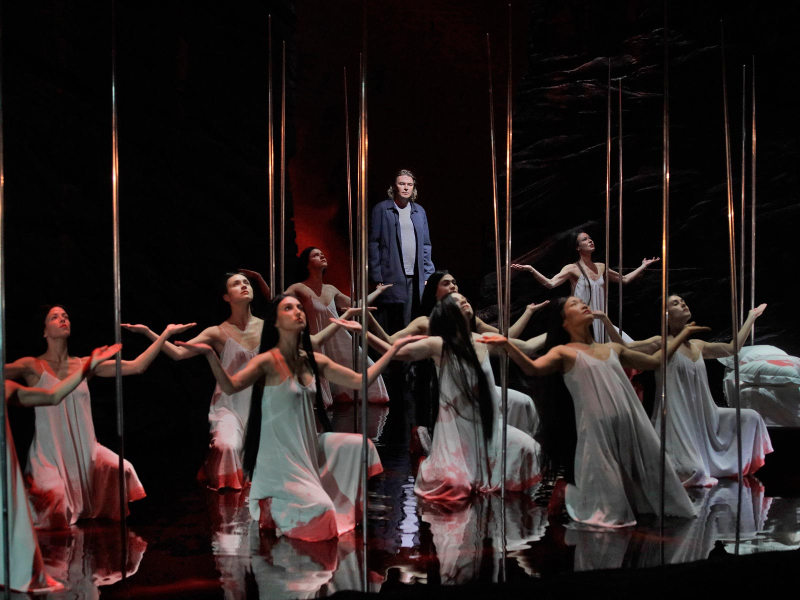

Above: the Grail revealed: Peter Mattei as Amfortas and Rene Pape as Gurnemanz in Wagner’s PARSIFAL; a Ken Howard/Met Opera photo

~ Author: Oberon

Saturday February 17th, 2018 matinee – A powerful and thoroughly absorbing matinee performance of PARSIFAL, the only Wagner in the Metropolitan Opera’s repertory this season. This dark, barren, and brooding production premiered in 2013, at which time the total absence of a Grail temple from the scenic narrative seemed truly off-putting. All of the action of the outer acts takes place out-of-doors, whilst the second act – as we were told by someone who worked on the production at the time it was new – is set inside Amfortas’s wound.

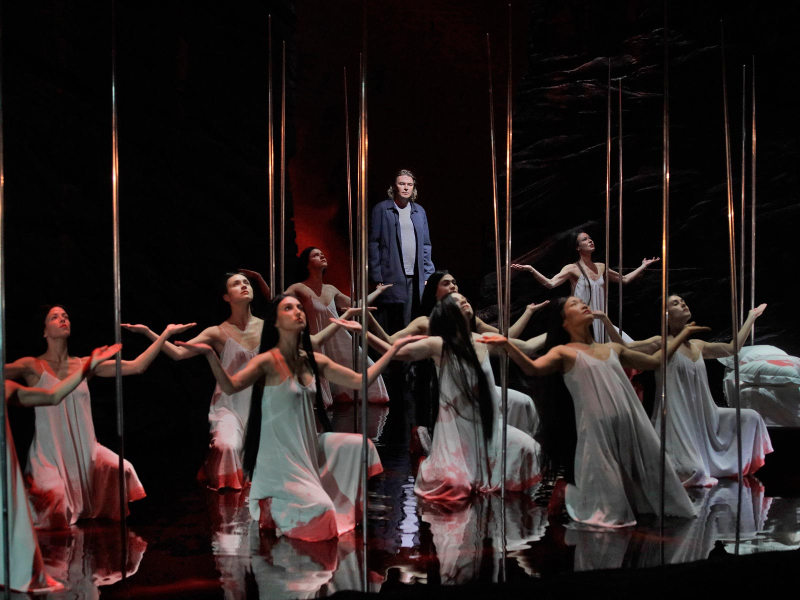

Not everything in the production works, and the desolate landscape of the final act – with its open graves – is dreary indeed. But the devotional rites of the Grail brothers in Act I and the stylized movements of the Flowermaidens in the blood-drenched ‘magic garden’ of Act II are engrossing – especially today, where I found a personal link to both scenes.

Musically, it was a potent performance despite a couple of random brass blips. Since the 2013 performances, I’ve been going to a lot of symphonic and chamber music concerts and this has greatly enhanced my appreciation of the orchestra’s work whenever I am at the opera. From our perch directly over the pit today, I greatly enjoyed watching the musicians of the Met Orchestra as they played their way thru this endlessly fascinating score.

