As Summer began to transition into Autumn, I found myself with less time for my favorite solitary pastime: listening to recordings of live performances of the operas of Richard Wagner. But I spent a long time with a 1975 Bayreuth GOTTERDAMMERUNG, re-playing certain scenes repeatedly. It’s one of the most exciting performances of that opera I’ve ever heard.

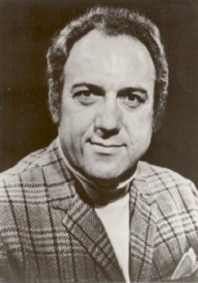

The overall majesty of this GOTTERDAMMERUNG owes a great deal to the masterful conducting of Horst Stein (above). Under his remarkable leadership, the performance drew me in from the opening chord. Not only is the great span of the work honored in all its epic magnificence, but time and again Maestro Stein illuminated what I thought were familiar passages with fresh nuances of colour or dynamic.

As the First Norn, Marga Höffgen’s voice wells up from the mysterious glow of the prelude. Höffgen (pictured above) is authoritative and she sent a shiver up my spine with the line “Die nacht weicht…” (“The night wanes…”) sung with such a prophetically gloomy resonance. Wendy Fine as the Third Norn has a strong sense of urgency in her singing, and Anna Reynolds as the Second Norn is simply superb: in voice, diction and expression she brings a thrilling dimension to this music.

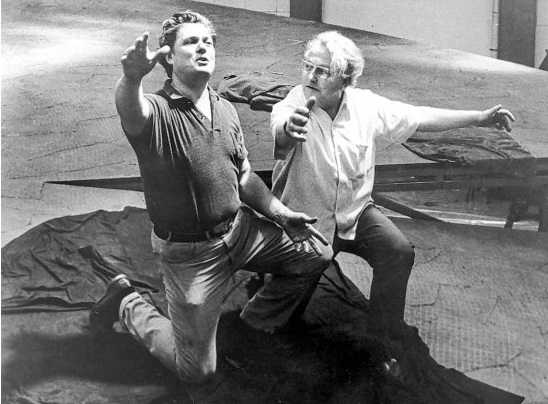

Horst Stein’s spacious reading of the Dawn Music has a triumphant ring, heralding the only truly happy scene in the entire opera. Catarina Ligendza and Jean Cox as Brunnhilde and Siegfried are splendidly matched, she showing a full-bodied sense of lyricism whilst the tenor’s strong, sustained singing will be a boon to the entire performance. Stein builds the rapture of their duet exctingly, a big vocal outpouring worthy of the passions they express…passions soon doomed to betray them.

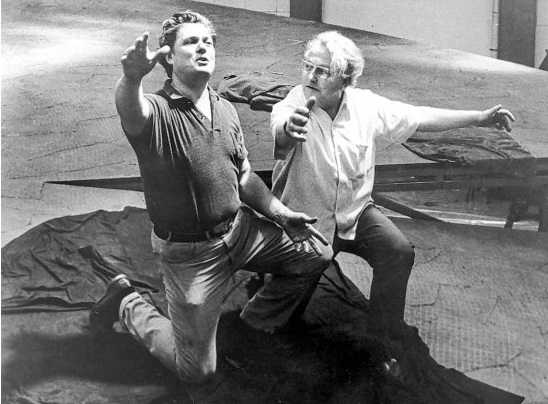

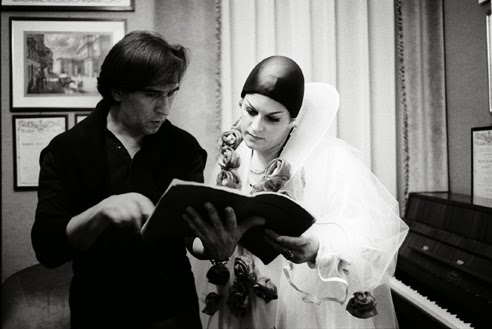

Above: Jean Cox rehearsing at Bayreuth with Wolfgang Wagner

A wonderful rocking feeling pervades Stein’s reading of the Rhne Journey; we feel like we’re in Siegfried’s boat, along for the joyride. The threesome we meet at the Gibichung Hall are as strong a trio as one could hope for: power and pride of voice from Franz Mazura (Gunther), rich lyricism from Janis Martin (Gutrune), and the start of a masterful performance of Hagen from Karl Ridderbusch.

