin on the ascent. The themes mingle, developing into a big song. This simmers down briefly before a final rush of energy propels us to the finish.

I had felt pretty certain the Um-Koranyi-Pohjonen collaboration would produce memorable results, and I was right. We must hear them together again – soon – and let’s start with my favorite chamber works: the Mendelssohn piano trios. The audience shared my enthusiasm for the three musicians, calling them back for a second bow this evening.

- Bach Chromatic Fantasy and Fugue in D minor for Keyboard, BWV 903 (before 1723)

- Mendelssohn Fugue in E-flat major for String Quartet, Op. 81, No. 4 (1827)

- Mendelssohn Quartet in F minor for Strings, Op. 80 (1847)

- Schumann Arabesque in C major for Piano, Op. 18 (1838-39)

- Schumann Trio No. 1 D minor for Piano, Violin, and Cello, Op. 63 (1847)