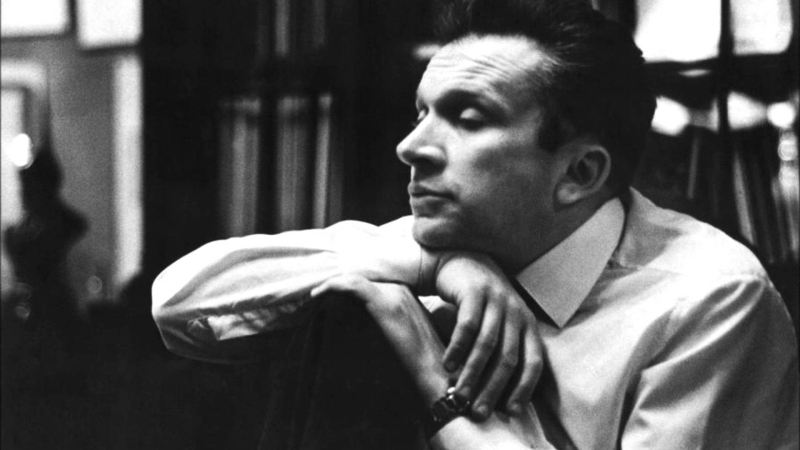

The Met’s soon-to-be music director, Yannick Nézet-Séguin, was on the podium this afternoon, and he seemed to inspire not only the orchestra, but also the principals, chorus, dancers, and supers all of whom worked devotedly to sustain the atmosphere of the long opera. While I did not feel the depth of mystery that I have experienced in past performances of this work conducted by James Levine or Daniele Gatti, in Maestro Nézet-Séguin’s interpretation the humanity of the music seemed to be to the fore. This meshes well with the physical aspects of the production, which strongly and movingly depicts the fraternity of the Grail and the desperate suffering of Amfortas. The orchestra’s poetic playing as Gurnemanz sings of the slaying of the swan was but one passage of many where I felt the music so deeply. And the transformation music of Act I was particularly thrilling to hear today.

The singing all afternoon was at a very high level, with the unfortunate exception of the Kundry of Evelyn Herlitzius. We’d previously heard her as Marie in WOZZECK, but Kundry’s music – especially in Act II – needs singing that has more seductive beauty than Ms. Herlitzius delivered. The soprano’s one spectacular vocal moment – “Ich sah Ihn – Ihn – und…lachte!“, where she tells how she had seen Christ on the cross and laughed – was truly thrilling, but not enough to compensate for her tremulous, throaty singing elsewhere.

Above: In Klingsor’s Magic Garden, tenor Klaus Florian Vogt as Parsifal; a Met Opera photo

In 2006, Klaus Florian Vogt made an unforgettable Met debut as Lohengrin, and this afternoon as Parsifal the tenor again sang lyrically in a role that is normally sung by tenors of the more helden- type. The almost juvenile sound Vogt’s voice underscored Parsifal’s innocence; this worked especially well in Act I, and also brought us some beautiful vocalism in Act II. As Kundry’s efforts to seduce become more urgent, Vogt’s singing took on a more passionate colour. In his struggle between steadfastness and capitulation, the tenor’s cry of “Erlöse, rette mich, aus schuldbefleckten Händen!” (‘Redeem me, rescue me from hands defiled by sin!’) pierced the heart with his dynamic mastery.

Kundry’s wiles fail her, and with an upraised hand, Parsifal fends off Klingsor’s spear-wielding assault. Seizing the weapon that wounded Amfortas, the young man cries out “Mit diesem Zeichen bann’ ich deinen Zauber!” (‘With this Sign I banish your magic!’); the bloody back-lighting dissolves to white and Klingsor is cast down. Turning to Kundry, Mr. Vogt’s Parsifal has the act’s final line of premonition: “Du weisst, wo du mich wiederfinden kannst!” (‘You know where you can find me again’) and he strides out into the world to commence his long, labored journey back to the realm of the Grail. In the final act, Mr. Vogt’s expressive singing was a balm to the ear, lovingly supported by the conductor and orchestra.

Above: Rene Pape as Gurnemanz, in a Ken Howard/Met Opera photo

Repeating the roles they created when this production premiered in 2013, Rene Pape (Gurnemanz) and Peter Mattei (Amfortas) were again superb. Mr. Pape now measures out his singing of this very long part more judiciously than he has in the past, at times allowing the orchestra to cover him rather than attempting to power thru. But in the long Act I monolog, “Titurel, der fromme Held…”, the basso’s tone flowed like honey; and later, at “Vor dem verwaisten Heiligtum, in brünst’gem Beten lag Amfortas...” (‘Before the looted sanctuary, Amfortas lay in fervent prayer’) Mr. Pape’s emotion-filled delivery struck at the heart of the matter. Throughout Act III, leading to the consecrational baptism of Parsifal, Mr. Pape was at his finest.

Peter Mattei’s Amfortas (in a Ken Howard/Met Opera photo above) is truly one of the great operatic interpretations I have ever experienced, for it is not only magnificently sung but acted with matchless physicality and commitment. The guilt and suffering Mr. Mattei conveys both with his voice and his body is almost unbearable to experience in its intensity and sense of reality.