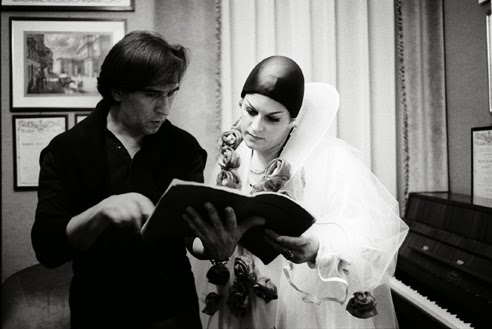

Ms. Martin (above, with Claudio Abbado) started out singing smallish roles at The Met, eventually having a major career as a Wagnerian soprano. She was my first Sieglinde, Kundry, and Marie in WOZZECK, and she really makes her mark here as Gutrune. She, Mazura, and Ridderbusch share a strong sense of verbal detailing, keeping the dramatic situation in sizzling high-profile; Cox and Mazura are very powerful in the Blood Brotherhood scene; they sail off to the Valkyrie Rock, leaving Ridderbusch to deliver a simply magnificent rendering of Hagen’s Watch, thrillingly abetted by Maestro Stein.

Above: Anna Reynolds

The scene is now set for some truly remarkable singing in the confrontation between Brunnhilde and her sister Waltraute, played by Anna Reynolds. Ms. Reynolds is a great favorite of mine; she was my first RHEINGOLD Fricka (conducted by Herbert von Karajan at a Metropolitan Opera matinee…his only Met broadcast), and a few seasons later I had the good fortune to also experience her WALKURE Fricka. All of the things I love about Reynolds’ singing are in ample evidence in this GOTTERDAMMERUNG: her timbre is truly beautiful, her registers even; she is dynamically alert and verbally keen, a very subtle colourist with a sense of majestic authority, later overcome by despair as Brunnhilde refuses to part woth the Ring. The argument between Reynolds and Ligendza is masterfully developed by Maestro Stein, Ligendza standing her ground with firm-voiced dignity. Reynolds concludes the scene on a splendid top A-natural and rushes away.

As the flames surrounding her abode leap up. Ligendza brings great lyric joy to her anticipated reunion with Siegfried; her despair at his betrayal and her realization of his deceit are finely delineated by Stein and his orchestra; the conflict and Siegfried’s brutal seizing of the Ring are excitingly realized by the singers and conductor.

![Neidlinger-Gustav-02[Saul-881] Neidlinger-Gustav-02[Saul-881]](https://oberonsglade.blog/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/8de928e61dac39e52f99903868aa90b2.jpg)

Above: Gustav Neidlinger, a fabulous Alberich

Maestro Stein commences the second act with a throbbingly sinister prelude which leads to the appearance of Alberich (Gustav Neidlinger), manifesting himself in a dream to his son Hagen. This is one of my favorite scenes in the RING Cycle, and Neidlinger and Ridderbusch give it a tremendous impact, their singing and verbal nuances meshing to great expressive effect. Neidlinger (famed for his portrayal Alberich on the classic Georg Solti commercial RING) so vividly captures the restless insistence of the dwarf, desperate of regain the ring and depending on Hagen to achieve it. Throughout the scene, the two singers receive superb support from Stein.

Janis Martin makes the absolute most of every line Wagner gives to Gutrune, and then Karl Ridderbusch unleashes a tremendous “Hoi ho!”, grandly summoning his vassals to celebrate the arrival of Gunther’s bride. The chorus’s excitement seems genuine as they sing “Gross gluck und Heil!”; of course, the festive throng soon fall into epic puzzlement as the downcast Brunnhilde appears, escorted by Gunther. Mazura’s potent singing and rugged sense of nobility will make his downfall all the more tragic. The chorus, amazed by Brunnhilde’s stupor, whisper “Was ist ehr?” (“What ails her?”); the answer comes soon enough.

Catarina Ligendza shows very slight traces of vocal fatigue in this strenuous act, but scarecly enough to be a demerit to the overall impact of her portrayal. Even when somewhat taxed, she plunges bravely onward. The swearing of the oaths – potently underscored by Stein – finds the soprano a bit stressed here and there, and Mr. Cox fudges the brief high-C. But none of this really detracts from the overall thrill of the performance. As Siegfried and Gutrune leave to prepare for the ceremony, Ligendza is back on fine form in expressing Brunnhilde’s uncomprehending woe and then her unbridled fury. Mazura limns Gunther’s shame with disturbing intensity and when Brunnhilde heaps insults in him, he is filled with self-loathing. Ligendza, Mazura, and Ridderbusch then join in the final trio which bristles with dramatic fire, fanned marvelously by Maestro Stein and the orchestra.

