What looked quite enticing on paper – a 1963 WALKURE from Stockholm – proved frustrating, not because the performance was sub-par in any way, but because it turned out to be mis-labled and incomplete.

The recording starts mid-way thru Act I. Michael Gielen, a conductor I know little about, has the score well in hand although the orchestra isn’t always up to Wagner’s demands. Arne Tyrén is a less boisterous Hunding than some I have heard, and his voice can take on a wonderfully spooky quality. Birgit Nilsson’s ‘Ho-Jo-To-Ho’ is a marvel, her voice bright and fresh: she makes this daunting opening passage sound easy. Unfortunately, there’s not much more to be said of her performance here, since the Todesverkundigung is ruined by what seems to have been the wayward speed of the source machine used to tape the performance. The pitch rolls up and down with a seasick effect. Then, the third act is missing entirely!

The Wälsung twins are appealingly sung by Aase Nordmo-Lövberg (above) and Kolbjörn Höiseth. Ms. Nordmo-Lövberg, a very fine Elsa in Nicolai Gedda’s only performances of Lohengrin, brings poised lyricism and a fine sense of the words to the role of Sieglinde.

Mr. Höiseth (above) sang briefly at The Met in 1975: he debuted as Froh in RHEINGOLD and repeated that role once; then he stepped in once for an indisposed colleague as Loge and once for an ailing Jon Vickers as Siegmund. I saw him in both the RHEINGOLD roles and he made a favorable impression. Here, as Siegmund, he is a good match for Nordmo-Lövberg – their voices are lyrically compatible. The tenor does experience a couple of random pitch problems, and seems just a shade tired vocally at the end of Act I – understandable, after such a taxing sing. But he makes a good effect in both the Sword Monologue and in the Winterstürme and also in the Act II scene where he attempts to calm to delirious Sieglinde as they flee from her pursuing husband. It’s a pity that the Todesverkundigung is so garbled: I would like to have heard Nilsson and Höiseth in this scene which is my favorite part of the opera.

The mezzo-soprano Kerstin Meyer (above) had a more extensive Met career than her tenor colleague: she sang the Composer in the Met premiere of ARIADNE AUF NAXOS and also appeared as Carmen and Gluck’s Orfeo at the Old House. Here, as Fricka, she is impressive indeed: she begins lyrically – subtle and sure – and soon works herself into a state of righteous indignation. Her victory over Wotan is a triumph of will. Meyer sings quite beautifully, with clear expressiveness.

Beautiful vocalism also marks the Wotan of Sigurd Björling (above). The voice is not stentorian, though he can punch out some impressive notes; the monologue is internalized, sung with a sense of hopelessness that is quite haunting. Despite errant pitch at times, Björling’s performance is moving and makes me truly regret that the third act is missing.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

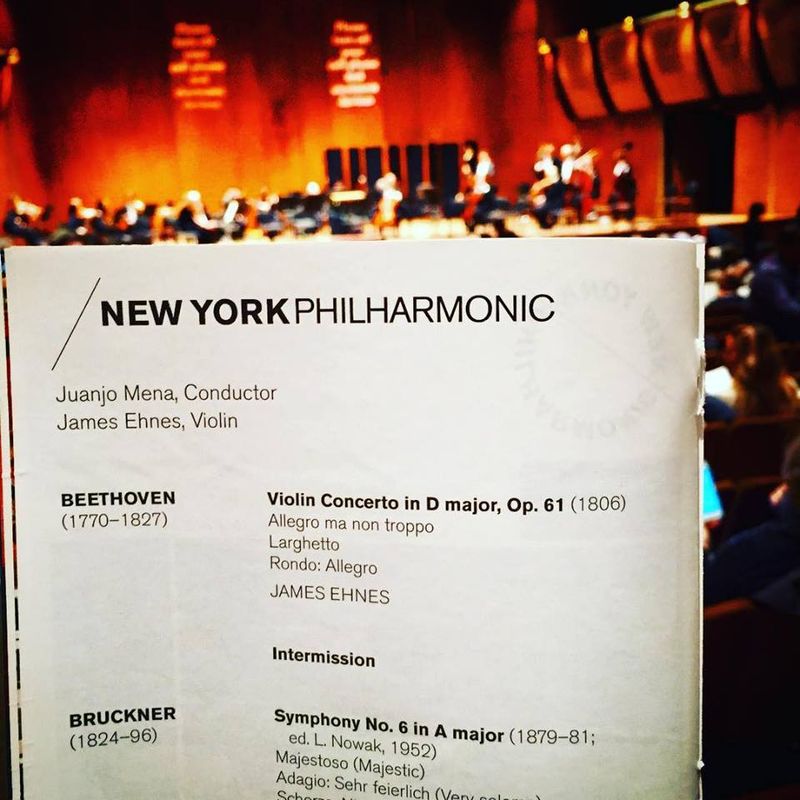

Above: Wolfgang Sawallisch

A tremendous performance of GÖTTERDÄMMERUNG from Munich 1977 gave me a great deal of listening pleasure. I spent several hours with this recording, listening to whole acts repeatedly and zeroing in on favorite scenes to savor the individual characterizations of the very fine cast. Maestro Wolfgang Sawallisch’s shaping of the glorious score had a great deal to do with sustaining the air of excitement around this performance.