After a desperate show of resistance to calls for the Grail to be revealed in Act I, Amfortas – in abject anguish – performs the rite; his strength spent, he staggers offstage and as he does so, he locks eyes with Parsifal, the man who will succeed him as keeper of the Grail: one of the production’s most telling moments. And in the final act, Mr. Mattei throws himself into the open grave of his father, Titurel, as he begs for death to release him from his eternal suffering; this horrifies the assembled Grail knights. Such moments make for an unforgettable interpretation, yet in the end it’s the Mattei voice that sets his Amfortas in such a high echelon.

Evgeny Nikitin’s Klingsor (above), creepy and thrilling in 2013, incredibly was even better in this revival. The voice was flung into the House with chilling command, and the bass-baritone’s physical domination of his bloody realm and his hapless female slaves was conveyed with grim authority. His demise was epic.

Alfred Walker sang splendidly as the unseen Titurel, and I was very glad that he appeared onstage for the bows so I could bravo him for his wonderful outpourings of tone. Another offstage Voice, that of Karolina Pilou – who repeats the prophetic line “Durch Mitleid wissend…der reine Tor!” (‘Enlightened through compassion, the innocent fool…’) to end Act I – had beauty of tone, though the amplification was less successful here.

The Squires ( Katherine Whyte, Sarah Larsen, Scott Scully, and Ian Koziara) were excellent, especially as they harmonized on the emblematic “Durch Mitleid wissend…” theme, and the Flowermaidens sounded lovely, led with ethereal vocal grace by Haeran Hong. Mark Schowalter and Richard Bernstein were capital Knights, and I must again mention Mr. Bernstein’s terrific voice and physical presence as a singer underutilized by the Met these days. His lines ths afternoon were few, yet always on the mark; and in Act III, helping to bear the shrouded body of his late lord Titurel to its grave, Mr. Bernstein seemed to carry the weight of the world on his shoulder.

What gave the performance a deep personal dimension for me today was finding two dancers I have known for some time – David Gonsier and Nicole Corea – onstage in Acts I and II respectively. By focusing on them – Mr. Gonsier as a young Grail knight and Ms. Corea as a delicious Blumenmädchen – the ‘choreography’ given to these two groups became wonderfully clear and meaningful.

I first spotted Mr. Gonsier seated in the circle of knights; my imagination was immediately seized by the rapture evident in his eyes. For long, long stretches of the first act, I could not tear my gaze away from him as his mastery of the reverential gestural language and the deep radiance of his facial expressions spoke truly of what it means to be a knight of the Holy Grail. Amazingly, out of all the men I might have zeroed in on among the brotherhood, Mr. Gonsier was the last of the knights to leave the stage as Act I drew to an end: he received a personal blessing from Gurnemanz and their eyes met ever-so-briefly. So deeply moving.

Ms. Corea is beloved in the Gotham danceworld for her work with Lar Lubovitch; I ran into her on the Plaza before the performance today and she assured me I’d be seeing her this Spring at The Joyce as Mr. Lubovitch celebrates his 50th anniversary of making dances. Incredibly, within two seconds of the Act II curtain’s rise on the identically clad and be-wigged Flowermaidens standing in a pool of blood, I found Nicole right in my line of vision. Both in her compelling movement and her captivating face, Nicole became the icon of this band of bewitching beauties.

Whilst hailing some of the unsung cast members of the afternoon, mention must be made of the two heroic supers who literally keep Amfortas alive and mobile, frequently taking the full weight of the ailing man as he struggles to fulfill his dreaded duties as Lord of the Grail. Great work, gentlemen!

Much of the libretto of PARSIFAL‘s outer acts today seems like religious mumbo-jumbo. It’s the music – especially the ending of Act I – that most clearly speaks to us (and even to an old atheist like me) of the possibility of God’s existence. Perhaps He has simply given up on mankind, as His name – and his word – have been sullied in recent years by those very people who claim to revere him. Wagner may have foreseen all this, as he once wrote: “Where religion becomes artificial, it is reserved for Art to save the spirit of religion.”

At the end of Act I of today’s PARSIFAL, I momentarily questioned my disbelief. But then the applause – which I’ve always hated to hear after such a spiritual scene – pulled me back to reality. I’d much rather have stayed there, in Montsalvat.

Metropolitan Opera House

Saturday February 17th, 2018 matinee

PARSIFAL

Richard Wagner

Parsifal................Klaus Florian Vogt

Kundry..................Evelyn Herlitzius

Amfortas................Peter Mattei

Gurnemanz...............René Pape

Klingsor................Evgeny Nikitin

Titurel.................Alfred Walker

Voice...................Karolina Pilou

First Esquire...........Katherine Whyte

Second Esquire..........Sarah Larsen

Third Esquire...........Scott Scully

Fourth Esquire..........Ian Koziara

First Knight............Mark Schowalter

Second Knight...........Richard Bernstein

Flower Maidens: Haeran Hong, Deanna Breiwick, Renée Tatum, Disella Lårusdóttir, Katherine Whyte, Augusta Caso

Conductor...............Yannick Nézet-Séguin

~ Oberon