The excellence continues with Act III: Horst Stein’s scene-painting is colourful and detailed, and I love his trio of Rhinemaidens: they blend very well, and you can hear each voice distinctly in the harmonies. Elisabeth Volkmann (Woglinde) sings so prettily, and Inger Paustian (Wellgunde) makes a fine impression as she spies the ring on Siegfried’s finger.

I’m particularly happy to have this souvenir of Sylvia Anderson (above), a singer I heard at New York City Opera in the 1970s as Octavian and as Giovanna Seymour in ANNA BOLENA. As Flosshilde, she gives a lovely mellow depth to the Rhinemaidens’ trios; it’s really nice hearing her voice again.

Unlike some Siegfrieds, Jean Cox has plenty of voice left to spend going into Act III. He really sings: no barking or hoarseness. Calling out to the hunting party from which he has wandered, Cox produces a walloping long high-C, a note most Siegfriends can’t even hit at this point in a long evening; it’s not beautiful, but it’s such a heroic touch.

In the ensuing scene, building up to the murder of Siegfried, Ridderbush is simply superb and Mazura remarkably vivid in lines that some baritones throw away. Siegfried’s narrative has a real lilt to it, and Cox is first-rate: yest abother distinctive passage from this imperturbable performer. The orchestral playing continues to shine, movingly supporting the tenor as he regains his senses after Hagen’s spear-thrust has laid him low. This leads to a grand and glorious rendering of the Funeral March by Stein and his tireless players.

Back at the Gibichung Hall, Janis Martin is again very impressive as she awaits the return of the men. The ensuing scene, with her horror at Siegfried’s demise, Hagen’s crude cruelty, and Gunther’s shame and remorse, is filled with tremendous tension: brilliant work from Martin, Mazura and Ridderbusch, ideally underscored by the valiant Maestro.

And now it’s left to Catarina Ligendza (above) to bring this mighty performance to a close with the Immolation Scene. She summons up impressive reserves for this big sing, and although traces of strain are detectable here and there, the overall sweep of the music and the fine support she gets from Stein send her sailing forward. In the great benedictive phrase “Ruhe…ruhe du Gott!” Ligendza is splendid. She then greets Grane with a fabulous top B-flat and finishes very strongly indeed. Maestro Stein brings his masterful interpretation of this epic work to a close with stunning aural vistas of fire, flood, and redemption.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

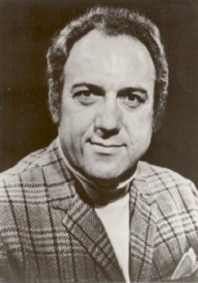

A performance of DER FLIEGENDE HOLLANDER from Vienna 1972 piqued my curiosity, mainly because of the presence of Cornell MacNeil in the title-role. MacNeil first sang the Dutchman in a series of performamces at the Met in 1968, conducted by Berislav Klobucar. His Sentas were Leonie Rysanek, Regine Crespin, and Ludmila Dvorakova. At the time my opera-going friends and I hoped that this would mark the first of many forays into the German repertoire for the voiceful baritone: we imagined him as Kurwenal, Telramund, Wolfram, Amfortas, Hans Sachs, the Wotans, Barak, Orestes, and Jochanaan. But aside from performances as the Dutchman in Seattle in 1972 and then in Vienna in the same year, MacNeil never again sang a German role to my knowledge.

MacNeil’s a most impressive Dutchman on this Vienna issue; if his monolog lacks the palpable sense of mystery and poetic longing that the greatest interpreters bring to this music, his power is ample and his sense of vocal commitment unerring. He is well-matched in Act I by the Daland of Manfred Schenk who sings strongly; the two men’s long duet here always strikes me as Wagner at his most Verdian; their singing of it is grand yet human. Adolf Dallapozza is a clear-voiced Steersman and the chorus respond heartily to conductor Otmar Suitner’s rollicking tempo for their casting-off chorus which ends the act.

Suitner sets Act II deftly in motion with the whirring of the spinning wheels; the choral voices seem girlish.

In a marvelous bit of casting, Margarita Lilowa (above) is a full-voiced, warm-toned Mary. She brings vocal appeal to a role that is often assigned to ‘character’ singers or aging Wagneriennes.

