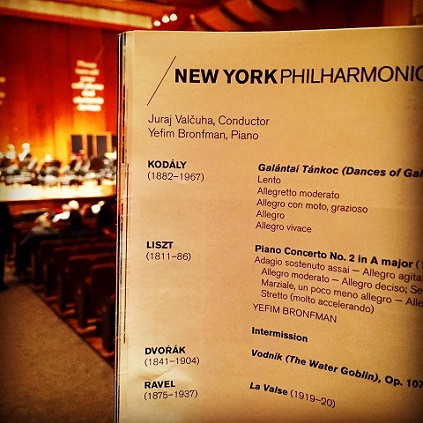

Above: a Met TURANDOT blast-from-the-past with Birgit, Franco (Z, not C), Jimmy, Eva, Liz, and Placi

Saturday January 30th, 2016 matinee – I took a score desk this afternoon to hear the fourth of four sopranos who have sung the role of Turandot during the current Met season. My history of Turandots at The Met goes back to the Old House, where Mary Curtis-Verna was the first soprano I heard in the role. Since then, I have witnessed almost every singer to tackle this part in New York City, from The Big B (Birgit Nilsson) to sopranos you never heard of, several of them at New York City Opera where a perfectly nice Beni Montresor production held forth for many seasons.

At The Met, where Franco Zeffirelli’s extravaganza (which replaced Birgit’s Cecil Beaton setting in 1987) has been home to such post-Birgit divas as Eva Marton, Dame Gwyneth Jones, Ghena Dimitrova, and Jane Eaglen, audiences still cheer – as they did today – the massive vision of the royal palace as it comes into view midway thru Act II.

Act I today was very pleasing to hear: after a dragging tempo for the opening scene of the Mandarin’s address (grandly declaimed by David Crawford, who had the breath control to fill out the slo-mo phrases), conductor Paolo Carignani had everything just about right. The score is a marvel of orchestration: so much detail, so many textured layers of sound. I simply love listening to this music, especially passages like “O taciturna!” where Carignani drew forth such evocative colours from his players.

Anita Hartig sang very attractively as Liu, her voice reminding me just a bit of the wonderful Teresa Zylis-Gara’s. Hartig did not do a lot of piano/pianissimo singing, which can be so very appealing in this music, but she had the power to carry easily over the first act’s concluding ensemble. The Romanian soprano’s concluding B-flat in “Signore ascolta” was first taken in straight tone; she then allowed the vibrato to seep in: quite a lovely moment. Hartig’s voice has an unusual timbre and just a touch of flutter to bring out the vulnerability of the character.

I was likewise very impressed and moved by the singing of Alexander Tsymbalyuk as Timur: mellow and warm of tone, and with a deep sense of humanity.

Whilst not holding a candle to such past Calafs as Corelli, Tucker, McCracken, Domingo, or Pav, Marco Berti did very well in Act I: his idiomatic singing carried well (though Carignani swamped him a couple of times, unnecessarily), and his piano approach to the opening phrases of “Non piangere, Liu” was finely judged. Berti firmly sustained his final call of “Turandot!” at the act’s conclusion.

The three ministers – Dwayne Croft, Tony Stevenson, and Eduardo Valdes – did well, especially as they reminded Berti/Calaf that La vita è così bella! These three singers, as far as I know, sang these trio roles at every performance of TURANDOT this season and made a fine job of it; but a ‘second cast’ might have been given an opportunity. Variety is the spice of operatic life, after all.

After the ridiculously long intermission, Act II started well but then things began to unravel a bit. Mr. Croft experienced some hoarseness, and Mr. Berti didn’t sound solid in the vocally oddly-placed lines at “Figlio del cielo!” where he re-affirms to the old Emperor his desire to play Turandot’s riddle game. A silence of anticipation filled the house just as Nina Stemme was about to commence “In questa reggia“, but the moment was spoilt by voices from the lighting bay at the top of the hall shouting “Have you got her?” The chatter continued through the opening measures of the aria.

Ms. Stemme’s now-prominent vibrato sounded squally at first; the phrasing was uneven and frankly the singing had a rather elderly quality. The top notes were rather cautiously approached and seemed a bit unstable, though she was mostly able to disguise the effort. Concerns about producing the tone seemed infringe on her diction, with some odd results. The opening challenge of the riddle scene – “Straniero! Ascolta!” – did not have the desired ring.

Stemme’s posing of the riddles was a mixed bag vocally – and Berti’s responses were clipped, with traces of hoarseness creeping in. By the third riddle, the soprano seemed to be gaining steadiness. In the great moment after her defeat when Turandot is called upon by Puccini to blaze forth with two high-Cs over the chorus, Stemme made no impact on the first one and was assisted by the chorus soprani for the second. Berti responded with a skin-of-his-teeth high-C on “…ti voglio tutto ardente d’amor!” but the tenor came thru with a pleasingly tender “…all’alba morirò…” before the chorus drew the act to a close.

I debated staying for the third act, mainly to hear Hartig and Tsymbalyuk, but the thought of another 40-minute intermission persuaded me otherwise. Returning home, I found a message from a friend: “So, who was the best of the Met’s four Turandots?” The laurel wreath would go to Lise Lindstrom. Jennifer Wilson in her one Met outing was vocally savvy but it would have been better to have heard her a few years earlier. The role didn’t seem a good fit for Goerke or Stemme, who expended considerable vocal effort to make the music work for them (Goerke more successfully, to my mind) but both would have perhaps been wiser to apply their energy to roles better suited to their gifts (namely, Wagner and Strauss). Still, it was sporting of them to give La Principessa a go.

As with the three earlier TURANDOTs I attended this season, and the many I’ve experienced in this Zeffirelli setting over the years, the house was packed today. Even Family Circle standing room was densely populated. To me, this indicates the opera-going public’s desire for the grand operas to be grandly staged.

There’s a rumor circulating that today’s performance marked the final time this classic production will be seen. It seems a mistake to discard it, since it originated fully-underwritten by Mrs. Donald D. Harrington, revivals have always been generously supported by major Met donors, and it obviously does well at the box office. Why put a cash cow out to pasture? It’s already been suggested that the next Met TURANDOT production will be set in Chinatown in the early 1900s and will star Anna Netrebko and Jonas Kaufmann (who will cancel), with Domingo as Altoum.

Metropolitan Opera House

January 30th, 2016 matinee

Giacomo Puccini's TURANDOT

Turandot................Nina Stemme

Calàf...................Marco Berti

Liù.....................Anita Hartig

Timur...................Alexander Tsymbalyuk

Ping....................Dwayne Croft

Pang....................Tony Stevenson

Pong....................Eduardo Valdes

Emperor Altoum..........Ronald Naldi

Mandarin................David Crawford

Maid....................Anne Nonnemacher

Maid....................Mary Hughes

Prince of Persia........Sasha Semin

Executioner.............Arthur Lazalde

Three Masks: Elliott Reiland, Andrew Robinson, Amir Levy

Temptresses: Jennifer Cadden, Oriada Islami Prifti, Rachel Schuette, Sarah Weber-Gallo

Conductor...............Paolo Carignani

![Lail-Lorri-02[1948] Lail-Lorri-02[1948]](https://oberonsglade.blog/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/7751d6e021a56a6b8ca54744eefdb13e.jpg)