Wednesday May 21, 2014 – Vladimir Jurowski (above, in a Matthias Creutziger photo), who led a series of very impressive performances of Strauss’ DIE FRAU OHNE SCHATTEN at The Met earlier this season, was on the podium at Avery Fisher Hall tonight for his New York Philharmonic debut. The programme featured works by Szymanowski and Prokofiev. In the days just prior to tonight’s concert it was announced that the scheduled violin soloist, Janine Jansen, was indisposed and would be replaced by Nicola Benedetti.

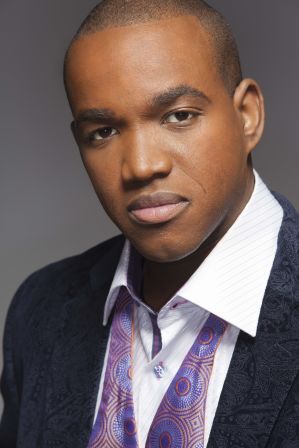

Ms. Benedetti (above) hails from Scotland, of an Italian family. She trained at the Yehudi Menuhin School in Surrey and she maintains a full calendar of orchestra, chamber music, and recital engagements worldwide. A Decca recording artists, Ms. Benedetti takes an active role in music education and outreach. Tall and strikingly attractive, she was welcomed warmly by the NY Phil audience tonight following her excellent playing of the Szymanowski violin concerto #1. This was her Philharmonic subscription debut.

Karol Szymanowski wrote this concerto #1 in 1916. In the course of his musical career, this Ukraine-born but definitively Polish composer progressed from a Late Romantic style of writing thru an embrace of Impressionism (and a flirtation with atonality) to a later period when folk/national music became a strong influence.

Szymanowski’s violin concerto #1, often referred to as the “first modern violin concerto” leaves aside the customary three-movement concerto structure and instead unfolds as a tone poem with the violin ever-prominent. Tonight’s performance was entrancing from start to finish, Ms. Benedetti showing great control in the sustained upper-range motifs that permeate the violin part: here she was able – at need – to draw the tone down to a silken whisper. The composer further calls for some jagged, buzzing effects as well as flights of lyricism from the soloist; a long cadenza requires total technical mastery. Ms. Benedetti delivered all of this with thoroughly poised musicality. Meanwhile the orchestra, under Maestro Jurowski’s baton, paints in a brilliant range of colours, periodically breaking into big melodic themes that have an almost Hollywood feel. Both the piece and tonight’s performance of it were thrilling to experience, and Ms. Benedetti truly merited her solo bow and the enthusiastic acclaim of both the audience and the artists of the Philharmonic.

Following the intermission during which my friend Monica and I were enjoyably chatted up by a young reporter from the Times of London, Maestro Jurowski led a one-hour suite of selections from Prokofiev’s ballet CINDERELLA. This is a ballet I’ve never seen in live performance, though the music’s familiarity comes as no surprise. Tonight’s sonic tapestry of excerpts allowed us to easily follow the narrative, and the Philharmonic musicians gave full glory to the rhapsodic waltzes while individual players took advantage of the ballet’s numerous colorful, characterful solo vignettes. The marvelous, ominous tick-tock leading up to the stroke of midnight and the ensuing mad dash were all terrific fun. The score, full of romance, humour, and irony – and the charming introduction of maracas – provided a superb debut vehicle for Maestro Jurowski. Let’s hope he’ll be back at Avery Fisher Hall soon. And Ms. Benedetti as well.