Janis Martin (above), an American mezzo-turned-soprano, loomed large in my opera-going career. A Met Auditions winner in 1962 (she sang Dalila’s “Mon coeur s’ouvre a ta voix” at the Winners’ Concert), Martin sang nearly 150 performances at the Metropolitan Opera, commencing in 1962 as Flora Bervoix in TRAVIATA. As a young opera-lover, I heard her many times on the Texaco broadcasts. She eventually moved on to “medium-sized” roles: Siebel, Nicklausse, Lola in CAVALLERIA RUSTICANA. She left The Met in 1965 and built a career abroad, moving into soprano territory. She returned to The Met and from 1974 thru 1977; in thse seasons, she was my first in-house Kundry, Marie in WOZZECK, and Sieglinde. Another hiatus, and then she was back at Lincoln Center from 1988-1992, singing the Witch in HANSEL & GRETEL, the Dyer’s Wife in FRAU OHNE SCHATTEN, Senta, the Foreign Princess in RUSALKA, and two performances of TOSCA. An interesiting footnote from her second Met TOSCA:

“Because of an injury sustained at her previous performance of Tosca on 10/20/93, Janis Martin did not leap from the battlement at the end of the opera but committed suicide by stabbing herself with the knife she had retained after killing Scarpia in Act II."

Janis Martin sang a single WALKURE Brunnhilde at the Met in 1997, her final performance there. Elsewhere during her career she sang Ariadne, Isolde, and Ortrud.

On this Vienna HOLLANDER, Ms. Martin is thoroughly impressive. She is able to produce a clear, soft lyricism in the more refective passages of Senta’s Ballad and then cut loose with authoritative intensity at the climax.

Like Janis Martin, tenor William Cochran first came to notice as a Met Auditions winner in 1968. At the Winners’ Concert he and co-winner Jessye Norman sang the “Wintersturme” and “Du bist der lenz” from Act I of WALKURE. After singing several performances of Vogelgesang in MEISTERSINGER at The Met in 1968, Cochran went off to build his career and reputation, returning in 1984-1985 for two performances of Bacchus in ARIADNE AUF NAXOS (including a broadcast). You can hear him here in the final scene of Act I of WALKURE with Eileen Farrell. On this Vienna HOLLANDER he’s Erik, the most bel canto of the major Wagnerian tenor roles. He sings clearly and has a feel for the Italianate flow of this two arias.

The scene where Erik describes his nightmare to Senta and she becomes increasingly intense in her reactions – since his nightmare signals her dream come true – is finely played by Cochran and Ms. Martin. And suddenly the object of her obsession appears before her. Mr. Schenk sings his jovial, folkish aria very well – he has no idea where all this is leading. And then Ms. Martin and Mr. MacNeil embark on their great duet, a very taxing piece for both in terms of breath-support, a tessitura that lies high, and the need for expressiveness throughout. MacNeil has a couple off-pitch moments and the soprano is just a trifle tense (but still sucessful) on her highest notes. With Mr. Schenk they drive the trio forward, Ms. Marrtin setting the pace with her high-strung pledge of eternal devotion. There’s no break now leading into the final scene of the opera.

The boisterous chorus and booted dance-steps of Daland’s crew and their call to the Dutchman’s crew to join them are met with eerie silence at first; later when the ghostly sailors begin their hellish chant, the opposing forces mingle violently. Mr. Cochran’s sturdy singing of Erik’s plea cannot dissuade Senta and after hearing Mr. MacNeil’s farewell – laced with heartbreak – and his revelation of his true identity, Ms. Martin sails clearly thru Senta’s high-lying pledge of eternal faithfulness. Maestro Suitner curiously omits the redemption theme from the opera’s closing moments.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Sheer curiosity prompted me to order this disc of excerpts from DIE WALKURE. From the details provided, this peformance seems to have been a broadcast from the Royal Albert Hall of a concert version of the opera, with the orchestra of the Royal Opera House under the baton of Sir Georg Solti. The excerpts are rather oddly chosen: an excellent rendering of Siegmund’s Sword monolog from Act I finds tenor Ernst Kozub at his considerable best. The appetite is whetted for a continuation of the scene, but instead we jump to the final few minutes of Act I, with Claire Watson an urgent Sieglinde and Mr. Kozub ever-impressive.

Then suddenly we are in Act III, with Ms. Watson being first consoled and then inflamed by the sturdy Brunnhilde of Anita Välkki. Especially fine here are the mezzos and altos among the Valkyries as they warn Brunnhilde that her plan to aid Sieglinde’s escape may falter: Maureen Guy, Monica Sinclair, and Elizabeth Bainbridge are simply super.