This GÖTTERDÄMMERUNG was clearly recorded in-house; the sound of the microphone being fumbled with sometimes intrudes, and there are passages where a singer is too far off-mike to make a vocal impact…and other times when the recordist seems to be sitting literally in the singers’ laps.

The first voice we hear is – incredibly – that of Astrid Varnay; essaying the role of the First Norn, Varnay sounds a bit matronly at times, but she is so authoritative and dramatically alert that it hardly matters. Her diction and word-colourings are endlessly admirable, and her low notes have deep, natural power – most especially on her final “Hinab!” As the Second Norn, Hildegard Hillebrecht is a bit unsettled vocally at times (the role lays low for her). Ruth Falcon’s singing of the Third Norn is more lyrical than some who have essayed the role.

Sawallisch’s forward flow provides a nice build-up to Brunnhilde’s first entry; off-mike at first, it soon becomes evident that Ingrid Bjoner is on peak form for this performance. The voice won’t be to all tastes, but its silvery power, impressive lower range, and sustained phrasing which Bjoner brings forth are thrilling to me, a long-time fan. Jean Cox as Siegfried doesn’t quite equal his 1975 Bayreuth performance of the role, but he’s so sure of himself and has both the heft and the vocal stamina that’s needed. As Sawallisch builds the Dawn Duet with passionate urgency, Bjoner spears a couple of splendid high B-flats before her brightly attacked, sustained climactic high-C.

At the Gibichung Hall we meet the excellent Gunther of Hans Günther Nöcker and the vocally less-impressive but involved Gutrune of Leonore Kirchstein (near the end of the opera, she emits a gruesome scream on discovering the truth about Siegfried’s death). The dominating vocal force of the opera from here on in – along with Bjoner – is the resplendently sung and theatrically vivid Hagen of Karl Ridderbusch. The basso’s rendering of ‘The Watch’ is simply incredible.

Another potent performance is the splendid Waltraute of Ortrun Wenkel, who attained international fame for her remarkable performance as Erda in Pierre Chéreau’s 1976 production of the RING Cycle for Bayreuth which was telecast in its entirety and is preserved on DVD. Wenkel’s abundant tone and vivid sense of the character make her scene with the equally thrilling Bjoner Brunnhilde an outstanding part of this performance. If Waltraute’s parting high-A – always a thorny note for a contralto essaying this role – is cut short, it scarcely distracts from the excitement the Bjoner/Wenkel sister-scene has generated.

Bjoner is staunch in her defense of the ring from the attacking Gunther-Siegfried; abetted by Sawallisch and Mr. Cox, the soprano brings the first act of this performance to an exciting close.

But then things soar even higher, for in an Act II that borders on insanity, the maestro and his cast all seemed to be in the grip of madness. The act begins with the eerie scene where Alberich (creepy singing from Zoltan Kelemen) appears as a vision to the sleeping Hagen. The summoning of the vassals is massively impressive, and later, in the great scene of oath-swearing, Cox and Bjoner blaze away. Throughout the act, the ever-keen Sawallisch guides his forces with a masterful hand. Simply thrilling.

A nicely-blended trio of Rhinemaidens (Lotte Schädle, Marianne Seibel, and Liliana Netschewa) give us a lyrical interlude at the start of Act III: all three vocal parts are clearly distinguishable and they are finely supported by the atmospheric playing of the orchestra, with the horn calls very well-managed. Jean Cox is very much on-mike as he encounters the girls: his big, leathery high-C is sustained…and then he chuckles to himself.

Following Hagen’s betrayal, Cox’s farewell to life and to Brunnhilde is wonderfully supported by Sawallisch: the orchestra playing here is so impressive, the tenderness of the final greeting so lovingly conveyed.

Now Sawallish takes up a deep, glowering rendition of the prelude to the Funeral March; contrasts of weight and colour add to the sonic build-up until the great theme bursts forth in its full-blown grandeur. The spot-on trumpet fanfare and the solid assurance of the horns are a great asset here.

Ridderbusch is terrifying in vocal power and cruelty as he seizes control of the scene, but the raising of the hand of the dead Siegfried when Hagen goes for the ring puts Alberich’s son in his place at last. The cleansing descending scale sets the scene for Brunnhilde, and even though Bjoner is off-mike for the opening of the Immolation Scene, she is vocally unassailable: by “Wie sonne laute…” the mike has found her and she shows both great power and great subtlety in this music. Bjoner’s low notes are vivid, her sustained, lyrical thoughts of the ravens imaginatively expressed, and her noble “Ruhe…ruhe, du Gott!” has a benedictive quality and is very moving. Following her passionate disavowal of the ring, the soprano surges forward with a thrilling greeting of Grane and some exalting top notes to seal her great success in this arduous role. Then Sawallisch and the orchestra bring the opera to a mighty close.

Above: Jean Cox and Ingrid Bjoner