The main reason to acquire this disc was to hear Forbes Robinson (above), a Covent Garden stalwart and noted Handelian, as Wotan. Back in the 1960s and 70s when I subscribed to the British magazine OPERA, Robinson’s name was everywhere. I was very curious to hear what sort of Wotan he might have been, and the answer – based on this sampling – is: marvelous! His voice is ample, rich, and warm, and he comes storming on in Act III to chastise his beloved daughter. Once the Valkyries have departed, Miss Välkki and Mr. Robinson give a truly moving performance of the opera’s great final scene, abetted with grandeur by Maestro Solti. If the soprano strays from pitch once or twice, her lovely take on Brunnhilde’s mixture of vulnerability and plucky courage is very finely expressed. The basso’s is surely one of the steadiest and most vocally pleasing Wotans I’ve ever heard, making me wish that the second act, with the god’s great monolog, had also been preserved. Robinson’s performance here amounts to a revelation, actually.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

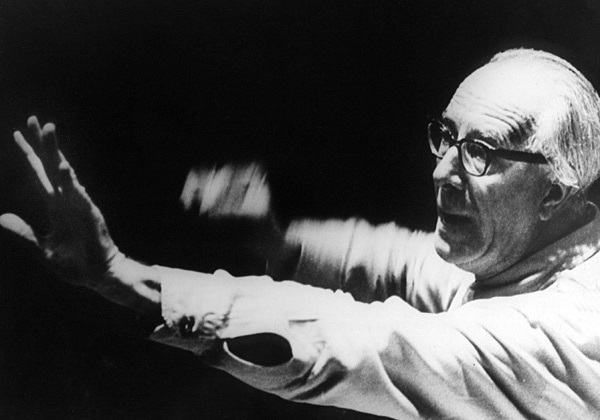

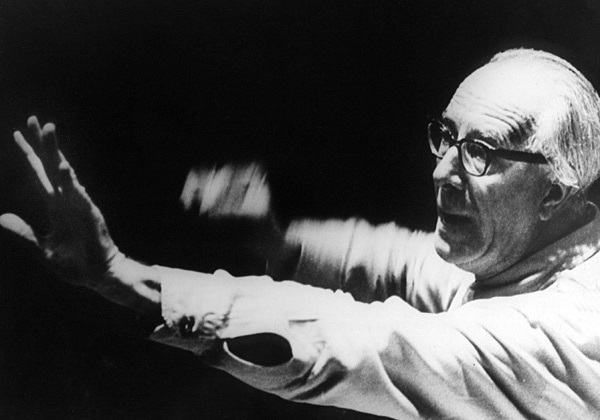

Above: conductor Eugen Jochum

And now that Autumn is slipping into Winter, I set out to select a complete live performance of TRISTAN UND ISOLDE from the several on offer at Opera Depot. I wanted to delve deeper into this opera, which over the years has somehow managed to elude my thorough devotion; my plan was to choose a recording that would hopefully inspire me, and study the score while listening.

After much weighing of pros and cons (it actually took me a couple weeks to make a final choice) I narrowed the list down to three recordings; then the Depot offered one of their 50%-off sales and I made my purchase: the performance is from the Bayreuth Festival 1953, conducted by Eugen Jochum. Within moments of putting the on the first disc, I knew I’d made a perfect choice. It’s a first-class performance in every regard, and the sound quality is very fine indeed.

Maestro Jochum is the great underlying force of this performance. From the opening measures of the prelude, with their pregnant pauses, Jochum steers a monumental course thru this score. The first voice we hear is that of a young sailor, singing from high in the rigging. The tenor is Eugene Tobin, who recently passed away. He does a beautiful job with this plaintive song: a song with a sting in its tail that rouses Isolde from her state of depressed lethargy. And we are off!

Astrid Varnay (above) is for me a very uneven singer. Aside from her recording of ELEKTRA on the Koch label, I don’t have any of her commercial recordings; but I have started to appreciate her more on these Opera Depot releases. I mulled over whether she was the Isolde I wanted to have, and indeed for the first few moments when she starts to sing, I thought that the ‘matronly’ quality I sometimes hear in her singing would be a detriment. But soon she is warmed up and she goes on to give a thrilling performance in every regard. Her lower and mid-range are on exceptional form, and the top notes trumpet out. Her dynamic control is impressive as is her shading of the text.

Ira Malaniuk (above) makes a superb impression as Brangaene, musically and textually detailed and urgently expressive. Her singing throughout Act I is compelling, and she brings a caressive softness to some passages, drawing us in.

Ramon Vinay (above) is both powerfully masculine and poetic as Tristan. As his faithful friend Kurwenal, Gustav Neidlinger barks a bit as he chides Brangaene; later he will reveal his depth of musicality and a gruff tenderness of tragic stature.

We’ve now met the main characters for Act I: Malaniuk returns from her unsuccessful errand to Tristan, and Varnay, at first subtle and then passionate, prepares to unfold her Narrative. Here the soprano is marvelous, the text vividly coloured and the singing rich and secure. Especially gorgeous is her rendering of “Er sah mir in die Augen…” as she describes the troubling glance of the wounded Tantris. Then onwards to a spear-like top B and a blazing, overwhelming curse.

Malaniuk responds with excelling lyricism and a nice, steady top G: the interchanges between her and Varnay tingle with both vocal inspiration and verbal acuity as they discuss the various potions: here Malaniuk’s singing senses the mystery and peril. It’s all thoroughly absorbing.

Varnay is imperious, grandiose as she bids Kurwenal obey his future queen and send Tristan to her at once. She then gives her orders to Brangaene, describing the potions with great intensity; their conversation again bristles with foreboding, and Varnay’s low-A at “Todestrank!” is another marvel. Maestro Jochum now draws forth the ominous build-up to the encounter between Isolde and Tristan.

This scene, which begins with a formal exchange, is perfectly underscored by Jochum’s orchestra: the buildup of tension and passion is spine-tingling, and how cunningly Varnay expresses her reasons for not having killed Tristan. As the drinking of the potion looms – with a loud interjection from the sailors – Varnay’s vocal sorcery and Vinay’s moving sense of nobility are captivating. They drink; their doom is sealed: a flood of tenderness followed by the desperate confusion of the ship’s landing and the lovers torn asunder.

As the acronical second act opens, Malaniuk’s continued perfection and Varnay’s successful lightening of the voice as they discuss Melot keep tension high. Then Brangaene/Malaniuk seeks desperately to dissuade her mistress from extinguishing the torch. Jochum’s thrilling impulsiveness as the lovers finally meet – with Varnay striking some big top-Cs – slowly settles down, and the conductor and his players steep the interlude in a misty perfume. In the love duet, the singers become poets; their urgency waxes and wanes, tenderness and rapture build and then evaporate. Malaniuk’s voice floats her warning over Jochum’s dreamy orchestra. A heroic outpouring from Varnay and Vinay…and then fate intervenes.

Ludwig Weber (above) with his huge, inky voice – full of heartbreak – is very impressive as King Marke, with a flood of painful tenderness as his narrative ends. As Tristan invites Isolde to join him in the realm of darkness, Jochum and Vinay blend is a redolent expressiveness. Then Tristan surrenders himself to Melot’s blade and in a flash, the tragedy is fulfilled.

In his doom-ladened rendering of the opening chords of Act III, Jochum again strikes at the soul. The cor anglais solo is gorgeously played. Gerhard Stolze – well-known for his Loge and Herod – shows off his lyrical aspect as the Shepherd. Gustav Neidlinger’s Kurwenal assumes epic vocal proportions here, deeply moving and drenched with humanity. And Neidlinger’s great joy as Tristan awakens is truly touching.

As madness creeps in and overtakes Tristan, Ramon Vinay veers with aching intensity from wild abandoned to fevered calm. Following a stentorian outburst, Tristan collapses; yet again Neidlinger moves us in expressing his fear that his master has died. Vinay intones a gentle “Wie, se selig”. Then the rising ecstacy as Tristan senses the approach of Isolde’s ship. The shepherd pipes up! Incredible optimism and joy: Kurwenal urges Tristan to live. But in vain: with a single rough-tender “Isolde!”, Tristan expires.

The first hints of the Liebestod are heard in the orchestra. As the steersman, a young Theo Adam (later to become an excellent Wotan and Hans Sachs), warns of the approach of another ship. Jochum now marvelously underscores Kurwenal/Neidlnger’s magnificent death. Ludwig Weber and Ira Malaniuk have their final expressions, all awash with futile despair. And then Jochum and Varnay unite for an overwhelming Liebestod.

These recordings are available from Opera Depot.

![Neidlinger-Gustav-02[Saul-881] Neidlinger-Gustav-02[Saul-881]](https://oberonsglade.blog/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/8de928e61dac39e52f99903868aa90b2.jpg)